“Death by 1,000 Cuts”: The Pervasive Effects of Microaggressions At Seattle U

“The dirty looks on this campus are just—man, I’d be rich if I had a quarter for every single one of them,” Political Science major Kristina Sawyckyj said, reflecting on microaggressions that are present every day at Seattle University.

Seattle U Vice President for Equity and Inclusion Natasha Martin defines microaggressions as subtle, verbal or nonverbal “slights” or “insults,” which can be either intentional or unintentional, conscious or unconscious. Though these acts seem small, Martin said that it’s not the single microaggression—rather, “It’s the death by 1,000 cuts.”

“Oftentimes they are unconscious and they single individuals out or overlook someone or ignore their contributions or otherwise discount individuals or groups based on aspects of their social identities,” Martin said. “It is not the single act. It is the accumulated impact of a range of experiences that one may have.”

As a student with a disability, Sawyckyj often feels unwelcome both when navigating campus and when in the classroom. These microaggressions come in many forms—often, Sawyckyj will ask for help with a variety of things. These requests, Sawyckyj said, are often met with reluctance or hesitancy. “My disability seems to become a burden for other people that I’m around, like going into class every day, the furniture has to be moved because the handicapped desks are always put up against the wall after I leave,” Sawyckyj said.

“It is not the single act. It is the accumulated impact of a range of experiences that one may have.”

“You can see the hesitation like I’m a burden, taking the time to have to repeat ourselves again, and then it makes me feel like I’m not part of the group.” These acts of exclusion can seem minor in the moment, but they have the effect of disrupting the classroom for a significant period of time. Sawyckyj said that oftentimes, it will take half the class period to recenter after a microaggression—time that would otherwise be spent learning.

Another student, who wished to remain anonymous, said that microaggressions sometimes come up during class discussions, when a classmate may say something problematic about their culture. “If they say something off-putting that’s about your culture specifically, and then everyone looks at you like you’re the token person, it feels like you’re put in a place where you want to speak up, but you also don’t want to speak up for other people,” this student said.

For this student, the best way to heal after experiencing microaggressions is to vent to other people of color. The student said that a counselor can fill this role, as well as resources like the Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) or the Outreach Center. Director of the OMA Michelle Kim said that the office’s role is to be a place for students living with marginalized identities to exist without feeling questioned.

“Our work when students are experiencing harm is to be a supportive body, a place for students to come and chat with us about what’s going on—a place to just be and not feel the need to explain themselves, a safe place to land,” Kim said. “And then it’s figuring out what the appropriate next steps are that the student wants to take.” These “next steps” can mean a variety of things—for some students, they may file a report with the Office of Institutional Equity, or they may contact administrators in their respective colleges.

Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) David Powers said that within the college, administrators are able to take a variety of actions to address implicit bias, including microaggressions, in the classroom, depending on who the perpetrator was. If a faculty member is reported for problematic behavior, they may be required to attend specific training before re-entering the classroom, or they may receive a mentorship from another faculty member.

If students are harmed by their classmates, the college may take action to intervene in class. Powers recalled one situation last year where a classroom had been disrupted, and the college brought in a team to conduct a “restorative peacemaking circle.” That specific practice has origins in some indigenous traditions, and it often involves a facilitator, who oversees a discussion among those affected.

Seated in a circle, they would have a conversation about the harm that occurred and how to proceed with the class. The CAS also has a group dedicated to pursuing inclusivity in the classroom. Created in 2015 after the Campus Climate Survey— which measured the extent to which community members felt included or excluded at Seattle U—the Committee for Leadership in Inclusivity and Justice pursues a more intersectional curriculum and a healthier climate in the college.

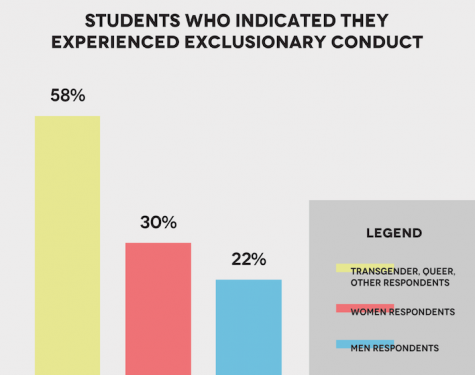

28 percent of respondents indicated that they personally had experienced

exclusionary, intimidating, offensive, and/or hostile conduct, according to a 2015

Seattle U Climate Study Working Group study.

Senior International Studies and Spanish major Michael Ninen serves as a student representative on the committee. “From my personal experience, there are environments in the classroom that can be challenging for students of color and for queer students as well,” Ninen said. “So our goal is to implement some sort of way to record all these types of microaggressions and things that take place.”

He said that at Seattle U, students often overlook the people nearest to them when they talk about the university mission to empower, which promises leaders for a “just and humane world.” “We’ll be talking about some developing country, how they’re going through so-and-so hardship, and the white people in the class will say something like, ‘Oh, we have it so well, we should recognize our privilege,’” Ninen said.

“And I’m, you know, me. I’m sitting in the corner, like, ‘What privilege are we talking about exactly?’” In the Albers School of Business and Economics, the Task Force for Diversity and Inclusion is co-chaired by Professor of Management Holly Slay Ferraro and Economics Professor Stacey Jones. This task force was formed after the Matteo Ricci sit-in in the spring of 2016, during which students voiced frustration at what they believed to be a curriculum that was Eurocentric and misogynistic.

“You can see the hesitation like I’m a burden, taking the time to have to repeat ourselves again, and then it makes me feel like I’m not part of the group.”

This task force has three focuses: competence of faculty and staff in their teaching; the intersectionality of Albers curriculum; and the institutional makeup of Albers in terms of faculty, students, and staff. With regard to microaggressions, Ferraro said that the college has begun offering trainings for faculty to ensure that they are prepared to moderate healthy conversations in the classroom and prevent or step in during microaggressions.

“There will always be microaggressions. I think the reality is microaggressions will exist,” Ferraro said. “So how do we have a classroom where, when those things come up, the professor understands how to manage it in a way that protects the students that are marginalized especially— and also does provide a learning opportunity for students who are like, ‘I had no idea that when I said that, that was offensive.’”

Further, Ferraro said it’s important that students develop the ability to have those conversations past their time at Seattle U, without the facilitation of faculty. Ferraro also said that acknowledging and validating the experience of a student who has experienced a microaggression is crucial.

Citing research conducted by Seattle U Professors Rose Ernst and Angelique Davis, she said that gaslighting can make these experiences all the more harmful. “If you think it’s a microaggression, and especially if you’re a student of color or a woman or marginalized in some other way, then it is a microaggression for you,” Ferraro said.

“To be like, ‘Oh, I didn’t interpret it that way. I didn’t see that happen,’ that intensifies microaggression, because I know something just happened and everybody’s ignoring it and acting like it didn’t happen.”

Though individual colleges, such as CAS and Albers, may be taking action within their individual schools, Martin has been working as Vice President of Diversity and Inclusion to institutionalize university-wide action to prevent and respond to microaggressions at Seattle U.

One of the ways in which Martin has moved forward is through the Bias Prevention and Campus Climate Care Working Group, which she said is working towards the creation of a “bias response protocol.” “We’re balancing the dual value of open expression with creating a climate of inclusion and belonging,” Martin said. “So trying to balance those dual values is a pretty delicate dance. And so developing a bias prevention protocol that can hold those dual values is really important. And I also think it’s really hard to do.”

These data come from the 2015 Campus Climate Project. The project surveyed the Seattle U community, asking a variety of questions including whether they had “experienced exclusionary conduct” on campus.

According to Martin, this protocol should encapsulate both a “reporting mechanism,” as well as a “repair and restorative mechanism.” She said that this protocol needs to prioritize the needs of whoever has been harmed.

“If you think it’s a microaggression, and especially if you’re a student of color or a woman or marginalized in some other way, then it is a microaggression for you.”

In a broader sense, Kim said that she, as well as the rest of OMA, hold the belief that justice that restores the classroom learning environment for those harmed rarely happens after one discussion—rather, she said that it’s a continual process. “Both the party that’s been wronged and the party that is doing harm— [a restorative process means] that neither parties are leaving the classroom feeling alienated, shamed, and retraumatized,” Kim said.

“Justice is a collective kind of experience from my perspective…I think it’s a continued commitment to…righting that wrong and to re-engage in the hard conversation.” This commitment, she said, is a shared respect for each others’ humanity and experiences. In doing so, she said, a community can be empowered to create space for difficult conversations. She also said that while conversations can be grounded in research and study, they must be underscored by empathy.

“To me, racism, sexism and all these isms and biases, it’s not solely an intellectual problem. Certainly, facts and data support and help explain or to convince or to bring weight to the conversation in some ways, but to me it’s not an intellectual problem. It’s an emotional and psychological concern that requires hearts and minds to be moved.”

Josh may be reached at jmerchant@su-spectator.com