Early each morning, a man wakes up, sits in a chair in his bedroom, sips a cup of coffee and reads a sampling of poetry for 15 minutes. He then walks out of the Arrupe House along the upper mall of campus and begins his day as the highest appointed official at Seattle University.

President Fr. Stephen Sundborg, S.J., says he is “married to poetry.” He didn’t begin courting her until 11 years ago, when he first began reading it. Now, he says, he’s “faithful to her,” and can’t imagine life without her.

“I’m a priest,” he said. “And I have a conviction that poetry is the twin of prayer.”

To him, prayer is about placing oneself in the presence of an unseen God.

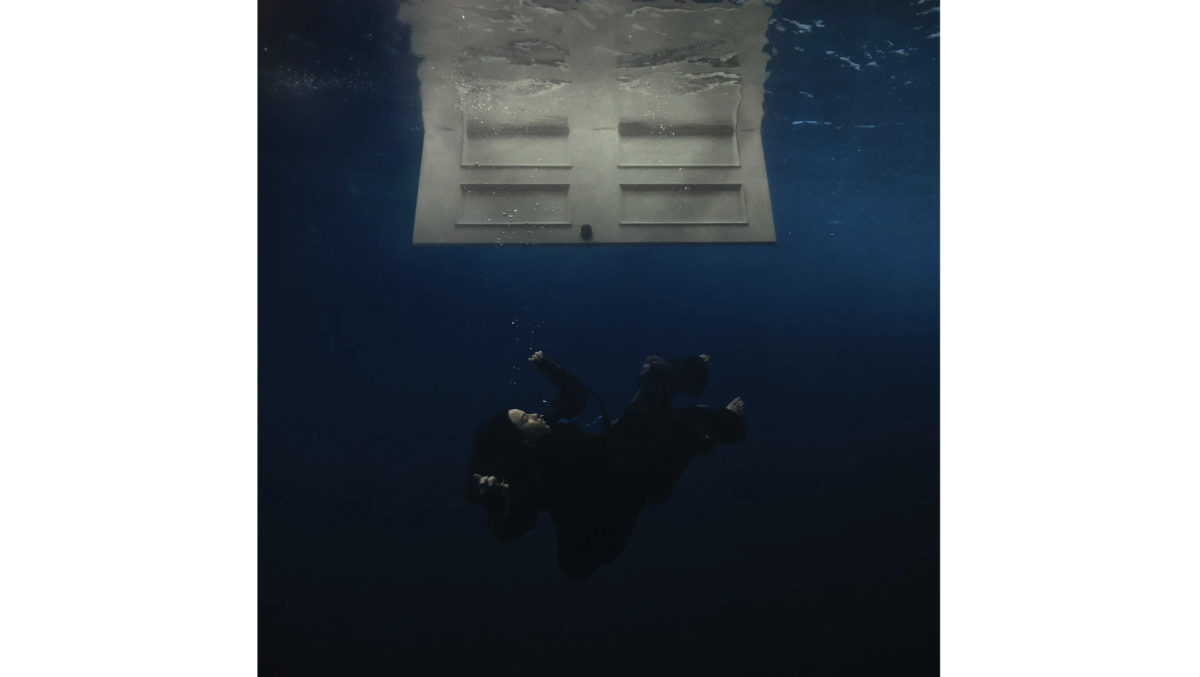

“Poetry is putting yourself in the presence of things that are beneath the surface of what life is,” he said. “Its deeper richness.”

He described finding poetry as a revelatory experience.

“It’s like discovering a food that you didn’t know you liked and you find out it’s delicious,” he said.

Fr. Sundborg is most drawn to the “selected works” of a poet, which he says create a chronological, autobiographical presentation of their work and, ultimately, of their life, by revealing things about their childhood, loves, marriages, engagements and sexuality.

The president has no interest in writing poems, but enjoys reading contemporary poetry from the last 75 years there is accessible and isn’t jumbled into what he describes as a “jigsaw puzzle” of literary devices.

Some of his favorite poets are Mary Oliver, Billy Collins, Mary Stewart Hammond, Philip Larkin and Seattle University professors Sam Green and Sharon Cumberland.

He explained that oftentimes, in everyday life, there is more going on beneath the surface than the reality of what the physical world presents.

“All of us, at any time, are not fully aware of the deeper dimensions of what our experience is,” he said. “And what poetry does, it gets underneath the soil of life and it gets down to the more tender tentacles or roots of the plant of life.”

He recited a poem called “Entering History” by Mary Stewart Hammond. “There’s dimensions of myself that I cannot express for myself that [her poem] will express for me,” he said. While he speaks about poetry, it appears as if the president is in a daydream in a far-off land. Perhaps he’s in the Umbrian countryside of Hammond’s poem. Maybe he’s wandering back to fond childhood memories. But it is clear that the written art form has a captivating power over him.

ENTERING HISTORY by Mary Stewart Hammond

The door to the poem opens in, and a couple enter,

set down their luggage, and stand, backs to the door,

silhouetted against the light, taking in the room.

They step through French doors in the far wall

onto a balcony cantilevered over ramparts, and the vast

impastoed Umbrian kingdom swoops away

and down. They have climbed this world in first

and second gear, half the afternoon, past 12th century belfries

and 500-year-old cypresses, up the very blacktop

switchbacking through the view. Dirt roads lead off it,

wandering Etruscan boundaries to invisible purpose.

An ancient farm truck, no bigger than a pencil eraser,

and the only sign of life and the 21st century, crawls,

without a sound, along one of them. On distant hills,

the honey and terra cotta of Assisi, Spello, Spoleto,

hover in the haze like cities of God fallen to earth,

for the habitation of humans the size of seeds

on white-haired dandelions. She leans her head on his shoulder.

He kisses her. They’ve already shrunk half an inch

since they began their lives together. They turn,

reenter the room, cross back and forth in profile, unpacking.

He’s acquired a stomach, and his hair has gone white.

She pulls off her clothes. There is a scar on her breast,

one in her armpit; three more run like roads

across and down her belly. A bloom of spider veins

tattoos her calf. They’re getting old, but not so old

we shouldn’t close the door on their nap.

Tonight they’ll have dinner downstairs.

Tomorrow they’ll drive off into the view. For now,

they’ll awaken in this minor city of God

entwined in each other’s arms. We’ll hear them talking,

sotto voce on the other side of the poem,

dusk erasing their bodies.

He called Mary Stewart Hammond “exquisite,” adding that in reading her selected poems, “I’m reading the biography of her heart.”

About 25 minutes into the interview, his secretary knocks and says someone of great importance is on the phone.

“Could you arrange a time for me to talk with them some other time?” he asks the secretary.

The conversation resumes, as does the trance-like expression in his voice. Poetry soothes him, and it appears as if the discussion of it does, too.

Fr. Sundborg said he works 60 to 70 hours a week and the “topsoil,” or surface level, of his life is rather rigid.

“And poetry gets underneath it,” he said. “Under the texture of what life is like, underneath all that hardness, and it sort of loosens the ground there.”

He says he is faithful not just to poetry, but also to his poets; he only reads one poet at a time, their entire selected works, over the course of six or so weeks. He added that he’d much rather read 100 poems written by one poet than one poem from 100 different poets.

He says his reading of poetry affects the way he carries himself and ultimately, his leadership style. He described himself as a reader and says every leader ought to be one because reading informs, takes us places and keeps us alive mentally.

“It’s not just the poetry of the 15 minutes,” he said. “But it loosens the ground of yourself.”

The president keeps a notepad of paper documenting every book he’s read as president of Seattle University for the last 20 years. “There’s 67 pages of the books that I’ve read.” He estimates he’s read about 670 books in the last two decades, many of which are poems.

“So I become like a friend [to the poet], and the person becomes like a friend to me,” he said. “And that sort of softens my life.”

Tess may be reached at

[email protected]