“Somewhat Informed: Zodrow’s Performing Arts Column; Can Theater Handle a Transition to Online? Sort of.”

Broadway.com streamed a live production of the 2013 comedy “Buyer and Cellar” on April 11. The Jonathan Tolins play has been lauded by many theater fans and critics as proof that theater can thrive online. The play itself is a delight, though it may not prove to be the good omen that those behind the curtain are praying for.

“Buyer and Cellar” is a one-man show about Alex More, an increasingly desperate actor in Los Angeles who finds himself fired from his job as a Disneyland cast member. His boyfriend Barry is a Hollywood business type, but More himself does not have many jobs coming down the line, even if he studied drama at Northwestern.

A previous work associate (and occasional makeout buddy) from Disney reaches out to offer him a job. It’s strange, a rich old woman wants someone to act as the sole staff member in her basement, which she has furnished to look like a mall. Needing the cash, Alex begrudgingly accepts and starts his job, sitting in the basement of a grand mansion, waiting for the mall’s sole customer to arrive.

After several days, the woman who presents herself as the owner of the estate and Alex’s employer is none other than Barbra Streisand. He’s not a superfan, but Alex is nonetheless stunned that he is in such a strange arrangement with the theatrical icon.

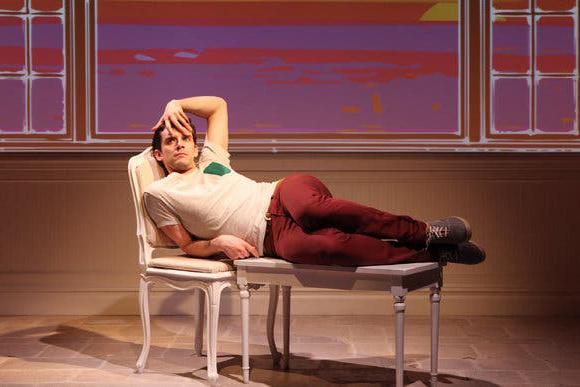

Hilarity ensues from this point onward. The real thing that brings the show together is Michael Urie’s performance. He plays five distinct characters and lends them all a unique feel. One-man shows can often fall victim to the sense that a single actor is talking to themselves for two hours. This is not the case in Broadway.com’s production. Urie shows his talent for comedy and character composition and proves that the role, which he originated in 2013, is perfectly suited for him. Tolins’ script isn’t particularly profound, and doesn’t have much of a message, but triumphs due to the sheer joy it creates.

The real brilliance of the play is not its thesis (if it even has one), but rather its exploration of the LGBTQ+ community’s relationship with Barbra. Time Out magazine’s David Fox describes the connection between gay men and the musical diva as “cosmic.” This is likely due not only to her talent as a performer, but also her early support of LGBTQ+ rights.

In a letter to Billboard celebrating Pride Month in 2017, Streisand described her connection to the gay community: “The first time I ever sang for a paying audience was at a gay club, The Lion, in Greenwich Village. I was 18-years-old and had never been in a nightclub before.”

Since then, despite vehement public prejudice toward the LGBTQ+ community, she’s been a strong advocate, from the AIDS epidemic under the Reagan administration to marriage equality under Obama. “The gay community supported me from the start, and I will always be grateful,” Streisand said.

However serious Streisand’s efforts to support the queer community have been, the play itself revels in the kind of witty-fun that one could expect to find in any of Barbra’s most whimsical performances. Urie’s impression is silly without seeming reductive, though the end of the show does cast the star in a surprisingly negative light. The decision is quite comedic, however, and serves as a satisfying end to the narrative.

Directed by Nic Cory and Paul Wontorek, the online show was sparse and utilized two cameras and a few lights set up in Urie’s apartment. Tolins introduced the production, and Urie managed to execute a skilled and magnetic performance to two live-stream quality cameras in his living room.

Vulture’s Helen Shaw labels “Buyer and Cellar” as a “proof-of-concept for streaming theater.” The New Yorker raves that it will “make you want to watch theatre online.” These are both partially true. I missed the undeniable energy and presence of live theater, but will also admit to enjoying watching a play in sweatpants while in bed. The worry of the performance losing its ‘theaterness’ by being filmed was mostly abated by the extremely sparse editing and the fact that it was broadcast live. The lack of sheen (Urie was being recorded by the airpods he was wearing throughout the performance) lended a feeling of connection with the performer that makes drama so special.

However, there are some significant caveats to the notion that “Buyer and Cellar” will lead to a boom of online theater productions in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis. For one thing, there aren’t a lot of one-person shows. The brilliance of Broadway.com’s production was the ability of everyone involved to social distance, stay at home or both. Don’t expect to see a livecast of actors standing six feet from each other performing “West Side Story” in Stephen Sondheim’s living room.

There is also the issue of the technical bugginess of the livestream format. For all the charm of the Broadway.com production, it did suffer from moderately-frequent audio hiccups and a few dips in video quality. The producers likely found themselves in a Catch-22 between live streaming—which makes online theater feel more like theater—and video, which compromises the integrity of the live experience while preserving the technical quality of the broadcast. They made the right choice, but it wasn’t without drawbacks.

Overall, “Buyer and Cellar” was a light in the darkness for many theater fans. For those who had never seen the show, it was a privilege to get acquainted with such a delightful play and the talent of Micheal Urie. However, the viability of online theater still remains to be seen.