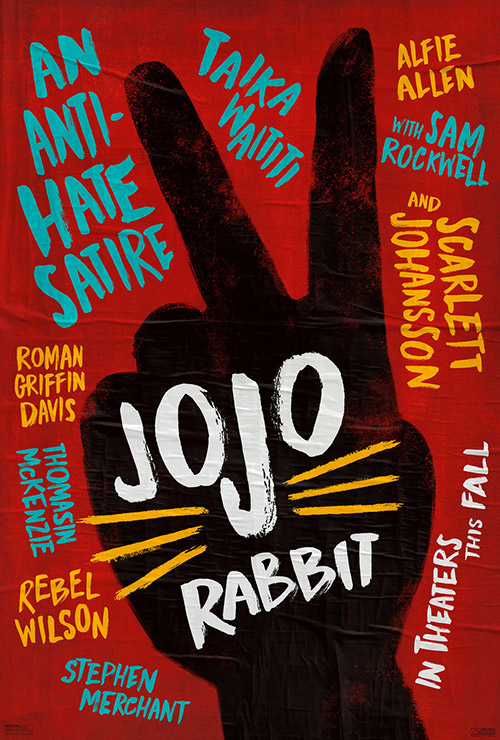

“JoJo Rabbit”—Taika Waititi’s Most Confusing Masterpiece Yet

In an amusing yet unsettling tale set during late-stage Nazi Germany, “Jojo Rabbit” is film director Taika Waititi’s newest movie. Having premiered at the 44th Toronto International Film Festival, the film was released on Oct. 18 in the United States. As the opening credits roll, archival footage of Nazi rallies plays, accompanied by a German version of The Beatles’ “I Want To Hold Your Hand.” From this first scene, the film has a dissonant tone. Sitting in the crowded theater, I felt an uncomfortable urge to tap my toe to the joyous music before being dragged back down to reality by the sight of hordes applauding fascism.

“Jojo Rabbit” tells the story of a 10-year-old German boy named Johannes “Jojo” Betzler— English actor Roman Griffin Davis’ debut role. Jojo is unpopular, immature, and blindly, fanatically fascist. He lives with his progressive mother Rosie (Scarlett Johansson) and has an imaginary best friend: Adolf Hitler.

The film begins with Jojo preparing for his first day as a member of Hitler Youth at the regime’s training camps. With his confidence bolstered by his imaginary version of Hitler (played by the Waititi himself) Jojo runs off to training, “heiling” exuberantly as he goes. The training camp is a delightful and confusing replica of camps seen in films such as “Wet Hot American Summer” and “Moonrise Kingdom.” It’s got hijinx, comical injuries and a jubilant bookburning.

Jojo, however, isn’t at Hitler Youth for long and ends up as an errand boy for the local Nazis. With his new role in the German war machine, Jojo finds himself with a lot of spare time on his hands. While home alone one day, Jojo discovers that his mother has done the unthinkable: hid a Jewish girl in their home.

Jojo’s mother is protecting Elsa, a 17-year-old girl who’s hidden in the walls of the Betzler’s house. Her introductory scene replicates monster introductions from horror films— and in Jojo’s mind, Elsa is about as monstrous as monsters come. Jojo sees everything through a black and white lens. Hitler is the ultimate hero, and Hitler’s enemies are Jojo’s enemies. Fascism is the ultimate ideology and Jojo is the best little fascist imaginable.

Yet as the film progresses, Jojo’s blind devotion melts away into uncertainty. The satirical Nazi movie has been done before, but there’s something different about “Jojo Rabbit.” Centered around children, this film has a disturbing tone to it. Watching children excitedly “heil,” burn books and prepare for death in battle leaves one feeling sick.

The images of children growing up accustomed to fascism are unfortunately relevant to the present. Perhaps what is most disturbing about the film is that certain elements of it don’t seem like they took place 74 years ago. Aside from the period costumes, “Jojo Rabbit” is a modern story. The imagery of blind devotion to an authoritarian government strikes a relevant chord.

“Jojo Rabbit” isn’t just supposed to be a retelling of an old story. There is a contemporary echo disguised as a historical story. It’s not surprising that “Jojo Rabbit” is full of originality. Waititi is known for changing things up. His most popular films “Thor: Ragnarok” and “Hunt for the Wilderpeople” are both familiar in nature, one being a superhero movie and the other a dark comedy, yet wildly imaginative.

Waititi’s inventive side strikes again in “Jojo Rabbit.” The film is weird, heartwarming, hysterical and heartbreaking. In a movie that could have been tonedeaf (a comedy with a Nazi protagonist who’s imaginary best friend is Hitler), Waititi manages to create something beautiful and resonant with his own Jewish identity. Perhaps what makes the film so beautiful is how Waititi flips protagonist Jojo’s narrative on its head. When the audience is introduced to Elsa, they are seeing her through Jojo’s Nazi-addled eyes. She’s the monster.

By the end of the film, however, she’s the heart of the story. She’s the character who shifts the narrative through the changes she brings to Jojo’s worldview. Elsa’s character is familiar in that she represents the hidden-Jew trope, but she serves a different role than its usual tragedy. She’s the real hero of the movie. Elsa teaches Jojo to lose his biases, and she represents human capability to improve.

I’ve never seen a film like “Jojo Rabbit” before, and I don’t think that any film like it exists. Viewers are bound to leave “Jojo Rabbit” feeling similar to the film’s protagonist: full of questions and broken expectations.

The editor may be reached at [email protected]

![Jordan Ward [REVIEW]](https://seattlespectator.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ward_1-600x400.jpg)

![COWBOY CARTER [REVIEW]](https://seattlespectator.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Screenshot-2024-04-10-at-7.37.52 PM-600x349.png)

Barbara Reeves

Nov 14, 2019 at 9:37 pm

Enjoyed reading your story. This movie reminds me of a book I have read. “All the The You Can Not See”.

See you soon.