During winter quarter, Seattle University’s Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) set out to highlight the ways in which thorough and complete documentation affects historically marginalized communities. The idea came to fruition through one of the monthly “OMA Speaks” events, in which OMA discusses current topics related to identity, diversity, and inclusion.

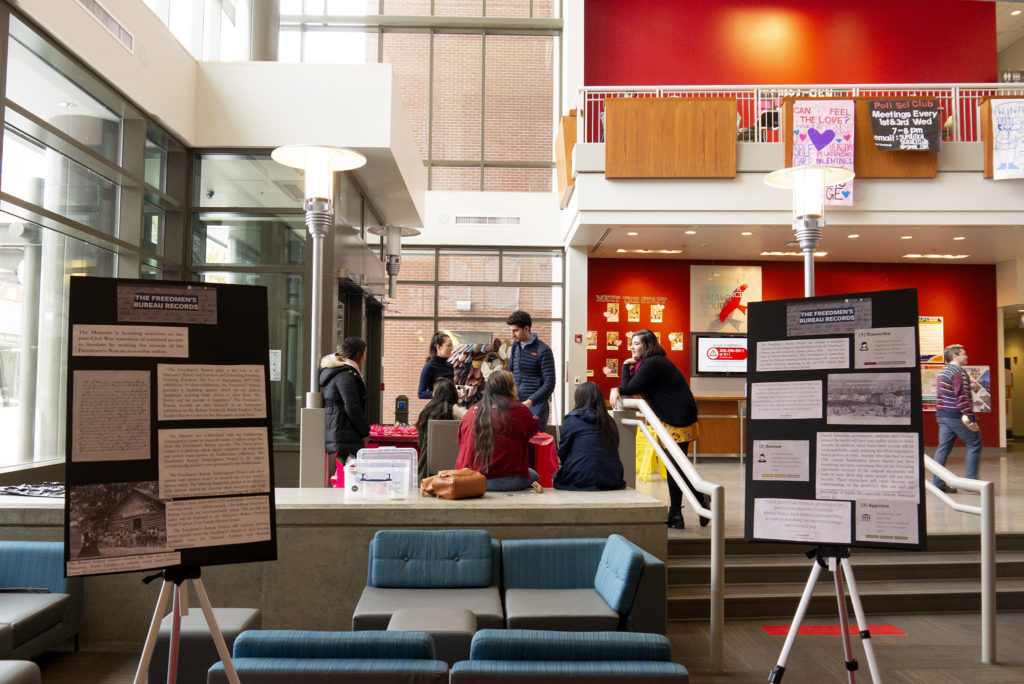

The event was held on Feb. 13 and featured art walls and informational stands erected in the center of the lounge. These historical paper documents made up the centerpiece of the event, highlighting their significance to African American and Native American communities, as well as other marginalized groups.

OMA held a small showcase of the art about the dark past of historical documents of African American and Native American’s in the US.

OMA’s “Documented” series is spearheaded by a graduate Masters of Student Development Administration student Michelle Barreto, who sought to publicize and bring awareness to the Seattle U community about these documents and the groups trying to use them to better educate the public on the U.S.’ history with marginalized communities.

“The point is answering the question of how documentation and paperwork are used and understood in the context of historically marginalized people,” Barreto said.

Barreto said that there are many ways in which documentation can help reveal issues that have existed for hundreds of years simply confined within the pages of a letter, such as slavery, rights of indigenous folks, or incarceration.

For OMA, it is another exciting opportunity to build off of questions that our community has posed. OMA hopes to repeat something like “Documented” in the future, but for now, it’s only set to be a one-time event.

Among those at the event was student Keith Flening, who felt compelled to stop by OMA’s “Documented” event after spotting the “Freedmen’s Bureau” logo on one of the informational stands. Flening described himself as a “Google freak” and had recently discovered the record-keeping project’s website himself while looking for hints of his ancestry on the internet.

“I’m African American, so if somebody could tell me if my great- great-great grandmother was Native American or African, that would be awesome,” Flening said.

For Flening, the Freedmen’s Bureau represents a bridge to understanding his own ancestry, something that in the past was never quite available to him as a result of the oppression that has taken place in our country’s history.

The mission of this particular record keeping project, The Freedmen’s Bureau, is the genealogy piece: to be able to fill out history for African Americans who have had a family past of slavery and oppression. It’s a great way for people to feel more connected to their family and know who their family was in the past, an experience that is typically reserved for white Americans.

Typically, this is a difficult task to accomplish for minoritized communities in the U.S. As a result of the slave trade, native prosecution, and immigrant oppression, the lines are simply not as clearly drawn out as they are for white people.

“How do you trace back your lineage when it was taken away from you on purpose?” Flening said.

This was the very question that OMA felt the “Documented” series would be able to help address through documentation for many other students in a similar situation. They wanted to help make sense of the muddy waters that many non-white Americans are met with when they attempt to look into their past.

The project has already had considerable success. Within just a year of the Freedmen’s Bureau launch in 2015, almost 20,000 individuals have helped transcribe about 2 million records.

The Freedmen’s Bureau has created a platform where anyone can volunteer to help reveal aspects of minoritized communities and families’ pasts through “the Transcription Center.” It functions by allowing individuals to team up online and view these historical documents in their raw form, which they then work to convert into digital documents for all to be able to easily find and search through.

Through this process students could look into both contributing to the online transcribed database or discovering aspects of their family’s history that for years were left unknown.

Student Government of Seattle University President Azrael Howell said that increased access to documentation allows for minoritized communities to explore their family and collective histories, which have been largely hidden due to the U.S.’s racist and violent history with these communities.

“[It] brings significant positive implications for black and African American communities interested in learning more about their past.”

The editor may be reached at

news@su-spectator.com