The Complex Legacy Of Washington’s Mysterious Island Prison

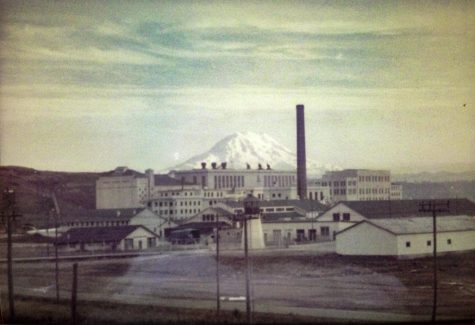

Image courtesy of the McNeil Island Historical Society.

The McNeil Island Corrections Center, previously known as USP McNeil Island.

The following article contains discussion of sexual offenses, including crimes against children.

Situated in the Southern reaches of the Puget Sound, the 6.6 square miles of McNeil Island looks uninteresting, just like any of the hundreds of islands off Washington’s west coast. It’s not immediately obvious that the government owns every inch of it and that boats are not permitted to come within a hundred feet of the shoreline, nor that a prison established there nearly 150 years ago predates not only the federal penitentiary system, but the state itself. Perhaps most unusually, the only residents of the island today are Washington’s most dangerous sex offenders, locked away from the public in a unique legal limbo.

McNeil Island was first purchased by the U.S. government in 1875, and a territorial jail was established on its shores. In 1891, the Three Prisons Act was passed, making McNeil officially a government facility and by some measure the first federal prison in the U.S.. Chris Wright, communications director for the Washington State Department of Corrections (DOC), described the advantages of having a prison that was accessible only by sea.

“It’s like Alcatraz—it’s a lot harder for somebody outside of the walls to get off the island,” Wright said. “It adds another security element.”

Notably though, McNeil Island is huge—thousands of times larger than Alcatraz. Because of the size and isolation, inmates were allowed more freedom than most prisons of the era and were encouraged to learn trades as diverse as leatherwork, shipwrighting and floral arrangements. They existed in close proximity to correctional staff and their families, who lived on the island in a miniature community.

“There was a school, there was a warden mansion,” Wright said. “It was a very unique environment where people were living, working and raising their kids.”

Ann Kane Burkly is the president of the McNeil Island Historical Society and grew up on the island she now works to preserve.

“I lived on the top of the hill and you could look one way towards the Sound and see Anderson Island and Steilacoom and the other side you were looking out at the Olympics. We clammed and fished—anything you can possibly do outdoors,” Burkly said. “There were deer everywhere, coyotes, a bear, a cougar. Raccoons were everywhere because the inmates loved them and would feed them…it was wonderful to grow up there.”

While living a stone’s throw from a prison could have been a dangerous proposition, island life produced a relationship of sorts, even between inmates and the families of correctional staff who resided around them.

“We were never afraid,” Burkly said. “Inmates in some instances were quite kind and protective of us. There’s a code in prison—they don’t like anybody who messes with kids.”

In 1976, the Bureau of Prisons announced that McNeil would be phased out. The prison was old and built to house thousands of inmates, a dinosaur in an era where the prisons were designed to be small, with capacities of five hundred or less. On top of that, the cost of island upkeep was a continual sink on the federal budget. But as the shutdown began on McNeil, Washington was experiencing an overflow of prisoners at the state level, attributable in significant part to the rise of the War on Drugs.

“[The U.S. Government] thought they were going to smaller prisons with Supermax surveillance,” Burkly said. “But instead we had the eighties come along with the three strikes law and prisons grew massively.”

Former Governor John D. Spellman saw a solution in the facilities already available offshore, and leased the island from the federal government in 1981. The facility would stand for nearly 30 additional years as a state prison before being condemned for much the same reason—it was too old, too big and too expensive.

“2008 was one of the worst financial crises in state history,” Wright said. “Large cuts were made everywhere and that’s when it was officially decided that [McNeil] was too pricey.”

With the closure, the small village on McNeil that once held a thriving community was left to fall apart. Burkly, who still returns to the island from time to time, sees her childhood home, schoolhouse and the rest of the island that raised her slowly succumbing to mold and decay.

But that wasn’t quite the end of McNeil Island. The Department of Social and Human Services (DSHS) built another facility on the island in 2004, deemed the Special Commitment Center (SCC). The facility is not technically a prison, but nonetheless patients are not permitted to leave.

Normally, confinement after one’s prison sentence has ended would be a violation of a citizen’s civil rights. But due to a Washington State’s Community Protections Act, passed in 1990, a judge can civilly commit someone convicted of a sex offense to a treatment facility for an indefinite length of time.

Brad Meryhew, a criminal defense attorney and chair of Washington’s Sex Offender Policy Board, described the law as a public health and safety measure.

“We as a society have confined people against their will outside of the criminal justice system for most of our history, for what we deem to be profound mental illness,” Meryhew said. “If somebody is a danger to themselves or to others, or if that person is gravely disabled…the State has the right to take them into civil commitment.”

The isolation of McNeil, which had driven the federal government and the DOC off the island, was almost a benefit as the location of a treatment center for sex offenders. Tyler Hemstreet, media relations manager with the DSHS, pointed out that an offshore facility helped the public feel more secure than mainland treatment by sequestering offenders an ocean away.

“When [SCC patients] are on McNeil, they’re out of sight, out of mind,” Hemstreet said. “And I think community members like it that way.”

The number of people civilly confined at McNeil is not publicly available, though past articles have put the number north of 200. The majority of patients stay at the SCC for decades, with the island also serving as pretrial holding for ex-cons awaiting a hearing on if they are to be officially civilly committed. Hemstreet described an extreme case of a current resident confined at the SCC for seven years, still awaiting his trial. Many of McNeil’s residents will die on the island.

Some will take a different path. If treatment has been completed and a court finds the individual to no longer be a community risk, patients can be released to a stage called Less Restrictive Alternative (LRA), in which they are allowed to return to the community in a limited capacity. Residents of Tenino and Enumclaw have vehemently opposed establishing LRAs in their cities, though Hemstreet emphasized that community risk is minimal.

“They not only have DOC oversight with ankle bracelets and attorneys, but they also have community treatment providers and stable housing. They have intense wraparound services that strengthen community safety and minimize the likelihood of reoffense,” Hemstreet said.

The process of civil commitment has faced ethical and legal challenges. A 2015 complaint lodged by Disability Rights Washington asked the state to make a true rehabilitative effort at the SCC, alleging that many residents were being denied access to therapy that would allow them to make progress towards release.

“The point was made that you couldn’t simply warehouse these individuals,” Meryhew said. “You had to offer them meaningful treatment and opportunities.”

But offering sex offenders rehabilitative therapy and the ability to return to the community is a highly controversial topic. Generally speaking, many Americans believe in a severe legislative approach to sex crimes. Stronger laws and stricter punishments often pass with bipartisan support, and opposition on any grounds can be construed as excusing horrific abuse. Capital punishment is frequently part of the conversation, with a Florida law designed to streamline the execution of certain sex offenders enacted earlier this month.

Meryhew argued that the instinct to enact vengeance on those who have done harm doesn’t always reflect the reality of the situation.

“The truth is, [some long-term SCC patients] are no longer sexually violent predators,” Meryhew said. “We can now say, with some degree of psychological certainty, that these people are not the risk to the community that they were when they were first brought into the system.”

An alternative to the increasingly severe punishments, medical experts are pushing for therapeutic treatment. Fred Berlin is the director of the National Institute for the Study, Prevention and Treatment of Sexual Trauma, as well as the director of the Sex and Gender Clinic at Johns Hopkins University. Berlin has been researching paraphilias for nearly 50 years, and believes that a treatment-focused approach is more effective than a punitive one, even for the most heinous crimes.

“Take the example of someone who’s sexually attracted to children. There’s nothing about prison alone that can erase those attractions or enhance that person’s capacity to resist acting on them,” Berlin said. “The idea that we can punish the problem or legislate the problem away is very naive.

Therapeutic treatment for sex offenders in the U.S. (including the SCC and McNeil Island) is reactive in nature, occuring only after somebody has been victimized. Berlin pointed to a German program, Prevention Project Dunkelfeld (PPD), as a treatment model that hopes to stop offenses before they are committed. PPD guarantees therapy for pedophiles and hebephiles, and is only possible because of unusually strong doctor-patient confidentiality laws in Germany.

“There have been reports… of very significant numbers of previously undetected people coming in, getting help, and doing well,” Berlin said. “We can’t do that in the United States…there are a number of young men who are aware they’re not attracted to people their own age and want help, but the last thing they’re going to do is raise their hands and ask for it.”

For over a hundred and fifty years, McNeil Island has served to punish people who have committed the most grievous wrongs against others. But it’s also been a place of healing and rehabilitation for society’s most downtrodden, with prisoners and patients released better than the island found them. Burkly views McNeil’s legacy as one of healing, not one defined by the horrors of the prison industrial complex.

“You spend a lot of time looking inward and growing [at McNeil],” Burkly said. “People are recoverable if you give them an opportunity and some guidance.”

What comes next for McNeil Island is a hotly debated topic with numerous interested parties. The Historical Society advocates for the preservation of the old prison facilities and the island village that is fighting an onslaught of decay. The Steilacoom tribe claim the beaches as part of their hunting grounds. Real estate moguls are eyeing the undeveloped beauty of McNeil, while the Department of Fish and Wildlife works to return the island to its natural state.

In the meantime the DSHS continues to operate the SCC, hoping to find recovery and restoration for a population reviled by policymakers, healthcare officials and the public.

“There’s not the sense that the people that are out there at McNeil Island are human beings deserving of help,” Berlin said.

Terry Akins

Jan 11, 2024 at 1:59 pm

There is a happy medium there. I gaze at the island from my home every day and wonder why we have set aside such a valuable asset for so little gain. The efforts of the state to rehabilitate the “residents” could continue to take place within a more developed environment. The idea that we must separate ourselves just to provide security really doesn’t make sense. Hopefully, the future will see a legislature with a more imaginative approach.