The whole of the chronicle felt barbaric. The lone Bella, throwing herself to death, tired of a life unfulfilled, tired of the brokers and bankers, or of her husband’s trap, his meanness.

Her body died and God had replaced its corpse with the mind of a daughter. God’s delicious invention.

By the hand of his work, he is the creator of life, the mass distributor of poor things. They live inactively in desolation, sleepily marching in some strive for money, power, glory. This lack of autonomy, which envelops God’s work (the animals, the babies), all without independent freedoms.

The progression, then, from child to adult, and the death of curiosity, of self surrender, seems irrevocable. Bella, with the body of the old and the mind of the young, seeks an audacious adventure that can only be marked as premature.

For every one of its unusualness, another facet of its world play tramples it, making each last scene comical in you thinking it strange. Let me think. There was the grinning madman, his abused scalpel, the goose, the maid, and the color yellow. There was the costuming, its theatricality, the length of her hair, the absence of shame for adventure, sex, drama.

The world itself is like Victorian London. It has a flamboyantly sterile air as if everything were made of candy. I’ve tried engrossing myself in the fashion and things, it isn’t timely. It’s a placid reimagining of steampunk, off a place called Wonderland.

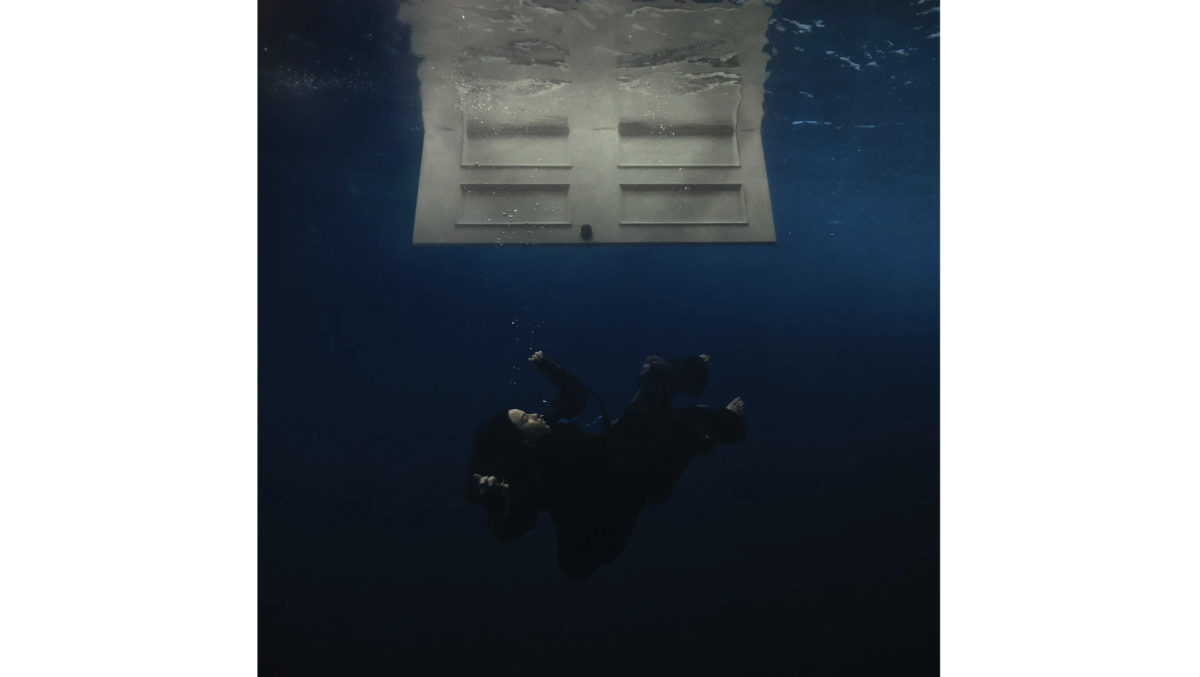

The opening shots are filmed in black and white, muddied through fish eye– it’s lovely. It makes the whole affair seem private, voyeuristic, watching Bella Baxter through a peephole. This lens dramatizes Bella’s singularity, as if a fish out of water. The movie is pretty and subversively imaginative in mirroring a Frankenstein-esque fable, the grossness of detachment from the rest of the world.

Director Yorgos Lanthimos is so wholly estranged from normal. His aesthetics are unruly, unkept. His directorship is done in such a way as to convince and admit his audience to the brutalities of his narrative, the ordinariness of his curious world.

Lanthimos has conjured, now, a brilliant picture profile of unconventionality. I remember having watched his English-language debut film, “The Lobster,” it had cowed me so much. Love as mockery but sustainable to life.

Life, here, is self-indulgence. Plagued with experiment, with deadly sublime. It’s why when Duncan refused her eating another pastry, she’d done it anyway. He had loved his desert just as she did, had the cash and the opportune for another, but, “one is enough.” Bella knows nothing of any limitation.

There’s a precariousness in the youth of a child, free from hurt or danger, absent of money or etiquette. Her sole consummation is to experience the universe, to indulge in it. Is curiosity tethered, only, to the weak and addled minds?

Bella will adventure in finding the becoming world. Swallowing tastes for dance, sadness, literature, the stars, satisfying herself in these things. The lone Bella, throwing herself in felicity, so full of luster, in her pursuit of pleasure.

So, she wakes on a boat, with a man she idly distrusts, with a foolishness so closely imitating infancy. She’s blessed with annoyance and womanhood, neither are taken seriously, and she wants to get off now. (How uneasy she feels above water.) She’s used up Duncan’s money, thrown it to the dead babies on the port and cries and cries.

It’ll be dark soon.

They’re kicked off their cruise and land cold and moneyless in Marseilles, France. The town itself is ugly. It’s grayed and gleaned and frosted all over. It’s a town without pigeons, without warmth and barely with people. And its citizens, as you can imagine, are alike to Duncan, dissatisfied in their want for more paper things.

Her ample youth, the reversion from adult to child, is wicked. In God’s manipulating the two, Bella’s body is abused, unbeknownst to herself, in collecting the sustenance of life. There’s a wild disconnect between her anatomy and her mind, a frail disfiguration that neither takes vanity nor nurture into account. Poor girl, knowing nothing of how the world works. Hungry to consume the niceties of everything.