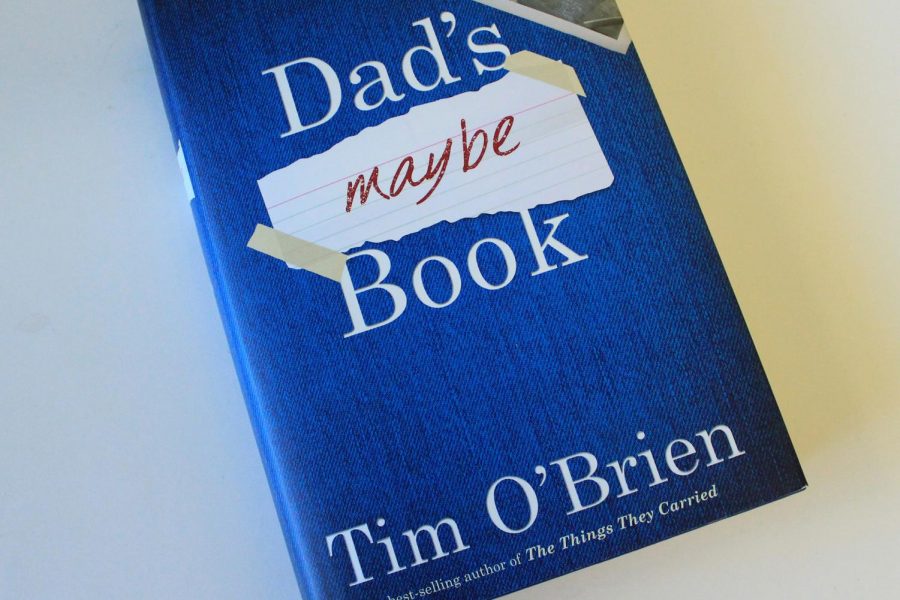

Tim O’Brien Discusses the Power of a Maybe in “Dad’s Maybe Book”

“First of all, aren’t we lucky to get this guy in Seattle?” Adrianne Harun asked the packed reading room in the basement of Elliot Bay last Thursday. Author Tim O’Brien was the guest of honor that night, although if you were to ask the audience members themselves, they would tell you it was an honor just to be in there with him. While O’Brien is best-known for his writing on the Vietnam war— specifically “The Things They Carried,” a work still taught in high school and college to this day—he was there to talk about a different subject matter: his two boys, Timmy and Tad.

“Dad’s Maybe Book” is a work of non-fiction that O’Brien assures is not a parenting book. Rather, it originated as a way for O’Brien to show his kids the real him, the younger him—not the man sitting in front of everyone with “hearing aids, gray hair, and wrinkles.”

O’Brien says the book is the sort of thing he wishes his dad had left for him.

“And, he didn’t,” O’Brien admitted after a long pause.

But credit where credit’s due. O’Brien says that his youngest son, Tad, is responsible for the title and even the formation of the book. While working on the book one day in his study, Tad asked him if he was writing a book. O’Brien told his son no, but when Tad asked, “If you add more pages, then will it be a book?” O’Brien gave that a hard thought and then responded with a “maybe.”

Thus became “Dad’s Maybe Book.” O’Brien joked that he still owes his son $10 for this.

The meaning is more significant, however, as O’Brien expands upon in the book. Life is full of “maybes,” and he relates this specifically to his time in Vietnam.

“Every step was a maybe step,” O’Brien said.

With landmines canvassing the ground, this sentiment is very literal. Every given second, every hour, every year is a maybe.

“Life is fragile, hearts go still, biology is impeccable,” O’Brien said. For this reason, he wants his boys to have fragments of him left around when he inevitably passes—fragments that depict the younger Tim O’Brien, the son Tim O’Brien, the war veteran Tim O’Brien.

The father Tim O’Brien wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for a long conversation he exchanged with his current wife when they were just dating. They broke up for a couple of weeks because she wanted kids. O’Brien did not.

They met up at a restaurant and talked for at least six hours, O’Brien recounts. In that time, O’Brien came to the realization that he did want a family—just not the type of family he’d grown up in.

O’Brien does a good job of explaining life with an alcoholic father. His father was his hero at any given moment when he was sober, but a completely different person drunk.

“My friends would come over and say ‘I wish your dad [was] my dad,’” O’Brien said. “Well, you don’t live at my house.”

O’Brien’s wife also grew up in a fragile home and the two decided they wanted to raise a happy, stable family. They would give their boys the childhood they never had.

In doing this, O’Brien also hoped to instill a variety of morals in his boys. One of those lessons derives again from the root of “maybe.”

“It’s not a sin to say maybe,” O’Brien said. He was fearful that his kids would fall victim to the notion of absolutism.

Even worse, he was afraid they could grow up to become absolutists themselves. Because of these worries, he has always stressed the importance of being okay with admitting that you don’t know something. It’s okay to not be absolute.

“I love my children, but I do not love everything they do,” O’Brien said to echo this sentiment. “I love my country, but I do not love everything it does.”

O’Brien’s ability to be vulnerable not just to his boys, but to a crowd of strangers hanging on to his every word, and even in a book read by thousands, is truly special.

Michelle may be reached at mnewblom@su-spectator.com