Seattle U Instagram Post Initiates Frustration Around Access to Mental Health Services

“It was like a punch to the gut,” First-year Political Science major Jean Simpson recounted.

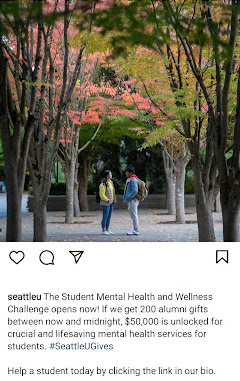

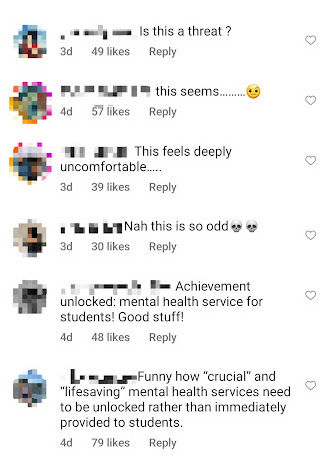

Seattle University shared an Instagram post that received significant backlash from the student body Friday, Feb. 24. The conversation around access to mental health services on campus bubbled over as students flooded the comment section. Nearly 100 responses outraged about the wording of the caption, as well as the methodology behind the fundraiser itself.

The post, which has since been deleted, was part of the university’s annual Seattle U Gives fundraising campaign to encourage donations to colleges, extracurriculars and programs. The post advertised the fundraiser for Seattle U’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), promising to unlock $50,000 for “crucial and lifesaving mental health services for students.”

Simpson was one of the first students to comment on and upload the post to her Instagram story. She had seen it shared among her friends, but had yet to see a public response to the post.

“The more I thought about it, the more I wondered what they were trying to achieve. I texted a few friends about it because I didn’t want to make a big fuss, but most of them were really shocked,” Simpson said “I couldn’t just let this sit, I needed people to notice and not skip over it.”

Simpson has been vocal on social media about mental health before, attracting attention from fellow students. She noted the frustration shared by many students.

“I got a ton of responses, maybe 20 people in my DMs asking me questions or agreeing or sharing their stories. It was kind of overwhelming because so many people were complaining to me because I was someone who understood. Most of the students here are just as disappointed and don’t know what to do about it,” Simpson said.

The Assistant Vice President of Alumni Engagement, Ellen Whitlock Baker, offered recognition of the for the poor wording while pointing out that the funding was not truly dependent on additional donations, but rather the 200 additional donations to unlock additional funding was a gamification tool to drive more funding.

“What we realized after the fact as people were responding was that the way that sounds with the words ‘mental health and wellness’ and ‘unlock money for critical mental health and wellness support’ does not read well, which we 100% realize, especially when taken out of context of all the other giving day posts.”

As the post circulated through students’ social media, it quickly morphed into a conversation about the bigger picture: some students at Seattle U argued they are disconnected from mental health services. Many commenters recounted their own experiences with the university. School stress, pressure from the pandemic and a lack of access to mental health resources culminated in this backlash after years of growing concerns.

Despite the outcry, Simpson is hopeful that Seattle U and CAPS may still be able to work with students to improve access to mental health services.

Despite the outcry, Simpson is hopeful that Seattle U and CAPS may still be able to work with students to improve access to mental health services.

“If they tried, they could make a comeback. I believe they could get us the support we need,” Simpson said.

Whitlock Baker noted that the mental health and wellness goals were sparked by conversations with Vice Provost Alvin Sturdivant, who notified the Seattle U Gives team that funding for mental health resources on campus was nearly depleted.

“We’ll have the final numbers soon, but we raised $53,120 for mental health and wellness. That’s almost two years worth of funding that they didn’t have,” Whitlock Baker said.

Given that the funding campaign has reached its goal of providing more resources to mental health facilities on campus, the school may have the opportunity to offer more robust support to students in the near future due to the combination of small donations and the large initial grant from an anonymous donor and Pat Kennedy & Melissa Ries.

However, others in the comments section of the post were far more critical of the school and less hopeful for future improvements. Remarks ranged from “this feels unnecessarily like a threat” to “vile behavior,” “unethical” and “disgusting and dystopian.”

The Seattle U Gives team responded to the criticism in the comments of the post before it was scrubbed from social media.

“To our Redhawk community—we appreciate your feedback and want to acknowledge that we hear you, and that the language used in this post should have been framed differently. Seattle U is committed to the mental health and wellness of our students as aligned with our mission to educate the whole person. Moving forward, our team will adjust and evolve our language and approach to Seattle U Gives in direct response to this feedback,” the comment read.

A similar update remains on their Seattle U Gives webpage, which does not have the same comments section system as Instagram.

One of the most liked comments on the post came from Alice Sampson, a first-year pre-business major. Sampson argued that a lack of seriousness toward mental health issues was demonstrated by the post.

“The post showed that the school doesn’t really care about students’ mental health. It was heartless,” Sampson said.

She alleges that her friends have tried to access help from CAPS and have received no additional support.

“It takes weeks or even over a month to hear anything back sometimes,” Sampson recounted.

Mien Nguyen Moc Le, a first-year psychology major, also shared concerns about the university’s academic departments’ treatment of mental health, and the availability of CAPS to struggling students.

“My classes drain every string of energy I have. I need a mental break every week, but then my absence will be penalized,” Nguyen said. “I reached out to CAPS, and they told me I would be better off looking elsewhere for help. I just stopped reaching out to them.”

These concerns are not new at Seattle U, as understaffing and overbooking appear to be growing trends for CAPS. However, the situation has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, when the university officially made the decision to host exclusively online services like telehealth and referrals. Simultaneously, college students have also reported increased rates of stress and mental health issues such as anxiety and depression.

Dominic Javar, a first year business marketing major, spoke about how the diminishing accessibility of mental health services coincides with an increasing necessity for them.

“It’s infuriating to see because so many students, especially post-COVID-19, have struggled to maintain a healthy relationship with their mental health, let alone balance that relationship with the weight of school,” Javar said.

Academic pressure plays a powerful role in the way students approach their mental health, especially in a university environment. The post also brought heightened attention to mental health in the final few weeks of winter quarter, where academic stresses are exacerbated by approaching finals. Javar also mentioned that he felt punished by the school and certain faculty members for prioritizing his mental health.

“The teeter-tottering effect seen in students falling in and out of mental stability whilst pursuing a college degree is degrading the value behind the university’s poor efforts to be there for their students,” Javar said.

In addition to the donation challenge being fulfilled, the university has publicly indicated a pivot toward providing more mental health resources to students. The university announced March 2 that it will raise tuition for the 2022-2023 academic school year by 3.75%.

The letter from President Eduardo Peñalver stated the increase in tuition was intended “to support a more comprehensive health and wellness program,” citing services such as 24/7 telehealth.

This news, combined with the Mental Health & Wellness Fund being the largest challenge of the Seattle U Gives campaign, illustrates the university’s effort to focus resources into mental health resources.

However, some students did not take the announcement as good news. Javar raised questions over the tuition increase and argued that sufficient telehealth services were already supposed to be offered through CAPS.

“I’m already struggling to pay for my tuition as is. This added expense only increases the amount of stress on my shoulders and innately makes me question if I’ll be able to afford attending this school in the long run. It’s scary when I’m the one having to pay for it all out of my own pocket,” Javar said.

Although the increased funding may lead to more accessible health services for students, the university faces a challenge in alleviating the concerns of students who have been disappointed with the university’s efforts so far.

“I’m disappointed in the school’s effort to make campus a place that I feel I am seen, mental struggles and all,” Javar said.

Despite student frustrations, students are looking for off-campus help, and are seeking each other for help when they are not sufficiently served by CAPS.

“Just because the school is not giving you the resources you need doesn’t mean you should stop looking for them,” Simpson concluded. “Keep looking for the help you deserve.”

Seattle U continues to confront the balance between responding to student concerns, acquiring sufficient revenue to provide resources and logistical pressures imposed by COVID-19. This year’s Seattle U Gives campaign inflamed conversation about mental health on campus.