Changes to Student Handbook Language Sparks Dialogue About Students’ Right to Protest

Left: The October 14th, 2019 Planned Parenthood protest. (Javier Plascencia). Right: Image of the main floor of the Casey Building during the Matteo Ricci protests which occurred between May 11 and June 3 of 2016. (Kyle Kotani).

As a university that prides itself on its commitment to social justice, promoting a vision to be “one of the most innovative and progressive Jesuit and Catholic universities in the world,” Seattle University professes support for political action at a foundational level.

While promoting social activism, Seattle U outlines parameters within which demonstrations and political activities on campus may take place.

In the 2022-2023 Student Handbook, the university acknowledges the right of Seattle U students to utilize free speech and express their opinions regarding political and social ongoings. This acknowledgment is made in tandem with an expressed duty to protect regular university functions.

Seattle U’s public proclamations withstanding, some students do not feel that Seattle U’s written values align with their reactions to public demonstrations and political action on campus.

Natalie Kenoyer, a fourth-year history and political science double major and president of the Young Democrats of Seattle U, finds the university’s policies against advocating or promoting individual political candidates restrictive.

“We can’t endorse candidates as a chapter based on campus, so we can’t leverage that reciprocal power relationship that could bring candidates and elected officials to Seattle U to talk with students and get them connected to jobs and other opportunities,” Kenoyer stated.

The university does allow for issue-based protests, so long as it does not interfere with an “atmosphere conducive to academic work.”

A new proposal to the Student Handbook, however, outlines that “Infringement upon the academic freedom of others, or the disruption of university operations, programs, events, or activities” is a violation of university policy. Similar language is proposed in the Faculty Handbook.

Anton Ward-Zanotto, assistant dean of students and director of integrity formation at Seattle U, stated that while the Student Handbook has long contained a policy regarding students’ right to organize and protest, the proposal seeks to solidify university expectations.

“In the new version of the code, the language around disruption is intentionally designed to prompt discussion about what the norms for campus and classroom discourse are and help our community as they engage with each other around challenging topics,” Ward-Zanotto said.

Seattle U has a longstanding history of on-campus demonstrations in response to political issues, from the Matteo Ricci sit-in of 2016, which was in response to a lack of diversity in the college’s curriculum, to the Planned Parenthood protests of 2019, which addressed former President Fr. Stephen V. Sundborg, S.J.’s decision to remove the organization from the College of Arts and Sciences recommended resources page.

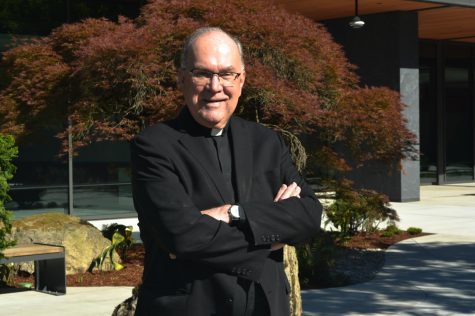

When asked whether or not this new language was proposed to prohibit similar demonstrations or unionization attempts, Eduardo Peñalver, president of Seattle U, expressed in a written statement to The Spectator last week that this was not the proposal’s intention on either the student or faculty level.

“This policy makes clear that freedom of speech on campus does not include the right to prevent others from speaking. Disrupting a campus event because of disagreement with the speaker or interfering with classroom instruction infringes on the free speech rights and academic freedom of the person who is silenced as well as the rights of those who would like to hear what the speaker has to say,” Peñalver wrote.

Students like Kenoyer, however, remain wary that the new language will impede their freedom of speech.

“This policy can and will be used to punish student activists for engaging in social justice issues and directly interferes with our free speech rights. Student protests are a vital part of the educational experience on campus and can help open up a productive class dialogue about important current events,” Kenoyer said.

The new proposed language has been agreed upon by a committee of student representatives from the Student Government of Seattle U, the Graduate Student Council, the Student Bar Association, a faculty representative from the Faculty Assembly and staff representatives from the Staff Council as well as from within the Division of Student Development.

“[We] integrated almost all of the feedback we received in a way that our students, faculty and staff on the committee felt good about,” Ward-Zanotto stated.

While Ward-Zanotto and Peñalver expressed their support for the new language and their belief that it will assure the rights of students, some students are hesitant to agree.

“I think the school does a lot of talk about social justice but does a lot of disempowerment of student activists under the table,” Kenoyer stated.

As the university goes forward with the updated Student Handbook, responses are varied. Administration supports the new language, hoping it will foster an environment that facilitates learning. On the other hand, student activists are apprehensive about its effects and how it will impact protests and demonstrations in the future.