A portrayal of the wild west matched in its violence only by its historical accuracy, “Blood Meridian: Or The Evening Redness In The West” by Cormac McCarthy is brutal, unsentimental and beautiful. The book has stuck with me perhaps more than any other, images of bloody cowboys around wind-stoked campfires, grand and terrifying massacres, horses traversing volcanic rock, and innocent scalped corpses, surreal and lifelike, burned into my head. Every page of this novel makes me feel like I should never even try to write, because I could never execute anything as well as McCarthy does. Russian writer Vladimir Nabokov is known as ‘The Master’ for his artful and complex prose and his mastery of language, and I think that title could equally apply to McCarthy.

McCarthy’s prose is like nothing I’ve ever read, so incredibly vivid and evocative in its descriptions of death and massacre, of the endless stark landscapes of California, Mexico, and Texas. The writing is intimidating and verbose, but still accessible to a reader who gives it the chance and attention it deserves. It is soaring, inspiring, disgusting, dramatic and intensely real. Unfalteringly creative, it is deeply rewarding in its initial difficulty. With an appreciation of oral storytelling, of the sound of language, the writing is mesmerizing, utilizing the patterns and feel of biblical prose to great effect.

The story presents itself through a protagonist known only as The Kid, a runaway, young, but already possessing “a taste for mindless violence.” After a short stint in jail in Chihuahua City, Mexico, The Kid falls in with a gang of scalp hunters, mercenaries paid for each Native American scalp they return to whoever has hired them. The Glanton Gang, based directly on real historical figures, includes, among other unsavory figures, captain Joel Glanton, a variety of criminals with names like Bathcat and Toadvine, an ex-priest, two men named John Jackson (doomed to fight to the death, according to others in the group), The Kid, and one of the best literary antagonists of all time, Judge Holden. The plot follows their meandering, dangerous and hedonistic path of destruction across Mexico, Texas and California, as well as their eventual collapse, and the continued life of The Kid, identified in the book’s later chapters as ‘the man.’

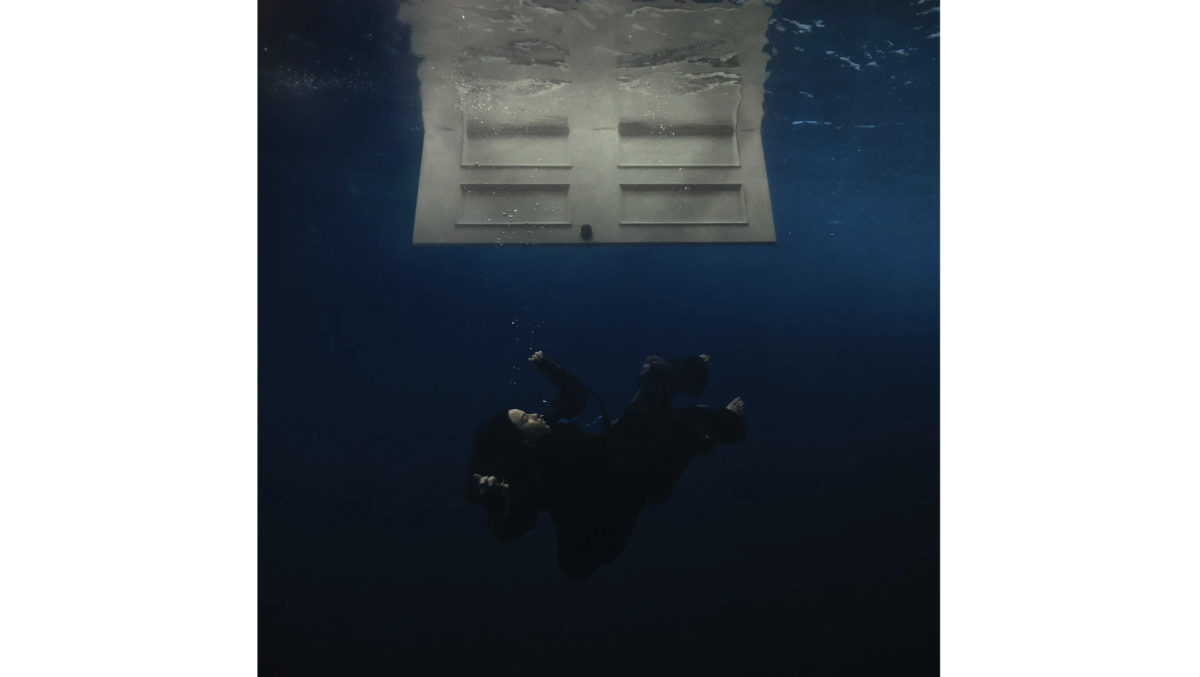

The novel’s reputation as unadaptable to the screen despite its prestige is often attributed to its extreme violence. Brilliant and graphic, McCarthy depicts so much that could never be shown in live action, going where most writers wouldn’t dare.

Returning to the antagonist of the story, Judge Holden is completely hairless, of inhuman strength and size, perfectly dressed, and incredibly intelligent. He is a character of extreme power, with a horrifying worldview of philosophically justified brutality, molestation and violence. Infanticide, torture, massacre of innocents, sexual abuse, The Judge is remorseless. “Whatever exists without my knowledge, exists without my consent,” he explains, in one of his many fireside sermons to the gang. His desire to master the world, to assert his will, is boundless. The Judge worships war, and finds a sick morality in his theory of it.

“It makes no difference what men think of war… war endures. As well, ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way,” The Judge says, arguing with the ex-priest, commenting that “Men of war and men of god have strange affinities.”

To the Judge, “Moral law is an invention of mankind for the disenfranchisement of the powerful in favor of the weak;” any idea of morality irrelevant in the all encompassing game of combat. Fascinating and morbidly compelling, the Judge and his relationship with The Kid could be analyzed endlessly in search of a message about mankind’s affinity for violence, war as a historical force, and whether our darkest impulses as a species will win out in the end. “Blood Meridian,” full of evil actions, gives little or arguably nothing in regards to an answer about the moral state of humanity, or about morality at all.

In an incredible lecture on the novel, Dr. Amy Hungerford analyzes the ways in which the novel asserts itself as a significant literary statement, breaking down the barriers between history and fiction, between inspiration and originality, between good and evil. “McCarthy’s novel does not fail in making us see war as evil, because we’re confronted over and over again with these scenes of violence, over and over again with its gratuitous nature,” says Hungerford. However, she continues, “It does not count war an evil because it has not allowed a moral machinery to have a place in this universe, or in the logic of the novel.”

She connects the work to Moby Dick, the Judge to Captain Ahab, as well as to Paradise Lost, the Judge as Satan himself. Finding overt allusions or inspirations in Blood Meridian doesn’t require any reaching. As McCarthy himself stated, “The ugly fact is books are made out of books, the novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.”

Blood Meridian is a difficult novel, one that many readers may start and not complete, may put down, horrified, haunted, or just uninterested and frustrated. But the very things that make the novel difficult are also what makes it so uniquely impactful, what makes it so fully worthwhile. So if you try this book, and I highly encourage you to, and you want to put it down, I implore you to keep reading, to give it a chance, to pause, but always to return.