There is art in the physical qualities of a tattoo: intricate lines that flirt with the contortions of your body, shading etched onto flesh to mimic light and proportionality, symmetry and parallels that speak to grander visions, grander images.

There is art, too, in the intangible qualities of embedding ink into skin.

I was 18 when I got my first tattoo. My best friend and I sat in the lobby of a downtown Salem, Ore. piercing shop, our IDs shaking ever so slightly in our sweaty hands, as we waited to be called back by a middle-aged man with a fiery, copper beard and decades worth of faded iconography extending the length of his limbs.

A small bouquet of daisies on my calf, a single larkspur on her inner arm—we immortalized the beauty of knowing each other with birth flowers and the sharing of a “first.”

It didn’t take long for me to patch my body with more images, now 20 and nine tattoos in. I have grown ever more aware of the manner in which tattoos influence the way I interact with my body, with my sense of self, with society, with others.

My journey with tattoos is a deeply personal one, shifting as the years stretch on and my skin stretches over bone. As ink fades and lines settle, so do the narratives of myself. So do the narratives of others.

Tattoos may symbolize rare moments of intimacy and closeness, just as they may speak of laughter and youth.

Sadie Nelson, a Seattle University third-year history and women, gender & sexuality studies double major, has a mix of professional and unprofessional tattoos, drawing enjoyment from the recollection of getting them.

“I have some stick and pokes from high school on my legs. When I was 15 I thought they would fade in two years, and they haven’t,” Nelson said. “But when I was a teenager, I unprofessionally got a Marlboro cigarette box on my leg– not the best, but it makes me laugh when I see it.”

Just as a story may be born from tattoos, so may visual appreciation. Tattoos, stripped of connotation imposed by oneself or others, are forms of art. An artist using skin over canvas.

Sawyer Dedmon, a content designer at SheMarkets and a San Francisco State graduate, views his tattoos as a medium of art, believing them to stand alone as beautiful images without necessitating profound significance.

“Tattoos to me are just art. I don’t believe they always need to have some deeper meaning. I believe that liking how something looks is a good enough reason to get it tattooed on your body. It’s a form of self expression,” Dedmon said.

While each individual interacts with their tattoos in different manners, there are threads that often weave people’s motivation together. Tess McDowell, a third-year psychology major at Seattle U, highlighted the commonality of certain motives to get inked.

“People get tattoos based on their experiences, interests, loved ones, even aesthetic preferences. It can be a physical representation of the inner self,” McDowell said.

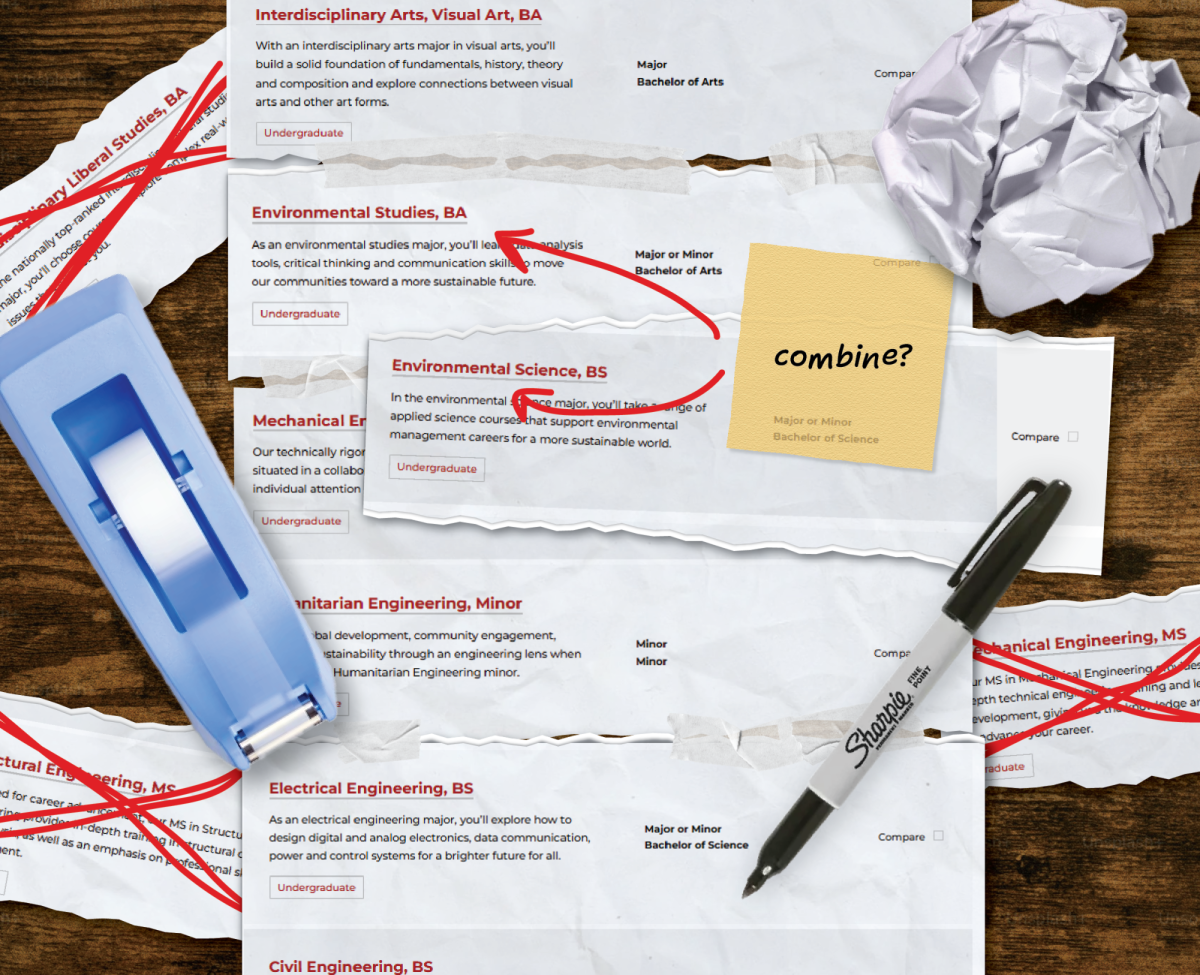

While a multitude of reasons factor into the decision to get a tattoo, some of the most profound understandings are discovered after leaving the artist’s chair. For third-year Environmental Studies and Spanish Double Major Joylyn Golondrina the meaning of a tattoo can change once leaving the chair as well.

“I have a big ol’ tree tattoo on my arm, that I intended to be dainty and I intended to be a representation of me moving to Washington and beginning to develop a relationship with the state and the city of Seattle and all of the wonderful people I’ve met here, but the tattoo artist wasn’t very happy to do the tattoo. It turned out to be something way bigger than I expected or wanted, but now I love it…it’s far more unique than any dainty tattoo I could have gotten,” Golondrina said.

I have often felt separated from my body. That my flesh was not comprehensive of all the depth and dreams and mistakes and worries and loves held within the width of my heart. Tattoos helped to ground me in my physical self. For me, tattoos are a reclamation of my body, a proclamation of self-expression and ownership.

For Ryan Nimmick, a third-year social work major, many of their tattoos are matching to a friend or family member. If not, Nimmick gets tattoos of things they love, such as a sloth tattoo on their leg. Tattoos have aided Nimmick in forming a more productive relationship with themselves, as they see representations of people and things they love on their skin.

“My tattoos mean a lot to me because they have also helped how I perceive myself. I am planning a few more tattoos to help with body dysmorphia, and to build a positive relationship with my body, something I am still learning to do,” Nimmick stated.

Similarly, for McDowell, tattoos helped them to work through discomfort in their appearance. While the way in which we connect with our body exists in a fluid nature, tattoos may serve to build confidence.

“I feel like tattoos have really helped me to not fixate on my insecurities when I look in the mirror. Not only that, but I feel a lot more confident about my overall appearance because of my tattoos,” McDowell remarked.

Nelson reflected the sentiments of myself, Nimmick, and McDowell, but placed emphasis on her position as a female-bodied person. She discussed that existing in a female body presents a disconnect in perception— seeing tattoos as an act against this disconnect.

“As someone who is female-embodied, it is really hard to control how others perceive me, and tattoos have been a way to reclaim autonomy,” Nelson said.

Despite the personal nature of tattoos, they are, depending on placement, outward facing. We all have preconceived notions regarding tattoos, even if that notion is near to indifference.

It is not always indifference, however, or positivity. There are long-standing negative narratives that exist surrounding tattoos, disproportionately affecting people of color. While tattoos are becoming more accepted in everyday society, that acceptance is often grounded in one’s outward appearance.

“Because all my tattoos can be covered, I don’t think that I am perceived that differently. It is a lot more normalized to have some tattoos nowadays, so most of my tattoos don’t necessarily make me look ‘unprofessional,’” Nelson said. “I think I also have some privilege in being perceived as a white woman, as my tattoos are automatically seen as aesthetic choices, rather than delinquency.”

As we build a more tattoo-forward future, the personal nature of permanently altering one’s body becomes increasingly important to recognize and support. As much as one’s body is their own, so are the images they needle onto it.

“I definitely see tattoos on other people that I don’t like or question why someone would ever get that,” Dedmon said. “But at the end of the day I always respect that it’s their body and they can put whatever the f*ck they want on it.”

As much as tattoos are a modification of one’s body, they are an expression of self. Tattoos have an innately transitory nature, their meaning and function unique to the body that houses them.

“I am definitely grateful to have gotten tattoos, for how it’s shaped me,” Golondria said.

What may start as a picture penciled onto a limb, may end as a tribute to the human experience. To having a body. To painting your body as you please.

Tattoos transcend their physical nature. More than images: stories. More than ink: identity.