Oh Bother! “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey” Offers a Lesson in Freedom of Expression within the Public Domain [Spoilers]

“This ain’t no bedtime story.”

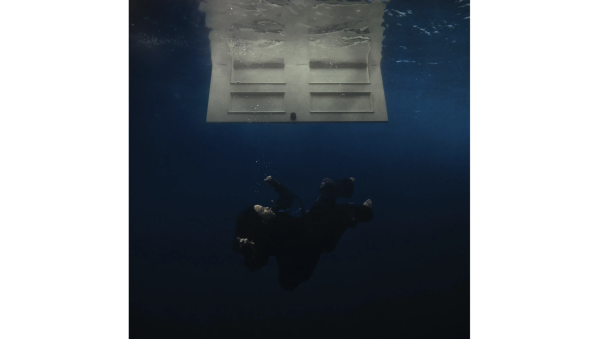

This tagline was plastered on thousands of movie posters promoting director Rhys Frake-Waterfield’s “Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey.” Author A. A. Milne’s beloved characters undergo a drastic makeover as they are transformed into feral serial killers who prey upon the residents of the Hundred-Acre Woods. Prior to its release Feb. 15, the art community was abuzz with curiosity and anticipation for what will come as more popular works enter the public domain.

For 95 years, the A. A. Milne Estate owned the copyright for the original “Winnie-the-Pooh” children’s book, making it intellectual property. If a creator wanted to produce a work based on Milne’s characters, they had to request permission and pay a fee to the estate, or Disney, who bought the licensing rights in 1961. Caitlin Carlson, professor and chair of the communication and media department at Seattle University, details how these laws serve as a way to protect the original creator’s work and provide royalties for themselves and devisees.

“Intellectual property laws, like copyright, allow creators to determine how their work is used,” Carlson wrote to The Spectator. “Oftentimes, these creations can generate profits for organizations when they are featured in books, television and films. Owning the copyright gives the copyright holder the discretion to determine when and where the work is used.”

After the copyright ended in 2022, “Winnie-the-Pooh” entered the public domain, allowing creators to produce works based on Milne’s characters freely. While it is impossible to determine how Milne would feel about Frake-Waterfield’s film, Magaret Chon, the Donald and Lynda Horowitz Endowed Chair for the Pursuit of Justice in the Seattle U School of Law, believes creators should be given the opportunity to produce work based on popular media. Through the public domain, Chon says individuals can capitalize on works that were once out of reach to them because of copyright laws.

“The public domain provides a lot of raw material for making money. It is not just Hollywood studios who can take [creative work] and do something with it,” Chon said. “I think that is really important to allow that freedom for the rest of society to create stuff.”

One student who sees the public domain’s benefits is Second-year Chemistry Major Neve Quinn. In their spare time, Quinn writes science fiction stories that they only share with close friends. Although they see writing as a hobby rather than a profitable activity, Quinn believes creators should be able to write stories based on others’ work without having a price attached.

“I think [the public domain] promotes creativity because there are a lot of ideas out there that can be used again and again, and I don’t think it is necessarily ‘stealing work’ as it is building off an idea. I think two ideas can exist [without] it being [considered] stealing,” Quinn said. “It’s weird that people are putting money and barriers up to people’s creativity [despite it being] an escape for people [who]are consuming [and] producing the work.”

With a reported $100,000 budget, Drake-Waterfield’s horror film has exceeded that amount in the box office, totaling to around $1.7 million domestically and counting. Despite its success, it has been panned by critics for its clichè narratives and low production quality. Some audience members believed the film was a hilariously entertaining spin-off of the original children’s book, despite it receiving a 4/10 user rating on IMDb.

Both reviews have merit, as “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey” could not settle on whether it wanted to be a serious horror film or a satiric take on A. A. Milne’s original characters. Because of the lack of identity, the film seemed incomplete as many characters and stories were not expanded on enough. There was no attempt at making any of the characters intriguing or sympathetic, reducing them to items on Pooh and Piglet’s chopping block. It seems this movie’s existence was to flaunt the “Winnie-the-Pooh’” image without creating an original story.

Clodagh Walsh, as second-year psychology major at Seattle U, watched “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey” and expressed their dislike for the film’s writing, characters and plot.

“It felt like whoever wrote this movie sat down and wrote some creepy Winnie the Pooh fanfiction. [But] it’s been like 100 years; what does it matter?,” Walsh said.

Frake-Waterfield has confirmed a sequel is in the works with an expected February 2024 release date, according to Variety. With the hopes of earning a higher production budget, viewers may have to take another trip to the Hundred-Acre Woods to truly see Frake-Waterfield’s vision.