Community Within Culture: PeaceTrees Vietnam and VSA [Guest Opinion]

This winter quarter, as seniors pursuing our communications major, we are required to complete a course called Practical Experience. For this class, we are expected to draft and execute a quarter long communications plan for local organizations around Seattle.

Our group was presented with the opportunity to intern for PeaceTrees Vietnam, an organization that works to clear landmines and unexploded ordnance in Vietnam, as well as to support local communities in developing sustainable economic and educational opportunities.

Children and families in central Vietnam continue to face grave threats to their lives and way of life as a result of the terrible effects of the Vietnam War. Southeast Asia was the scene of the protracted Vietnam War. It started in 1954, with the division of Vietnam into North Vietnam and South Vietnam. North Vietnam desired a reunification of the nation under the political and economic principles of Communism.

In an effort to prevent this, South Vietnam fought. Despite the United States assistance to South Vietnam, North Vietnam was able to win the war in 1975. Vietnam became a cohesive, communist nation soon after. The aftermath of the war was devastating, huge numbers of lives were lost during the Vietnam War. Almost 1.3 million Vietnamese soldiers as well as about 58,000 American soldiers perished. Also, more than 2 million citizens who weren’t involved in the battle also died amongst the chaos.

Jerilyn Brusseau, the founder of PeaceTrees Vietnam, has reckoned with the devastation of the Vietnam War.

“My younger brother Daniel Cheney was an assault helicopter pilot and he was shot down and killed on his 16th day in Vietnam,” Brusseau said. “Dan saved the life of the pilot just ahead of him and in so doing, Dan and his co-pilot were killed.”

It was 1969 when Brusseau learned of her brother’s death. As Brusseau mourned him and imagined the loss that her parents must have also been feeling, she came to a realization.

“This big light came on,” Brusseau said. “There’s thousands and thousands of people like my parents losing their kids, uncles, dads and brothers in this war…The Vietnamese are losing thousands and thousands of family members.”

It would not be until 1995 when the idea for PeaceTrees was born. Then-president Bill Clinton announced the normalization of diplomacy between the U.S. and Vietnam.

“Something in my mind came to me and said ‘someday, somehow, some way, we must reach out to the Vietnamese people to honor their losses as well as our own and begin building bridges of trust, understanding, and friendship,” Brusseau said.

It was later that same year when Brusseau and her husband, Danaan Parry, a nuclear physicist who held a deep passion for clearing leftover war ordnance, gathered a small team of friends with American war veterans to develop the plan for PeaceTrees.

The team were officially welcomed to Hanoi, the Vietnam capital, to meet with Vietnamese leaders from the People’s Committee and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“It’s time to close the past and open the future,” one of the leaders said to Brusseau.

Brusseau’s team were immediately invited to Quang Tri province, considered the most war-torn province in Vietnam.

By continuing to clear the destruction the Vietnam War left in its wake and planting trees, PeaceTrees assists the Vietnamese people to reclaim land free of landmines, promoting healing on both ends.

PeaceTrees was the first American organization allowed to support humanitarian demining operations. PeaceTrees’ work is still firmly grounded in a long-term dedication to fostering kinship and understanding between both American and Vietnamese citizens. The world looks to PeaceTrees as a beautiful example of how tragedy and conflict can be turned into peace and cooperation.

Unfortunately, as time has progressed and the impact of the Vietnam War on the U.S. became less and less damaging, this catastrophic event has become irrelevant to today’s generations. Despite its importance in the past, the Vietnam War is no longer considered a major factor in U.S. culture and politics.

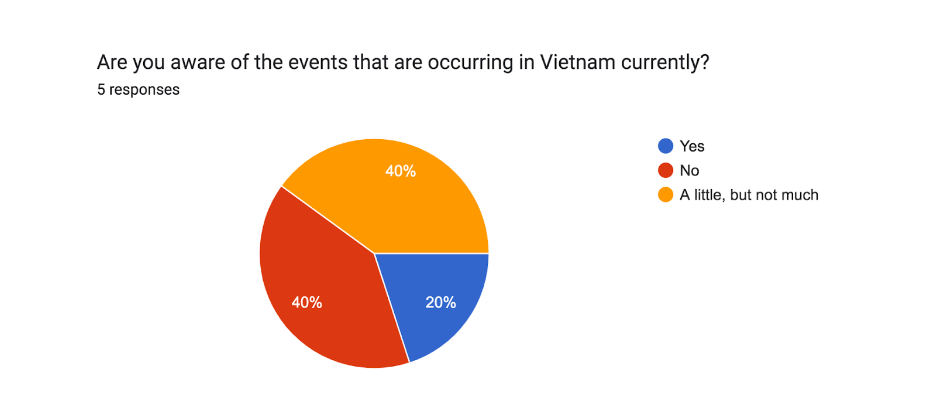

As a result, younger generations have been left with little to no understanding of the war and its significance in history. As a group, we wanted to explore this idea further by trying to understand where the cultural disconnect occurred within our up and coming generation and how we could potentially bring awareness to the impacts of the legacy of war in Vietnam to the issues that are still plaguing Vietnam.

A big goal of PeaceTrees was to be able to work and bridge a relationship with Seattle U’s Vietnamese Student Association. VSA is a cultural and community based organization here at SU, located on most college campuses, who strives to create a community of students that can uplift, support, and understand one another.

Despite it being centered around Vietnamese culture and history, students from different cultural backgrounds are all welcomed. The goal of this group is to create an enduring Vietnamese community on campus by promoting, preserving, and educating students about Vietnamese culture.

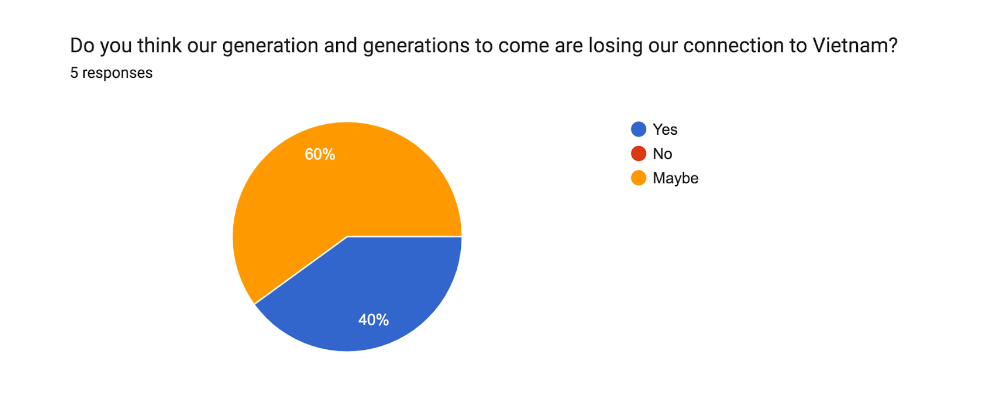

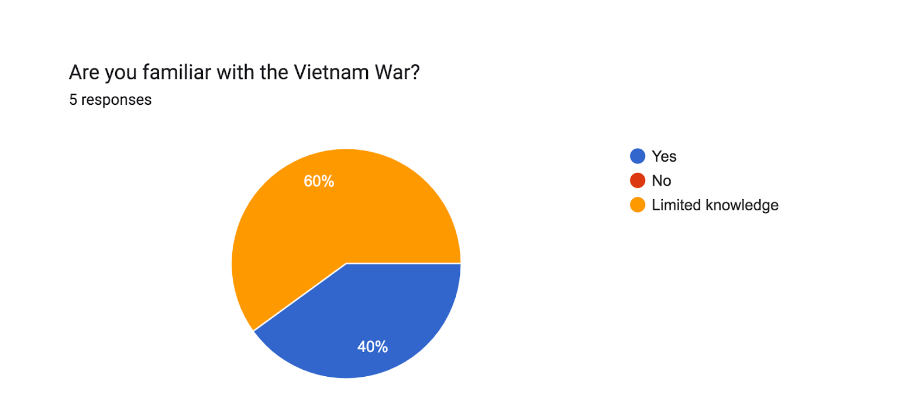

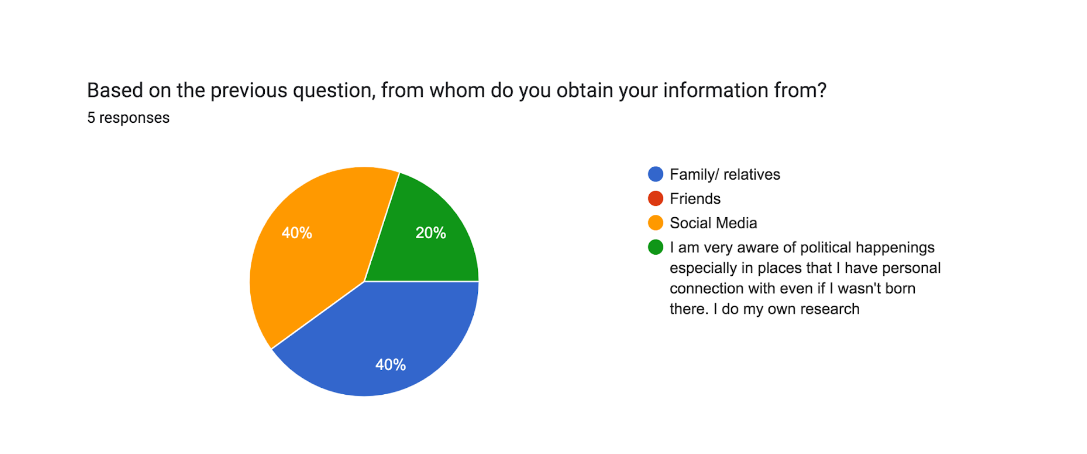

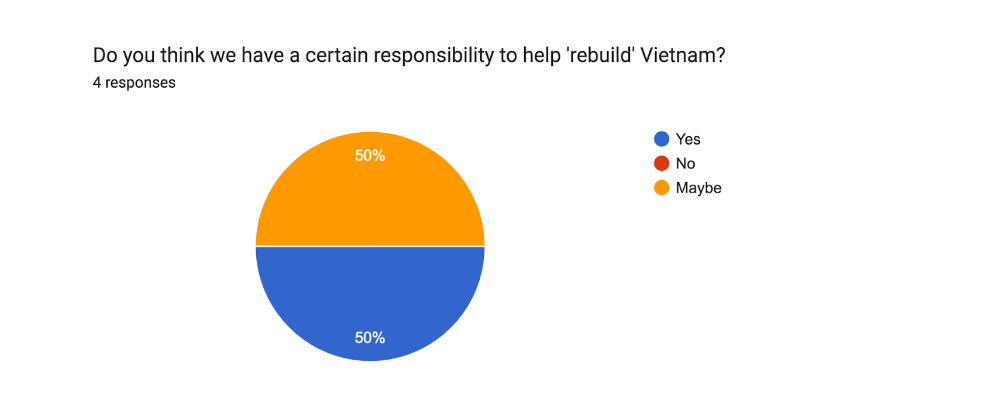

We wanted to be able to engage in conversation with VSA about their knowledge and experience regarding the Vietnam War and their own cultural background. A Google Form was sent out to members of the group asking a series of questions ranging from “Do you feel connected to your Vietnamese culture/background?” to “What are some things that you think we can do to better support Vietnam?”

We received a variety of insightful responses and due to the personal aspect of each response, the responses that we included within the article, the individuals will remain anonymous. This was done to ensure that all respondents felt comfortable sharing their honest thoughts and opinions without fear of being judged or identified. Maintaining anonymity allowed for the honest exchange of ideas and opinions.

Our overall findings based on this Google Form combined with prior knowledge of how our generations interact with historic events is that we’re in the midst of having knowledge of what has occurred, but not feeling that relation or connectivity.

Our generation prides itself on being progressive and open-minded to be able to learn new things, but some can tend to lose touch with their culture while doing so. You can travel one of three ways in life: either forward motion, circling in place, or moving backwards.

Simply put, you’re constantly adjusting to what is ahead. Some argue that adhering to the same traditions and outdated ideas will prevent you from moving forward in life. The culture you are most familiar with may become less relevant to your own circumstances and interests.

While the conversation of adapting and adjusting rings true, there’s a sense of comfort in having cultural traditions to come back to and knowing you’ll always have a community. Different cultures provide us with a more comprehensive understanding of the world by offering up a multitude of perspectives, knowledge, and values.

Having our own distinct cultural identity and being able to share that with others is how community bonding begins, relationships are built, and how problems can be effectively resolved through this collaborative system.

A culture starts to develop any time a group of individuals band together to work toward a common goal. There are beliefs, norms, values, and behaviors that evolve in groups of any size. While VSA works to preserve culture and build community, PeaceTrees focuses on building bridges of trust and understanding between Vietnamese and American citizens alike and educating people on the long-lasting effects of war to ensure that history isn’t lost or forgotten, but instead passed on and celebrated.

These organizations provide a platform for individuals to share their stories and experiences, which helps to create a sense of community and mutual understanding. This allows for the preservation of cultural identity and heritage, as well as the development of new values, beliefs, and behaviors.