“Nothing will come of nothing:” A Succession Retrospective [SPOILERS]

The latest installment in a prestigious list of critically acclaimed HBO television series, “Succession,” broadcast its series finale Sunday night, debuting at a 9.6/10 stars on IMDb, 2.9 million viewers and endless online buzz. Praised for its standout acting performances, straight-faced satirical humor and fast-paced dialogue steeped in literary references, the family dynasty drama had a few, pun intended, successes.

I found its aforementioned humor to be the perfect pace of stilted corporate-speak exploding into chaos. The excitement of crowding around the television on weekend nights, Twitter feed in hand, was something I had missed since the end of Euphoria Sundays. Ultimately, it succeeded in being a show that, week after week, I found myself sitting down for.

Plenty of words have been written on how great Succession is, and rightly so.

The failures of Succession, particularly in its final season, are exhaustingly obvious. Succession feels like the pinnacle of ‘made by committee,’ unsure of exactly what it wants to say. Initially marketed as a dark satire heavily inspired by—nearing biographical territory of—media empire family the Murdochs, the narrative quickly veered into being a deeply empathetic character study of those born into wealth. Aside from the cardinal sin of inspiring countless NYT op-eds, Succession feels unaware of how to strike this balance. It doesn’t dare critique the Roys, corporate America or capitalism; it vaguely gestures at the cyclical nature of money and power. Its efforts to humanize the Roy siblings feel overindulgent for me, only working with characters like Tom and Greg and Gerri. Throughout all four of its seasons, it continually introduces sprawling b-plots only meant to leave some sort of emotional impact on its protagonists, whose lives and perspectives and personalities are shaped in no meaningful way.

Take, for example, the penultimate episode of the show. It concludes with a shot of Roman, distraught after his father’s funeral, walking into a crowd of protesters and trying to pick a fight. The show introduces this entire increasingly urgent subplot about a violent nationwide outcry after American Television Network’s (ATN) contested declaration that alt-right candidate Jeryd Mencken is the president elect, which ultimately is used in no way other than to provide this rather goofy emotional catharsis for one of the show’s main characters. If you’re going to introduce entire meandering plot threads for the sole purpose of impacting the characters, then please, let the characters be impacted. The show insists on everyone’s one-notedness far too much. A similar pattern is used for Kendall and his inability to grapple with his own responsibility towards the death of a young waiter in the finale of S1, for Shiv and Tom’s forever spiraling relationship and, of course, the show’s guiding question of who will succeed Logan Roy.

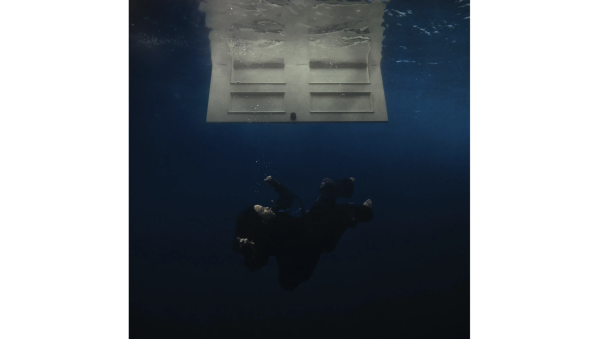

Throughout its full 39 episodes, the stakes are ever-increasingly raised, yet no consequences are ever felt. The show’s finale concludes with all siblings essentially the same as when they began, unable to put aside their ambitions for their family, even when presented with an assured opportunity to do so and succeed. As viewers saw about an hour into the finale, Shiv decides to vote to not reject the GoJo deal, not simply because she genuinely believes that Kendall will be a bad CEO or is against the best interests of the company, but because she is jealous and cannot crawl out of the crater of ambition that festers inside her gut. She is jealous, and the trio cannot escape the same fate as they revert to angry toddlers and slap and grab and yell at each other.

Part of the reason that the emotional journey (or lack thereof) of the characters falls flat for me is how shockingly vile they consistently are. In the aforementioned scene of S4E9, as emotional music fades in, the camera lingers on a man collapsed and sobbing, except that that man is an ultra-wealthy perverted Nazi-sympathizer. The ‘babygirlification’ of the Roy siblings and overabundance of pretentious thought-pieces online is a clear testament to the empathetic portrayal of each character. As S4E8 and E9 seem to suggest, “Succession” is a show about people who are destructive and repulsive and deeply complicated and worthy of our empathy, yet by the end of it, all I can only feel bored of them. I feel I’ve been given no reason to care if the ultra-wealthy, perverted Nazi-sympathizer is sad or not.

This could all be forgiven by me if the show had some grand message about the cycles of wealth and power. This seems to be what the finale insists upon, with callbacks to the opening credits in its cinematography and clear parallels between Tom and Logan and Shiv and her mother respectively. But if the point of the show was to be the rather milquetoast message that power is cyclical and won’t make you happy, it should’ve been one season. Four seasons that beg the viewers to empathize with characters who are truly put through everything—death, abandonment, physical abuse, emotional abuse, a funeral, divorce and of course, family infighting—feels like far too much to simply be capped off with an unimaginative commentary on how nothing begets nothing. It also fails in its satirical efforts, as throughout the fourth season (and especially in the finale) it is so abundantly self-serious in its directorial and cinematographic efforts one could only imagine it as some sort of meta-satire of television shows satirizing the rich.

I found the finale similarly saccharine. It donated far too much of its already near 90-minute runtime to scenes of the siblings crying happy tears and hugging and playing. It feels rushed when, only a scene or so later, the three immediately turn on each other again in the name of what, mutually assured destruction?

They got so lost in making an ‘HBO Drama’ that they abandoned all other aspirations. It flirts with the idea of satire, of family drama, of corporate drama, of critique and of an overly earnest story about generational trauma. Perhaps it could have been all of these in depth. Ultimately, after the credits rolled for the final time, I couldn’t help but think about all that “Succession” could have been.