Public Safety Addresses Community Concerns Following Shelter-In-Place Scare

Text notifications from Seattle University Public Safety.

On Feb. 16 at 4:08 p.m., Seattle University’s Department of Public Safety sent out an alert to students regarding police activity in the Broadway Garage.

Some students and staff got the alerts, some did not.

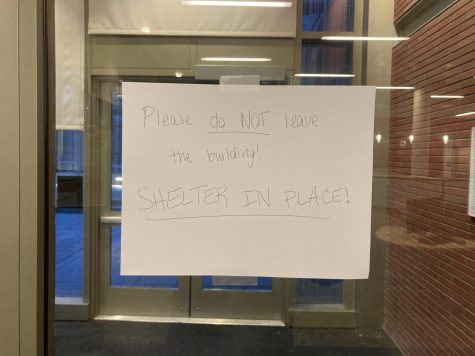

As the campus initiated a shelter-in-place at 4:11 p.m., text messages were sent to those enrolled in the alert system. Those who did not have text message alerts enabled found out from other students, resident assistants and staff alike that there was a serious situation developing on campus.

By 4:29 p.m., every building entry on campus had been locked due to the armed carjackers police were searching for on campus. Eventually, the situation was resolved, and the shelter-in-place order was lifted at 5:16 p.m.. Outside of the initial incident, which occurred off-campus, no one was harmed, but the saga did not end without its fair share of confusion from the community.

Some students and staff were locked out of buildings, clueless as to why that was. Others received the messages in class and had to stop their lectures to share the news, like Fourth-year Finance major Jay Grant.

“My professor had no idea what was going on while we were in class,” Grant said. “I had to tell our professor that we were in lockdown, but nobody knew what lockdown actually entailed.”

Grant’s class continued on as usual, even with a police loudspeaker blaring outside. That is until the police arrived at their classroom and spoke with the professor, clarifying the non-routine nature of the situation.

Second-year Environmental Studies major Benjamin Conroy did not have the text message alerts enabled and was on campus near the site of the Feb. 16 incident. He found out there was major police activity taking place just a few hundred feet from where he was sitting from friends relaying the alerts to him via text messaging. According to Conroy, many of his peers had a similar experience.

“In the library where I was, a lot of people were confused and unsure about what exactly they were supposed to do before the [public announcement system] came on,” Conroy said. “In terms of communication with the students, I think that needs to be improved.”

However, considering the final outcome, Conroy thought the situation was handled well by law enforcement and Seattle U Public Safety.

“In terms of the cops showing up immediately and making sure people were not involved in the incident, that went pretty well,” Conroy said.

Fourth-year Communication and Media major Raul Lopez, who was not on campus at the time, did not have the text notifications enabled. He found out about the situation from friends and peers after the situation was resolved.

“I didn’t find out about it until a few hours after,” Lopez said. “I had to find out from a University of Washington student that it happened.”

Lopez had tried to initiate the text message alerts that first reached students on Feb 16. multiple times. But he alleges that he never received a message from Public Safety, as the system would not activate despite his numerous attempts.

Lopez found the “Timely Warning Notification” emails from Public Safety to be sufficient last year, adding that they gave him a good idea of areas to avoid and were sent on time. As the 2022-23 academic year began though, his views on the email system began to change.

“[The emails] come a lot later than when [threats] actually happen now,” Lopez said. “I definitely don’t have faith in them.”

The events and confusion of Feb. 16 prompted an “after-incident review” of the current notification and training practices of the university. The review yielded substantive changes that were announced in the afternoon of Feb. 22 via an SU Today message from Interim Director of Campus Public Safety Dominique Maryanski. The changes will be implemented in the next few weeks, according to the message.

“All students, faculty and staff will be automatically enrolled quarterly in our emergency alert notification system, which includes text, desktop and email delivery…,” the statement read.

Notifications will now include specific instructions on what to do for staff and students in the case of an event, such as in a shelter-in-place.

This kind of detail-oriented notification system is something Seattle U Professor of Economics Meenakshi Rishi would have appreciated. She had text notifications enabled but the brief nature of each was not specific enough for Rishi. She noted that simple things like whether to barricade doors or hide were not made clear, causing frustration on her part as a professor.

“There needs to be a very consistent message on the texting scheme that says, ‘OK, this is A not B. And when A happens, these are the steps you have to do,’” Rishi said.

The situation was also another example of the spike in crime that has been taking place in Seattle since 2021. After hitting a relative low in all crimes in 2020 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Seattle has seen a serious uptick in criminal activity over the past two years.

Local crime shot up by 10.5% in 2021 as businesses began to reopen and most citizens returned to normal life. The situation deteriorated from there, as 2022 was the worst year for crime in Seattle since 2008 in terms of total offenses.

With the gravity of the situation and the rise in local crime recently, the Seattle U community came to collectively realize the importance of a far-reaching and efficient notification system last week. There are already regulations for public safety notifications for Seattle U to meet.

The Jeanne Clery Act requires institutions of higher education to send relevant crime data to the public. Serious crimes including homicide, sexual assault and robbery all fall under the guidelines of the Clery Act. Crimes such as these require universities to send out “timely warning notifications” to community members in real time for the sake of public safety. This means alerting community members as to what has occurred, what areas to avoid and more relevant information.

However, the Clery Act does not specify the manner in which this info is to be disseminated. It does not contain language regarding what medium a timely warning must be shared in, meaning individual institutions have differing processes. Seattle U uses email alerts and text message notifications which students and staff need to sign up for.

Crimes which occur near campus also fall under the regulations of the Clery Act. The official Clery Center website lists “public property immediately adjacent to the campus” as a viable location to consider sending out a timely notification. Considering Seattle U’s small campus size, the university also has to account for incidents near campus.

The most recent timely warning notification sent out due to an off-campus incident was Jan. 8.. An unnamed Seattle U affiliate was assaulted at The Chieftain Irish Pub and Restaurant just after 2:00 a.m.. The timely warning notification for the event came almost three full hours after the situation was resolved. The email noted what had occurred and provided guidance.

“Use your intuition and trust your feelings. If you feel that a situation is not right, move out of the area immediately,” the email read.

Although that situation seemed to be isolated, the email was sent as a “timely warning notification,” which is a designation reserved for ongoing safety threats.

This inconsistency is something some students find frustration with, including Third-year Social Work major Alexis Miller. Miller recalled instances in which the timely notifications and response from public safety were inadequate in her view.

Miller described a time when a friend of hers had their bag stolen during the afternoon in the Sinegal Building, only for the corresponding timely warning notification to allegedly not arrive until hours later in the evening. Miller also expressed concerns about response times, and described a time in which her friends felt threatened by an unfamiliar individual and called Public Safety. Their arrival, which allegedly didn’t occur until 30 minutes later, was disheartening to Miller and her friends, as they felt the situation could have deteriorated in that time.

“I don’t think they’ve done anything to make me feel safer, to be honest,” Miller said. “If I was in a real crisis, I wouldn’t call them.”

While the university has acknowledged the concerns around Public Safety through their email updates to the Seattle U community, there is still a level of skepticism from students and staff. Whether these changes will pacify this tension is unclear.

Dominique Maryanski, interim director of Public Safety, was unable to be reached for an interview with The Spectator for this article.