An essential part of Seattle University’s mission as a Jesuit Liberal Arts institution involves educating students in a holistic manner and providing them with a strong base in a wide variety of subjects and skills, along with a targeted focus on their major. The school seeks to accomplish this mission through two different pathways, those being the Honors program and the University Core, or UCOR for short.

While the two are quite different in a variety of ways, they both strive to accomplish similar goals and to prepare students for post-college life with a diverse set of skills and knowledge. Each program is designed with a great deal of intentionality, and the different approaches offer various benefits that appeal to different groups of students. In striving to achieve their purpose, the programs must navigate their own challenges and shortcomings, with faculty working hard to adapt the courses to provide students the best experience possible.

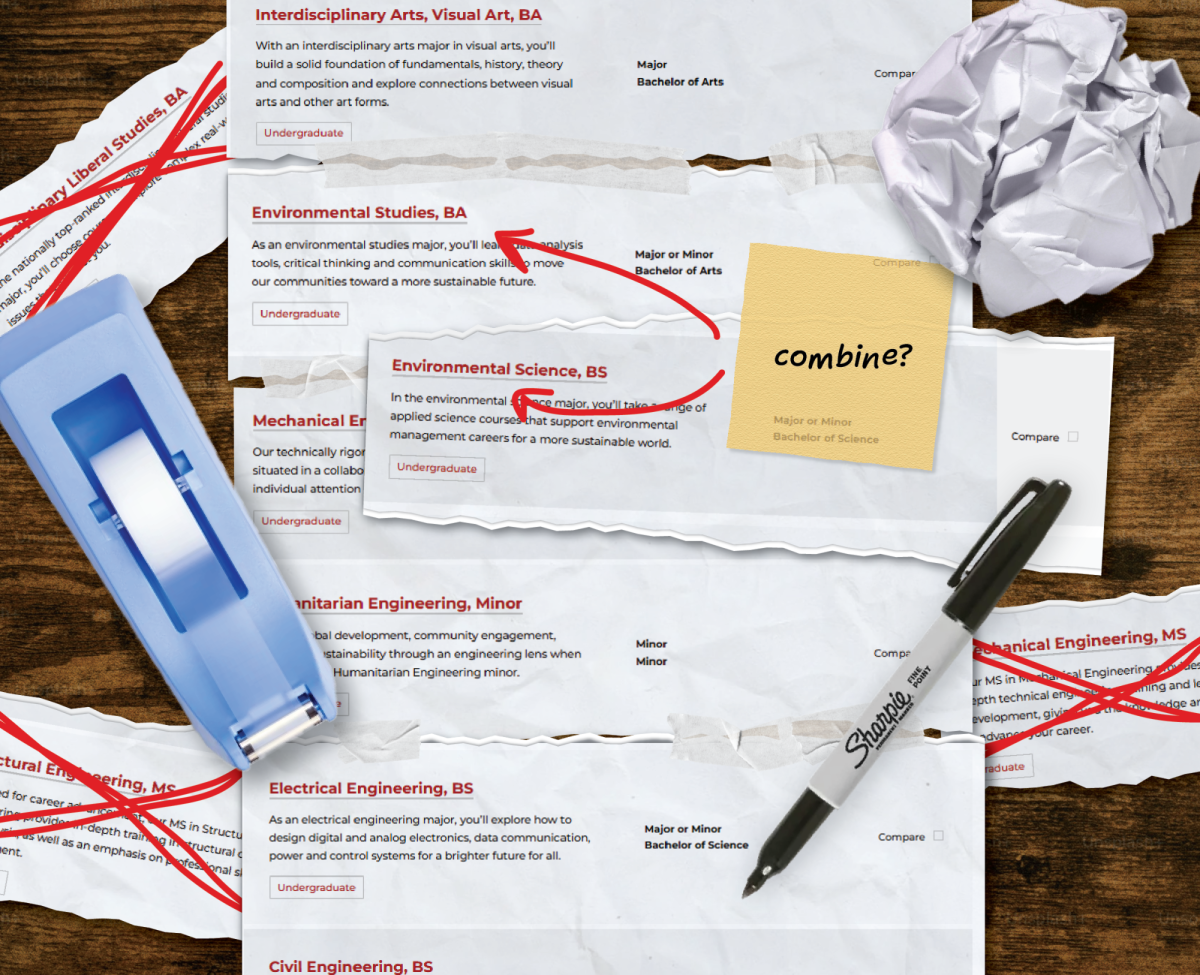

UCOR is the prescribed pathway for most Seattle U students. Approximately 90% of students go through the program to complete their core requirements. Students take 12 courses throughout their time at the school, with varied and specific options available for each course. They cover writing, math, natural and social sciences, philosophy and more.

Courses are designed to be specific deep dives into a certain topic, straying from a distribution model that has become a norm at many other universities, where students take an intro-level course to an entire discipline, barely scratching the surface. UCOR gets students to engage with one very specific subject, often a passion of the professor who is teaching it, in a much more nuanced and pointed way. In the process, UCOR courses attempt to integrate Jesuit values of social justice and community action.

Lydia Cooper, director of the UCOR program and professor of English, emphasized how important the specific nature of UCOR classes is to the program.

“You’re not necessarily learning that kind of basic intro to the entire field, but it’s a deep dive that hopefully is something that’s way more interesting and engaging and gives you an appetite to learn more if you want to,” Cooper said. “If we want to build lifelong learners, people who are curious, open to the world, then we shouldn’t bore them to death and force them like automatons through the exact same set of courses. That seems counterintuitive, so the ability to choose is really important.”

Cooper’s response touches on another hallmark of the program, which is the ability to choose one’s courses. Students are encouraged to fulfill their requirements by selecting whichever courses they feel are most interesting and applicable to their interests.

As far as teaching UCOR classes goes, professors report that the classes often allow them to be immersed with the student body and the subject matter in a way that regular, lecture-based major classes often do not.

Professor of Philosophy Eric Severson teaches UCOR classes and works on designing the future of the program. In an email to The Spectator, he explained some of the benefits of the UCOR program.

“The Core, however, uniquely combines students who come to philosophy from every discipline at the academy. When learning is collaborative and inclusive, students teach one another — and me! — about the way philosophy entangles with their discipline, their culture, their history, their work, and their passion for justice,” Severson wrote.

Students report varied experiences with UCOR. Many enjoy the program, like Diego Borromeo, a third-year international studies major.

“I’ve had good experiences with my UCORs. Specifically, Philosophy of The Human Person. I really enjoyed that class, and the teacher was really good,” Borromeo shared.

Borromeo also pointed out a few frustrations with the program, especially with the way course selection and scheduling work.

“My only frustrations would be if there was a specific UCOR course that I wanted to take, and my registration time was later, then it would be full pretty immediately,” Borromeo shared.

UCOR faculty also acknowledged many of the logistical difficulties that such a program faces. Cooper explained that the process of signing up for classes can be difficult.

“It’s not very visible for students and it creates challenges for students in building schedules really easily in my Seattle U,” Cooper said.

Additionally, the way that course enrollment works makes the issue even more difficult to address, as the school only offers as many courses as there are students to take them, meaning students with late registration times have a very limited selection of courses.

While UCOR faculty can’t directly change the way course sign-ups work, they are working in other ways to help the program evolve. UCOR is currently being redesigned for the 2026-2027 school year to include new courses at the start and end of the program that involve more direct engagement with its values.

“[The new UCOR] is not wildly different from what we’re doing, but it’s much more focused on that learning and action… I’m really excited about the new core because I think it’s just a more honed, clear story about what we mean as Seattle University,” Cooper shared.

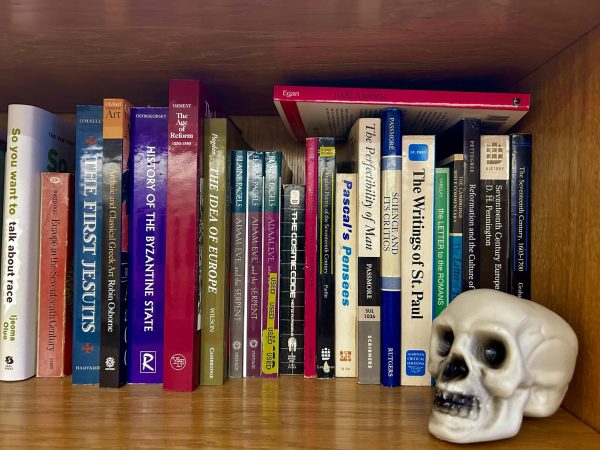

The Honors Program is the alternative way for students to fulfill their course requirements. The program uses a cohort model, seminar-based classes, prescribed curriculum and increased rigor to give opted-in students a way to engage with a set of core curriculum that is more specifically focused on philosophy, literature and history.

It takes the form of three tracks, which students apply to at the same time as their general admission applications. One track is called Intellectual Traditions (IT), and it extensively focuses on the three core subjects (literature, philosophy and history) and their evolution and representations in different time periods. The next is Society, Policy and Citizenship (SPC), which is similar to Intellectual Traditions in the first year but has a greater emphasis on the social sciences in the second. Finally, there is Innovations, a track designed to allow students with rigorous schedules and credit requirements to still participate in honors. It focuses on much of the subject matter through a STEM-adjacent lens.

Each SPC and IT Honors student is placed in three classes each quarter with the same cohort of classmates, with class sizes often smaller than 20 people. These students stay together throughout their first two years, taking each Honors class together. Innovations students take two Honors classes instead of three and complete Honors classwork into their junior year.

While Innovations may seem like the black sheep of the program, its addition in 2016 allowed a much greater diversity of academic majors to access the program and all of its perks.

Vinod Acharya is a professor of philosophy and assistant director of the Innovations track.

“We’re grateful that we’re still able to do this because these majors didn’t even get to be part of the Honors program in the past,” Acharya said.

The Honors program offers a variety of ancillary benefits, including significant one-on-one attention from an advisor, priority class registration, a $1,800 yearly scholarship and various community building events, with formals, gatherings and plenary events each quarter.

Marc McLeod, professor of history and assistant director of the IT track, emphasized the unique amount of support that Honors students have access to.

“Most administrative positions do not have the same degree of one-on-one advising that [administrators] do, because that’s a hallmark of the program,” McLeod said. “One [benefit] is the degree to which our curriculum is interdisciplinary but also integrated… there is an effort to develop effective communicators, both in writing as well as in speech and verbally.”

Owen Daryani, a third-year history and political science major and a graduate of the SPC track, shared his satisfaction with his Honors experience.

“I had a great time doing Honors, and it’s very fulfilling. I became a better writer and reader for sure. I built a lot of connections to the professors, which is probably the most valuable thing I got out of it,” Daryani said.

However, some students struggle with the intense workload. Borromeo was initially an Honors student but dropped out of the program due to the workload and found much more success in UCOR. Even in the first quarter of Honors, reading loads can consistently be up to 50 pages per class each night, along with greater length requirements and quality standards for assignments.

In addition to monitoring and changing the curriculum to fit schoolwide standards and the program values as part of the “Reimagine and Revise Our Curriculum” initiative, Honors faculty are working with students and with the curriculum to make sure that it still serves generations of students that are academically impacted by the effects of the pandemic, virtual learning, and social-media-influenced attention spans.

“It doesn’t mean that we scale back our expectations, but we also have to make sure that we are cognizant of working with students where they’re at, and again, making sure that we are adaptable enough. And that we provide the resources that are necessary for everyone to succeed,” McLeod shared.

Ultimately, Seattle U’s core programs are always evolving to try to best serve the school’s mission. In the future, the programs will hopefully become even better and find more ways to minimize issues and serve the students who take them.

Note: While the author of this piece is an Honors student, this article is written with the experiences of other students and faculty in mind and aims to be as objective as possible in descriptions of both programs