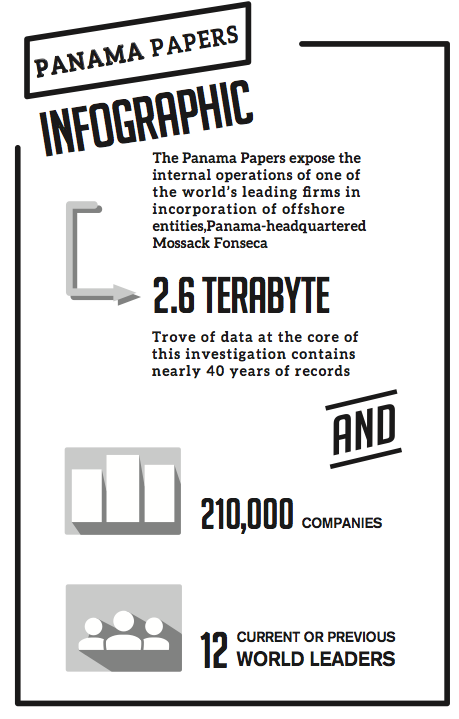

What do the Prime Minister of Iceland, a French Bank, and David Cameron’s father all have in common? Their names were among the hundreds included in the 2.6 trillion bytes of information in the Panama Papers, the largest financial information leak to date on offshore banking.

On Sunday April 3, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) went worldwide with information that an anonymous voice provided to them. The data leak included 11.5 million files from the Panamanian Law Firm Mossack Fonseca. Over 130 public figures as well as 14,086 companies had worked with the Panamanian firm to create shell accounts—or hidden bank accounts that take advantage of looser tax and incorporation laws—in Panama and countries all over the world. As a result, the money has not only been hidden from the public, but in many cases also avoided domestic taxation.

The response has been varied. In Iceland citizens took to the streets, calling first for the resignation of prime minister Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson and then for reforms within the government itself. Two days after the papers leaked, Gunnlaugsson stepped down, and will be replaced by Iceland’s Agricultural and Fisheries Minister Sigurdur Ingi Johannsson. Société Générale appeared in court in Paris on Monday for questioning on its facilitation of hiding money with Mossack Fonseca. The government investigation is looking into the legality as well as effects of the multinational banking firm’s actions. In Britain, the media launched a full scale investigation of Ian Cameron and the relation of his offshore accounts to his son. Using the money in a unit trust fund—a pooling of investments in stocks to mitigate risk—he argued that all profits were taxed and that his son currently has no involvement in the accounts. However the coverage has sparked a negative response from the British public, resulting in protests outside the Prime Minister’s home.

What stands out from these papers is the diversity in actors, usage and effects of these accounts. The ICIJ exposed what they called a shadow network, one that they believe is responsible for the massive immoral uses of money in the world. While few argue against the harmful effects some of these accounts have had, some claim we must be more exact in our critique.

“It is not necessarily the case that anyone who has created a shell corporation and is harboring their money in a shell corporation in a place like Panama or the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands [are] necessarily bad guys,” said senior finance lecturer David Carrithers. “That being said, a lot of them are and there’s the problem.”

For Carrithers, the problem is not with the system, but who uses—or misuses—it. He explained that since these financial systems were set up as amoral, and they have been manipulated by those with power.

“It’s not the amount of money, but who’s doing what,” said professor of finance Vinay Datar.

Pointing out that the types of financial systems being used by those in the leaked documents have been around for over a decade, he emphasized that the institutions themselves are completely legal. Moreover, Datar explained that many of the companies involved were investing in Panama, and that keeping their money in those banks made economic sense.

Adding to the concern, Carrithers worries that the immediate effects could hurt the Panamanian economy and the Panamanian people.

“[For] Panama, a large part of its economy is in its banking industry, and if the knee-jerk reaction is ‘We’ve got to eliminate this’ you’re talking about impoverishing an economy. That’s not a good thing for anybody,” said Carrithers.

A combined effort of journalists from over 80 countries, the ICIJ states that their goal is to expose a system that enables crime and corruption. Professor of communication Gary Atkins sees this organization’s role in the leak as reflecting the need for investigative journalism in a globalizing world, as well as how it

is evolving.

“Often government is not doing what you think it should be doing because they’re simply understaffed,” said Atkins. “In a way investigative journalism is like guerrilla warfare, you can only pick off certain things. What do we know? And what do we not know?”

The data from the Panama Papers is still being looked through by the 100 organizations that have partnered with the ICIJ on this investigation. Atkins believes that though the leak is now public, there is still much work to be done. As more names come to light, and moves are made to hide the truth, he asserts that the role of investigative journalists is as important as ever.

Jason may be reached at [email protected]