Law School Conditional Scholarships: Merit-Based Reward or Predatory Admissions Process?

Madison Moreno, a second-year law student, went to an administrator, a steward of her education, to bring up issues surrounding her mental health and disability. Moreno was trying to get a course load reduction for her classes because of complications with her disability, and had fears of losing her conditional scholarship. Instead she was laughed out of the office.

With student debt in America at an all time high, and the average student loan debt for law students being over $160,000, losing conditional scholarships could mean taking on thousands of dollars more in loan debt, or even having to drop out

Conditional scholarships are awarded to students based on the merit of their applications, but they come with the condition of maintaining a certain minimum class ranking, with most having the requirement of staying in the top 50% of a students class.

In the 2020-2021 Academic year, 78% of students entering the law school as 1L students were given conditional scholarships. However, with 37% of students having at least half of their tuition covered, it is statistically impossible for them to all keep their scholarships.

With the increased complications of the COVID-19 pandemic, conditional scholarships were suspended for the 2019-2020 academic year due to the credit/no credit option.

Of the past five years—excluding last year—on average 33% of law students lose their conditional scholarships according to the Standard 509 reports, which details the amount of conditional scholarships given and taken away by the law school.

For student activists like Moreno, the system of awarding first-year students large scholarships just for many students just to have them taken away is inequitable, especially for those dealing with a disability.

“People have the attitude of, ‘if I help you do well, that could be you taking a spot in the top half that could have been mine,’” Moreno said. “When you tie how well you do to others having to do worse, it’s not a way to create an environment where people want to help each other and see others succeed.”

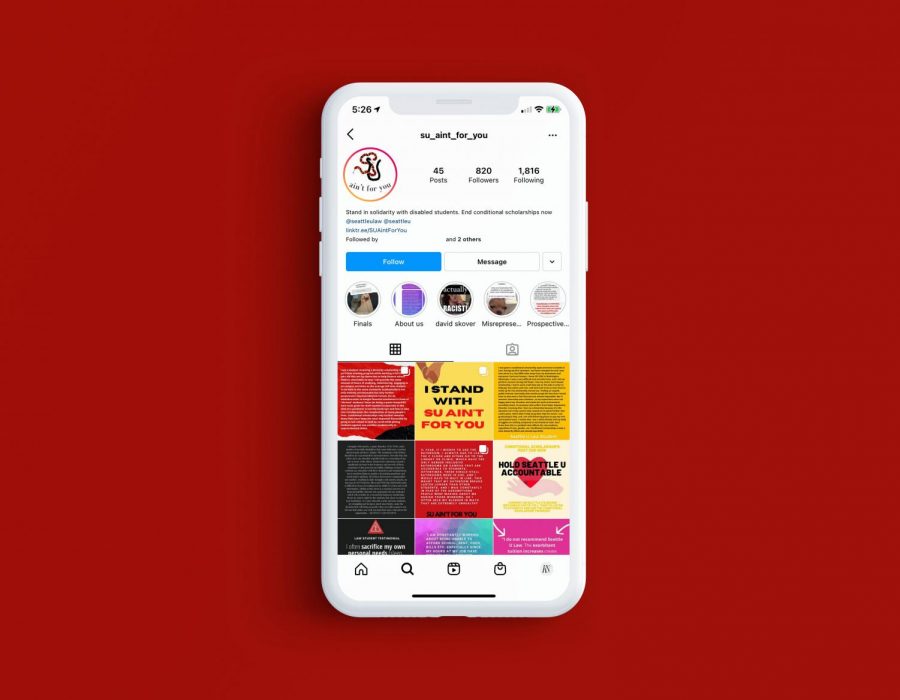

This group of student activists started the Instagram account @su_aint_for_you to raise awareness of the issues surrounding the conditional scholarship, especially for students with disabilities but also students of color, LGBT+ individuals and women. As a part of the campaign against the conditional scholarship, the students ran a survey via the account in which 145 student responses stated they were experiencing increased physical or mental health problems due to the conditional scholarship.

Cloie Chapman, a 2020 alumni of Seattle U’s law school has testified to the increased strain on student health caused by the fear of losing their scholarships.

“I was diagnosed with depression and anxiety in undergrad, but it got significantly worse in law school,” Chapman said. “Just the idea that I wouldn’t be able to finish the program because I couldn’t afford to continue without my scholarships without taking out thousands more in loans made my conditions so much worse.”

Student activist and second-year law student Liz McDonald argued that part of the reason @su_aint_for_you alleges the lack of support from Seattle U’s Law program is hard for students living with disabilities is the lack of support that the law school provides.

“For students with disabilities, trying our best without any accommodations feels like everything is against us,” McDonald said. “Even though we are doing nothing but trying to pay tuition and trying our best to become lawyers, we are getting pushed around and told we didn’t do good enough. It’s very disheartening.”

Due to the law school running autonomously from the undergraduate portion of the school, law students do not have access to the disabilities office. In place of an office, law students can only turn to one person, Associate Dean Kristian DiBiase, who started the position in January 2021.

Moreno argued that the lack of institutional support is causing students who need extra assistance in the classrooms due to their disabilities to slip through the cracks,putting them at increased risk of losing their scholarships, or even having to leave the law school.

“There is also another first year student this year that actually had to drop out because she was unable to get the proper support for her hearing impairment, because we don’t have that kind of support system in place to properly educate faculty and secure accommodations for these disabilities,” Moreno said.

There is an appeal process at the end of the year for students that lose their scholarships, however they must ‘demonstrate a catastrophic event.’ McDonald argued that this can be a retraumatizing or belittling process for students that faced situations out of their control or were experiencing hardships with their disabilities.

Additionally, required documentation of steps taken to address these issues need to exist, including therapy visits, which some might not be able to afford or have lost, adding increased barriers to keeping their scholarships.

While the law school administration was unavailable for an interview, Marketing and Communications Director David Sandler released a statement to The Spectator explaining their position on conditional scholarships and how they were addressing student concerns.

“Many law schools across the country award conditional scholarships,” Sandler said in an email statement. “The School of Law also acknowledges the burden placed on those students who do not meet the academic conditions to retain their at-entry scholarships. While the law school does not have the financial means to immediately eliminate all conditions on scholarships, we are committed to reviewing our scholarship policies and studying alternatives through race, equity and disability justice lenses.”

However, conditional scholarships do not exist at every university, with only 43% of law schools having a conditional scholarship program as of 2018. This number has been declining from 68% in 2012 ever since the ABA decision to require schools to disclose the number of students receiving and losing conditional scholarships in their Standard 509 report every year.

Other law schools in the Pacific Northwest have different scholarship systems. Lewis and Clark College and the University of Washington do not have conditional scholarships of any kind, and Gonzaga University has a conditional scholarship program based on a minimum Grade Point Average (GPA) requirement rather than on class rank.

Student activists including Chapman and Moreno, argue that the lack of conditional scholarships at law schools across the Pacific Northwest is evidence of other systems which can also work at Seattle U. They emphasized the importance of making sure that the money is allocated on the basis of need, in order to fulfil the university’s mission of social justice.

Chapman alleged a more insidious issue than just the Seattle U law program taking away scholarships, and asserted that conditional scholarships are a tool to lure in students to start law school, just to pull the rug out from under them a third of the way through the program.

“When you ask them about the condition, they reassure you that it is very easy to maintain, but they say that to every student that gets a conditional scholarship. The school knows that it’s statistically impossible for everyone to maintain their condition, but their only goal is to get you signed up so they can start taking your money,” Chapman said.

After pressure from student activists, Dean Annette Clark announced April 16 that all students who lost their scholarships this year would get 50% of the money back, stating that the university understood the unique struggles that students have had during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The plan is to fund the scholarship reinstatements by using surplus funds from this fiscal year, which are the product of reduced expenses as well as sacrifices undertaken by the faculty and staff, who did not receive budgeted compensation increases or any employer contributions to their retirement plans this year,” Clark said in the email.

Moreno said that giving back 50% of the scholarship this year is not enough, with the group of students remaining steadfast in their demands of a complete abolishment of the conditional scholarship. Moreover, Moreno takes issue with the messaging around faculty and staff, saying it feeds into the negatively competitive environment that the school has created in the law program.

“The faculty have been really supportive of ending the scholarship,” Moreno said. “With the cuts to pay raises and suspension of contribution to retirement accounts, those were already happening university wide, but the way that the Dean is trying to frame it is to pit students and faculty against each other. Allowing the administration to remain committed to their bottom line rather than to the campus community.”

For Seattle U Provost Shane Martin, who oversees the law school as well as the rest of the university, the school is listening to students and is beginning the process of figuring out how to change how conditional scholarships work at Seattle U.

“From what I understand students have put forward the complaint that the conditional scholarships are not in line with social justice, I wonder if their critique would extend to the entire grading system which ranks students…the scholarship is one piece of a larger system…of how law schools work,” Martin said. “I resonate with the idea that we would have a group that would look into this and make some recommendations.”

While the fight continues over the existence of these scholarships, Martin believes that a workable solution can be reached for the university, which is in a deep deficit, and for the student body that feels betrayed by conditional scholarships.

“We want all of our students to succeed including our law students, and while there is contention right now I believe that we have made a good faith effort to solve this issue,” Martin said.

Second-year law student Caitlin Hughes, said until the conditional scholarship was abolished, the students will continue their campaign of activism and education about this issue facing law school students with disabilities, and the campus community as a whole.

“We want conditional scholarships to be gone. All we are asking is for the acknowledgement that this system doesn’t work, it hasn’t worked for a while, and the university knows that. Just engage with us on this issue, let us know that we are being heard, because with the way we are being ignored it sure doesn’t feel like it,” Hughes said.

While student organizers continue to cry out for an end of the conditional scholarship, the issue remains unresolved.