Tate’s Technological Trickery

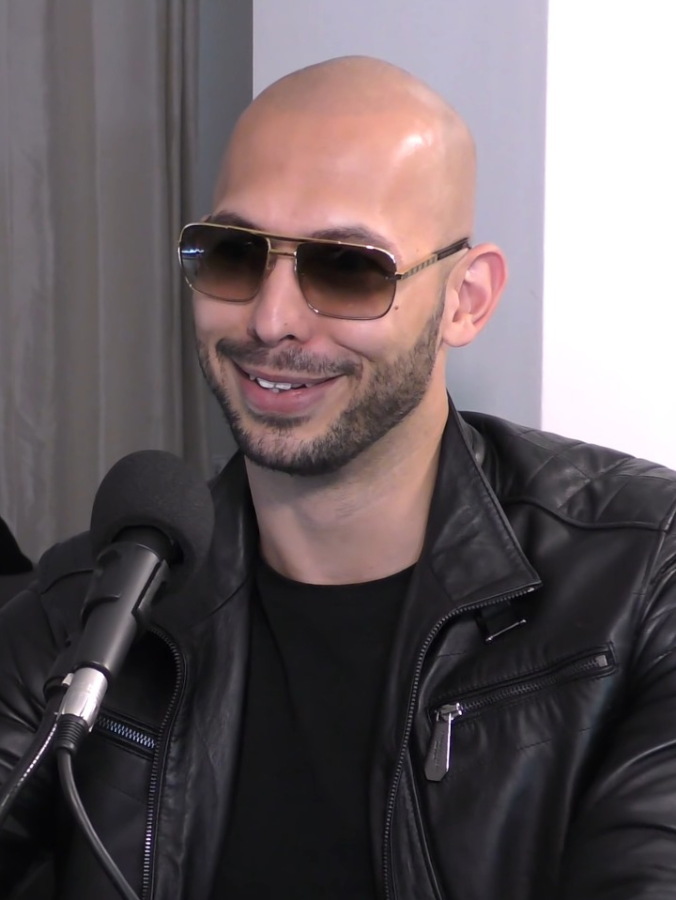

Andrew Tate, a social media personality who gained traction for self-described misogynistic remarks, was arrested alongside his brother Tristan in Romania on charges of human trafficking, organized crime and sexual assault. Months before his arrest, Tate was banned from major social media platforms Instagram and TikTok for violating hate speech policies, where he had amassed a follower count of over five million collectively.

Despite the ban, Tate’s presence online remains in a number of forms. This is particularly alarming to Joanna Schroeder, a feminist writer and mother of a child who was exposed to alt-right social media content promoting misogyny, white supremacy and Holocaust denialism. Schroeder discovered an initial pipeline to white supremacy implemented to keep viewers engaged, similar to any other trend on social media. Schroeder says social media algorithms play a critical role in leading young adolescent males to accounts featuring extremist right-wing content.

“Social media and vloggers are actively laying the groundwork in white teens to turn them into alt-right/white supremacists, it’s a system I believe is purposefully created to disillusion white boys away from progressive/liberal perspectives,” Schroeder said in an interview with NPR.

Mark Cohan, an associate professor of sociology at Seattle University and a gender scholar, inspects masculinity and its relationship to manhood. Cohan believes that examining gender socialization as a power structure and how it has been maintained in cultures across society is one way to significantly diminish its negative impacts.

“We need to look into how boys are being socialized into men and the basic values that are being instilled in them. Social media is an unregulated space, where people can say things that are patently false and hateful. That becomes an agent of socialization and an important factor,” Cohan said.

Cohan also engages with strategies for the public to fight misogyny on a wider scale. A more active response to misogyny and increased support groups for women are both critical components of positive change.

“On an interactional level, we need to support people who identify sexism instead of vilifying them,” Cohan said. “On a structural level, we need to create groups that advocate for women in STEM and gaming because it’s in these all-male spaces where misogyny casually takes root.”

Gage Berger is a pre-major first-year at Seattle U who has noticed the discourse on social media revolving around controversial social media personalities or public figures. Berger says social media plays a prevalent role in spreading misogyny, particularly for adolescent men.

“If you don’t have a strong male figure or someone you look up to set a good example, especially for young boys, they’ll tend to look for a replacement somewhere. When there is nobody there to hold you accountable, it’s easy to do things that aren’t necessarily productive,” Berger said.

Berger argues that individuals should challenge themselves to develop and question their own image of masculinity as opposed to primarily looking online for guidance.

“It’s tough to not be influenced but you need to be able to know your values to determine what’s wrong and what’s right,” Berger said. “It can be tough when you don’t have a positive male figure”

Jack Brotherton is another Seattle U first-year film major who has noticed a growth in misogyny and other forms of prejudice on social media. While Brotherton acknowledges that social media plays a major role in spreading hateful rhetoric on a public scale, he asserts that it is possible for people to not be so easily influenced by what they see on social media.

“Social media is accessible and anyone can use it to take advantage of other people who aren’t very smart,” Brotherton said.

Contrary to Berger and Schroeder, Brotherton thinks it is possible for individuals, young men specifically, to view material on social media that may contradict their values and for those young men not to be directly influenced or detrimental impacted socially.

“I don’t take social media too seriously and that’s probably why I am not so easily influenced by it,” Brotherton said. “Maybe the problem is people are seeking guidance from the wrong outlets.”

A number of Seattle U faculty and students have acknowledged the need for discussions calling for a revaluation of where young men find outlets for self expression and personal influences. In the face of a shifting social media landscape, several voices in the university hope that the transmission of alt-right and misogynistic ideology online can be replaced by a positive and productive community.