At Seattle University, maternity leave is a topic buried in the calculated wording of an 80-page Human Resources Policy Manual. Some people–staff members, faculty and students–don’t know how the fine text applies to them, let alone what they need to do if they wish to adopt or have a child.

Mallory Torgerson-Preuitt, an advising services coordinator, is surrounded by this issue, both at work and at home. She has heard similar stories of confusion and frustration from countless women around her. These discussions sparked her interest, and inspired her to look deeper into the policy for her capstone course in her Masters in Public Administration degree. What she found, she said, was shocking.

Parents she spoke with complained that the policy created uncertainty about their salary and having enough time to take care of their newborn child.

“I could hear the same major issues come up over and over again, and I wanted to look into what the policy was, why the policy worked the way it did, and how the policy impacted people at the university,” Torgerson-Preuitt said.

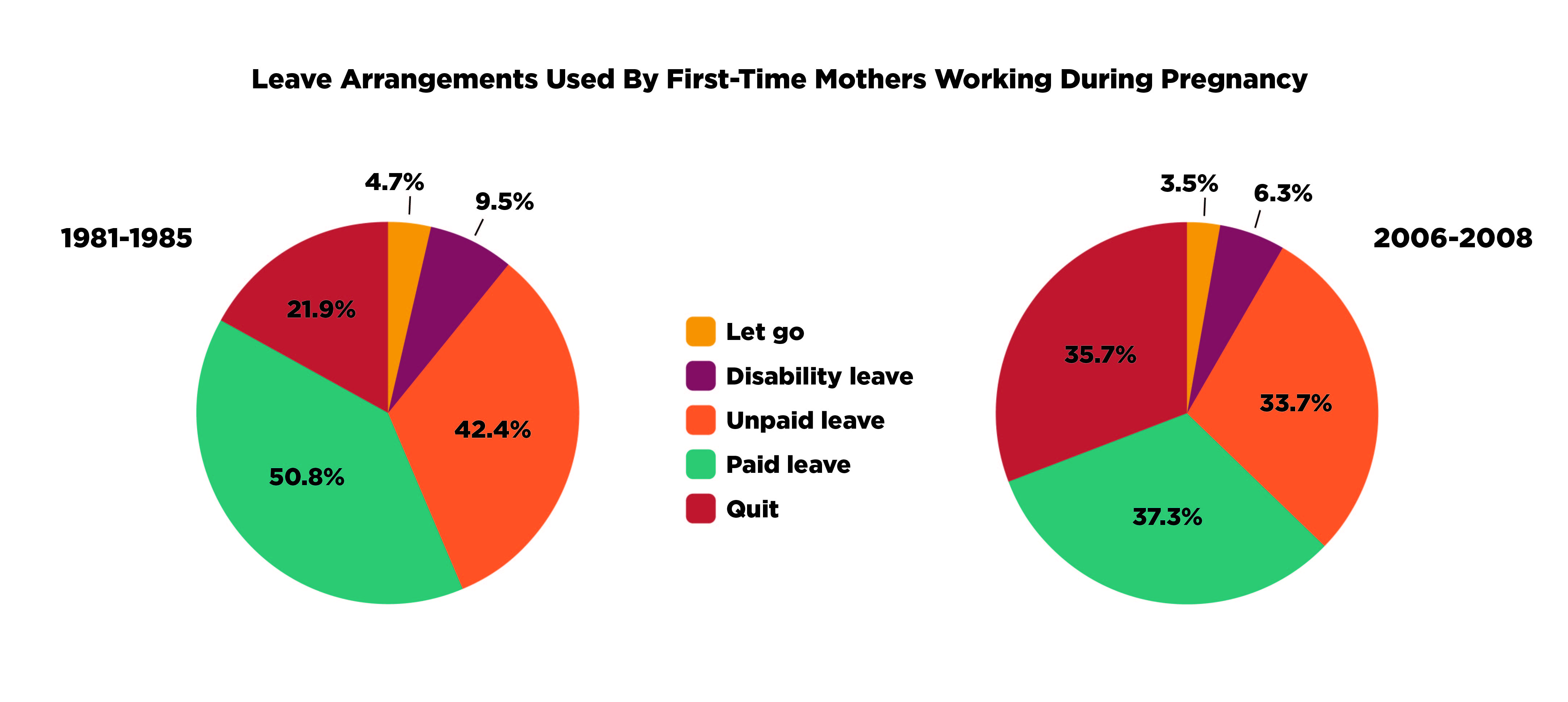

Seattle University does not offer paid maternity leave, something not unusual in the United States. The U.S. Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), is a federal policy that creates an opportunity for eligible faculty and staff to take unpaid leave for pregnancy, childbirth, and placement for adoption and foster care. This policy states that staff that the university has employed for at least a year and who have worked at least 1,250 hours during that time are “generally entitled” up to 12 workweeks of unpaid leave.

If the staff member wants to be paid during that time, they can use their accrued sick leave and vacation time for partial pay. Two partners who are employed by the university may be limited to splitting the 12 workweeks of leave under certain circumstances

If a staff member is eligible for FMLA, they have the option to use their accrued vacation time and sick leave for partial pay. When they return, they may not have any vacation time or sick leave remaining if they decided to use it over the course of their leave.

“When you’re planning on taking a time away where you’re not going to be paid your full salary or you might not be paid at all for certain parts of your leave, that can be really stressful and really damaging to a family with a new child,” Torgerson- Preuitt said.

Torgerson-Preuitt’s passion on the subject led to her husband, Montgomery Preuitt, an Interdisciplinary Liberal Studies major, to do some research of his own. In one of his classes, Preuitt did a group project on the policy, studying the stigma of the pregnant body. Like his wife, Preuitt was shocked as he looked deeper into the policy.

“I think that’s the big shock- that you would expect a school like Seattle U to have some form of paid [maternity] leave, but to have no paid [maternity] leave is kind of surprising to most people,” Preuitt said.

Preuitt explained that his issue with the policy was primarily that it was inconsistent with the university’s mission. He doesn’t believe that the policy accurately reflects the mission at its core.

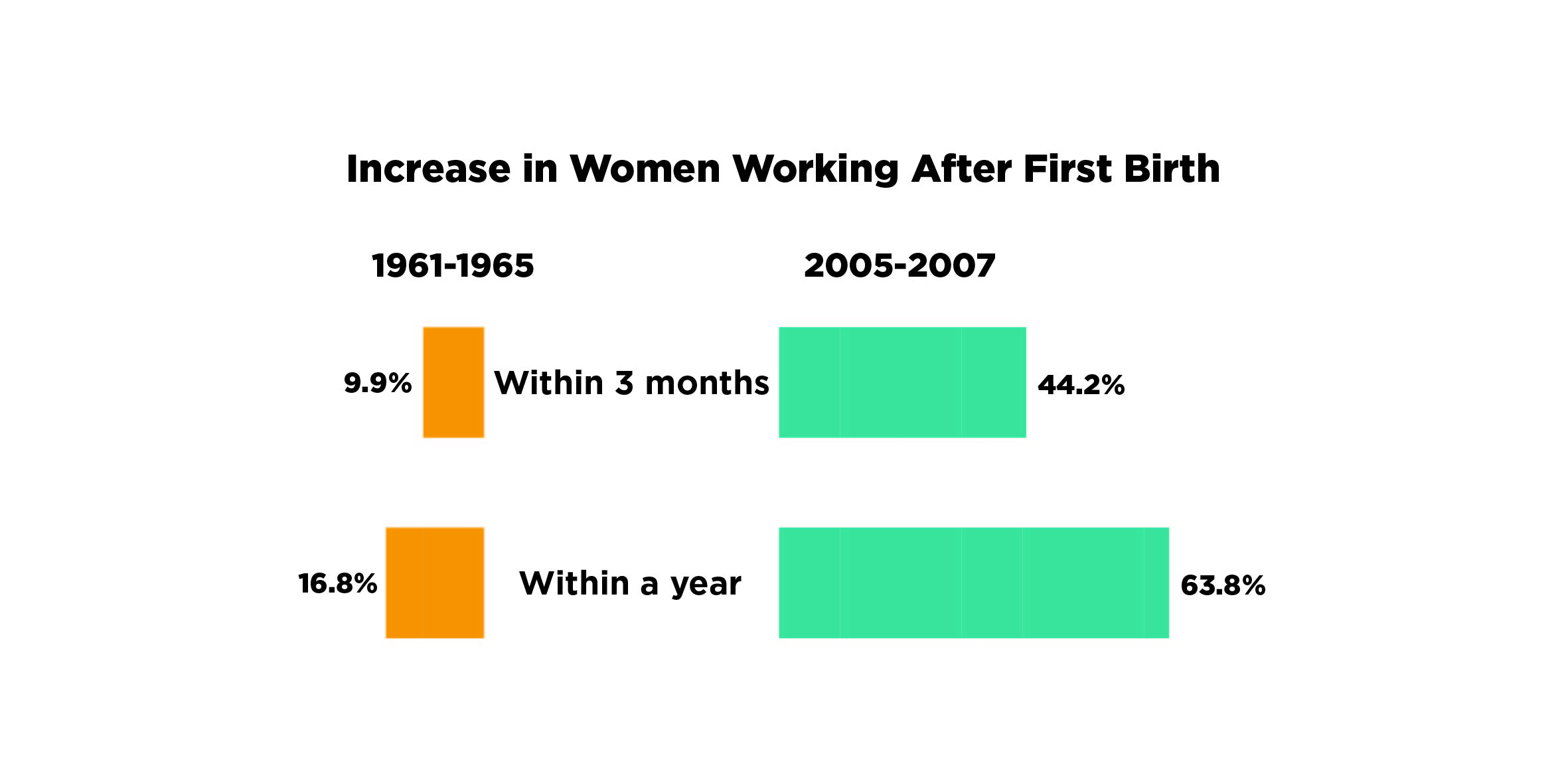

Although unpaid maternity leave is common in the United States (where only 12 percent of U.S. private sector workers have access to paid family leave through their employer, according to the United States Department of Labor), it is becoming increasingly in demand that institutions offer their employees paid maternity leave.

The city of San Francisco just passed legislation that mandates up to six paid weeks for maternity leave for workers, and Microsoft, a Seattle company, has one of the best maternity leave policies in the country.

Dr. Claire LeBeau, an assistant professor of psychology at Seattle University, focused her dissertation on the experience of first time mothers and is now researching parent couples on the transition to parenthood.

LeBeau offered insight into how huge of a change parenthood is to a mother’s body and life, and that getting used to that shift takes time for both parents.

“For a lot of folks, especially first time parents, it’s a huge adjustment and it takes a lot of effort to figure out divisions of labor, who gets up in the middle of the night, how do you cope with sleep deprivation, as well as sort of the recovery after birth,” LeBeau said.

She explained that putting a baby in childcare too early often increases their risk for sickness and infection, and that a chunk of time is needed in the early stages of the infant’s life to bond to their parents.

“When you’re planning on taking a time away where you’re not going to be paid your full salary or you might not be paid at all for certain parts of your leave, that can be really stressful and really damaging to a family with a new child.” – Torgerson-Preuitt

Some mothers who have been through the process of maternity leave at Seattle University feel as though the policy doesn’t offer as much of an opportunity for the smooth transition that Dr. LeBeau described.

Rachel Doll O’Mahoney, a Campus Minister, has gone through the process of maternity leave with two of her children at Seattle U.

She stated that while she knows Seattle U is not exceptionally bad with the policy, she expected more from an institution with such a deeply ingrained social justice attitude as well as a connection to the Catholic Church—which has historically stressed the importance of family.

“The standard in our country for maternity leave is a bad standard and Seattle U, I don’t think, is reflecting its Catholic identity in just following the status quo of the Family Medical Leave Act,” Doll O’Mahoney said.

Her critiques of the policy include that she found the information in the Policy Manual difficult to decode and recommends a step-by-step checklist that allows staff members to be organized and thorough while learning about the policy. Doll O’Mahoney also said that, as an institution, Seattle U is not making any movement to make a stand as being supportive of family life with the policy.

“It’s been hard—I certainly don’t regret having children, nor do I regret working at Seattle U, but those things happening simultaneously in the two times I did it was complicated, and stressful, and financially very tenuous for us,” Doll O’Mahoney said.

Along with critiques on the existing policy, there are also constructive ideas that could improve the policy and eliminate or lessen the stress of the expectant parent.

“I think that if staff and faculty would be given the three months paid without bankrupting personal leave—especially sick leave—upon returning, I think that would be a really great scenario,” Torgerson-Preuitt said.

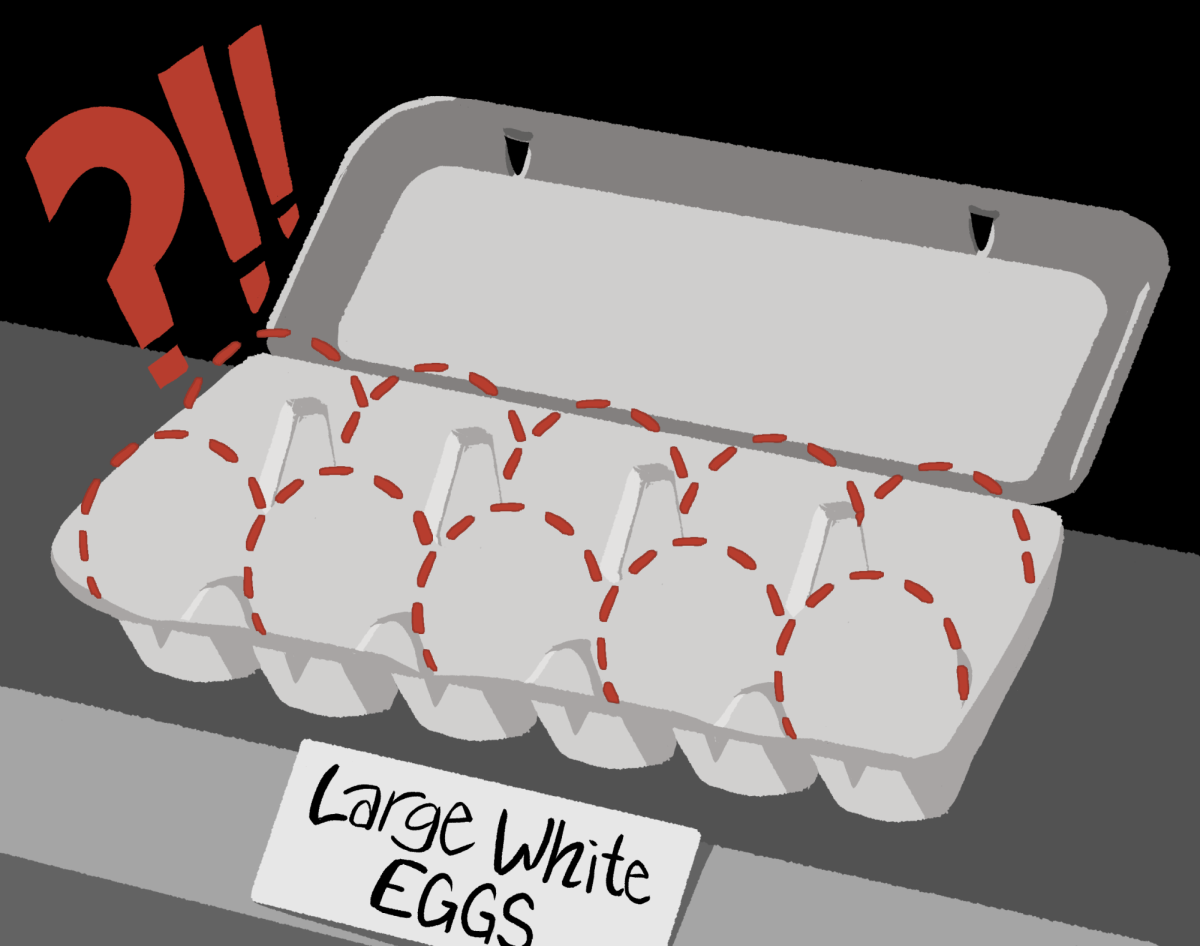

For many, the bankrupting of personal leave is an especially shocking aspect of the policy. Some parents are afraid that, without this sick leave or vacation time built up, they won’t have the flexibility to deal with an unexpected problem, like if their child becomes sick.

“In terms of maternity and paternity leave, those early moments are really important, so whether it’s affording time or pay, or offering really good childcare options for helping families grow in those early moments is really vital,” LeBeau said.

As policies begin to shift across the United States with a new administration in the White House, it is hopeful that the Seattle University campus can remain open and flexible about our own policies to better the experience of everybody involved at this institution.

When the Spectator reached out, Human Resources was unable to comment.

Tess can be reached at

towen@su-spectator.com

Tonja Brown

Jan 12, 2017 at 9:41 pm

Great article Tess! If you are looking for more experiences from SU parents, I would be happy to speak with you.

Rebecca Severson

Jan 13, 2017 at 2:54 pm

Agreed, I would be happy to share my experience / engage in this important discussion!