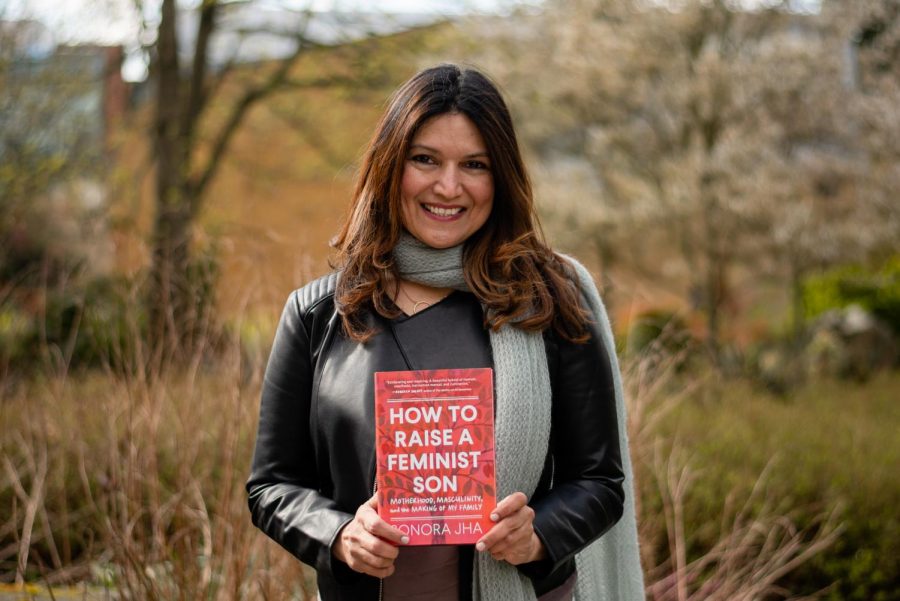

Sonora Jha Shares Insights on Raising a Feminist Son in New Book

Dr. Jha with her book: ‘How to Raise a Feminist Son.’

After dedicating herself to living a feminist life and instilling these values in her son, Seattle University Communications professor and Associate Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Dr. Sonora Jha, published her book, “How to Raise a Feminist Son.” Released April 6, Jha discussed the book in an interview with The Spectator.

KHM: What does feminism mean to you? When you think of feminism, what comes to mind?

SJ: As a young woman, it was more about resistance. Now, it is about living a full life in which everyone comes along––all intersections. It’s moved from being about myself as a woman, to it being about the culture and society we’re living in. Basically, [it is] about recognizing the full humanity of women, LGBTQ+ people and all the ripples across those identities.

KHM: Could you elaborate more on the importance of intersectional feminism?

SJ: I don’t see feminism without it being intersectional. I look forward to the day when we don’t have to say intersectional because it has become the only way to be a feminist. You cannot tease out racism or anti-racism from feminism.

If you want a full humanity for women, then what does that humanity look like? That humanity has to be given to everyone across gender, across physical ability, across sexual orientation––everything. If anyone is left behind, women are left behind. It becomes easy to make the argument that women and women identifying people do not deserve a full humanity.

My son is a man of color, I am a woman of color. If I am asking him to be a feminist, but he himself is disadvantaged as a man of color in the U.S., or he is advantaged in India, as belonging to a Brahmin family that I come from, a Brahmin caste, an upper caste family. Then, how can he be fighting for the liberation of women and the equal humanity of women if he is either underprivileged in one society or privileged in another society? Then that’s not about equity at all. So, that’s hypocritical of him, it’s hypocritical of me as a feminist.

KHM: Why was raising a feminist son a top priority for you?

SJ: I was raised in a very violent home, and I realized that that was gendered violence. I was afraid that my son would turn out to be like my father and brother. So first of all, it was a self-protective thing. I’m going to protect myself from my son, from this baby in my arms. In order to do that, I have to live a feminist life and I have to teach him to value the full humanity of women, starting with his mother. Then, it became a response to him because he was so tender-hearted. “Oh, this is how he wants to be, this is who he is, and if I don’t fight for his rights to be this way rather than him getting conscripted into toxic masculinity and being whatever our perception of men being strong. That’s not how he wants to be, so I need to fight for him to be the way he is. Feminism allows and encourages boys to be that way.

KHM: What can people who aren’t parents do?

SJ: Almost all of us have influence in the raising of boys or the changing of men, or the bringing along of men into a feminist life, into a feminist conversation.

If we’re talking about how to shape half of humanity into being just better and kind. It’s a thought book, and this kind of thought is for everyone. They can get involved in their schools, office culture and world culture. Everyone can say “how do I serve this cause of raising better men?”

KHM: You talk about how the work never really seems to be done. How do you avoid getting frustrated with that?

SJ: Oh my god, it is so frustrating. I talked about my son’s mansplaining, and he still does it. He can do it in an instant, like Facebook messenger, he can mansplain to me, and then he can do it in person. I do get frustrated with my son and with society. Thinking about “what the heck, when will change happen?”

There’s a feminist movie star in India, Shabana Azmi. Someone told her that, “change may not happen in your lifetime, and if you accept that fact and still work for change, you have to work for change despite knowing that you may not get to see the benefits of that change in your lifetime, but it’ll have a ripple effect.” That kind of puts the lid on frustration. Then you say, “alright I accept that, and I will continue to do this work because it may not happen in my lifetime.”

If I’m not around and my son ends up being a really good father or grandfather to his kids or grandchildren, and works toward a better feminist world, or is just a great colleague to the women and LGBTQ+ folks at work, that is great. I may not see it, I may not be there to enjoy it, but to know that it could be beyond me and my lifetime helps me focus and not feel frustrated.