I understand now why people join cults.

I understand now why people join cults.

Standing in the pouring rain, mascara running down my cheeks as my hair clung to the nape of my neck, I listened as street preachers hidden under the veil of nylon umbrellas warned the crowd that Hozier’s music was sinful: full of lust and fornication.

I thought—if consuming Hozier’s music predestines me for Hell—then sinning is merely an act of relenting oneself to poeticism.

And Heaven must have really boring music.

As rain-soaked bodies flooded into WAMU Theater, I lost myself in a sea of worn corduroy and patchouli; woodsy scents and muted florals adding depth to concrete floors and darkly curtained walls. The sporadic murmurs of the crowd created a tangible warmth that faded thoughtfully into the ethereal spirit of Madison Cunningham’s folksy vocals.

Ever so slowly, by fault of my own anticipation, Cunningham’s opening set melted into dimming stage lights and an unpunctuated chorus of dissonant conversations.

After a nameless amount of time (the passing of time is rendered inapplicable when the anxious bouncing of your legs is the only marker of the present), shadows painted every face in the crowd; a deeply blue light creating a cylindrical veil center stage.

A distinctly tall man, frizzy hair and spindly stature, stepped into the indigo glow.

“At last, when all of the world is asleep / you take in the blackness of air.”

The air pressure in the room shifted as a collective inhalation connected the crowd. Images of upturned earth and sickly trees blurred behind him: a canopy of mossy overgrowth framing the stage.

Powder blue lights flooded upstage as the first chords of “Jackie and Wilson” reverberated throughout the room, pressing their vibrations onto my skin.

This is where the recognition of my own susceptibility to cultish entrancement became overwhelming.

This is where the recognition of my own susceptibility to cultish entrancement became overwhelming.

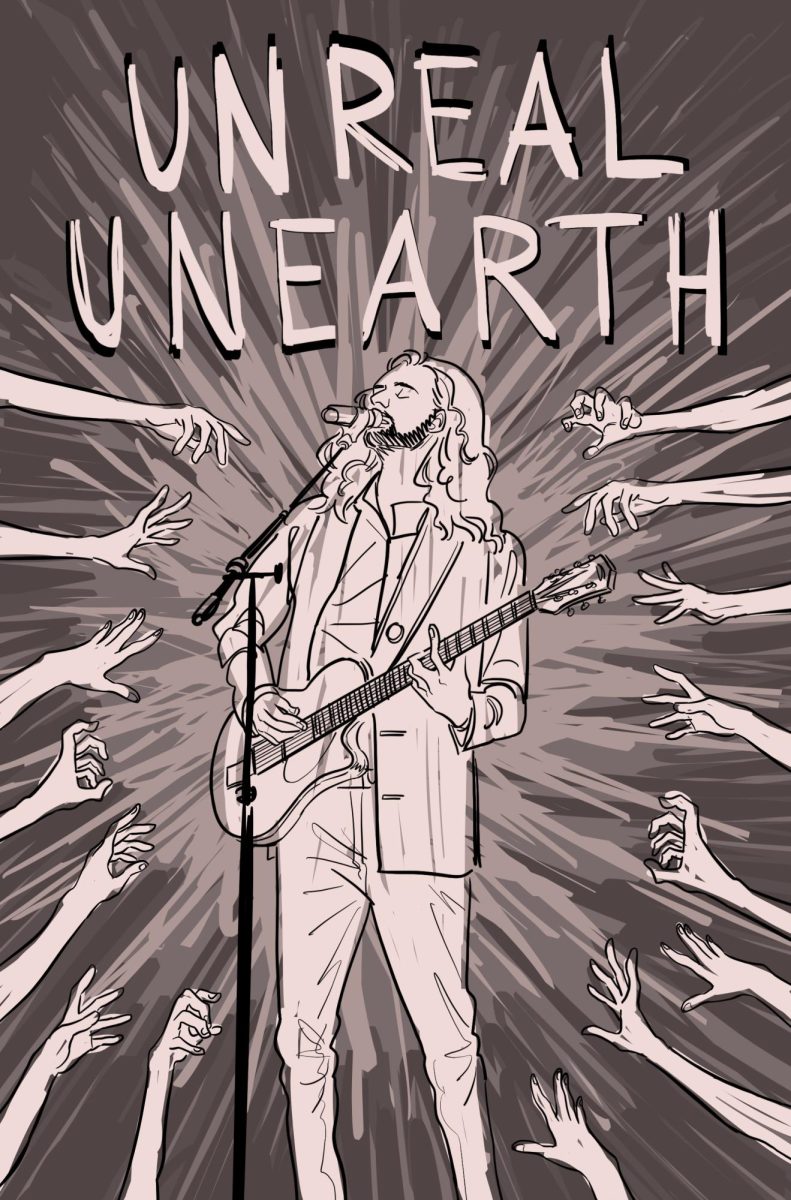

In a room full of chanting people, hands stretched outward towards the pulsing stage lights, drunk on the high of live vocals, I would have followed Hozier anywhere.

I used to struggle to comprehend what leads someone to fall victim to cult influence—what predisposes them and why?

At present, it is entirely clear to me.

You take a person, a man, usually. You give them a way to reach people, to touch them. You give them a platform, a message. And people follow.

An Irish baritone creates songs grounded in storytelling and yearning, stands on a stage and asks the audience to participate in the cultivation of musicality; and I lose any ability to see outside of the present moment, the present movement.

His band leaves the stage, a single stool sat behind a microphone. Acoustic guitar in hand, Hozier rests under red lights as the turbulent energy of the crowd grew gentle.

“It looks ugly, but it’s clean / Oh momma, don’t fuss over me.”

Hozier’s voice, a rich sense of cinnamon and bourbon. The crowd wrapped their arms around each other, swaying on legs they must remember to unlock as not to faint.

Many people still did, to which I hold no blame, what a fitting response to an overflowing of emotion and rhythm.

Once the culmination of songs sung and words spoken indicated the end of his performance, the screen behind him flashed black and white images of queer love, queer torture.

Smoke billowing out under his feet, cascading over dancing heads and into the air, Hozier performed the song that introduced him to the world.

“My lover’s got humor / She’s the giggle at a funeral.”

Following the encore, I funneled out of the venue, heart still beating fast, mind moving slow.

If seeing Hozier live was truly a cult experience or God’s final condemnation of my morality, knowing such would have no bearing over me.

There is something truly spiritual about surrendering your body to music. In the presence of Hozier, this sense of otherworldliness became intoxicating.

Amber

Nov 2, 2023 at 12:59 pm

Yes, Chloe! Yes! You have captured Hozier in words. Seattle was magical. I too kept reminding myself not to lock my legs, breathe. Wonderfully reported. <3