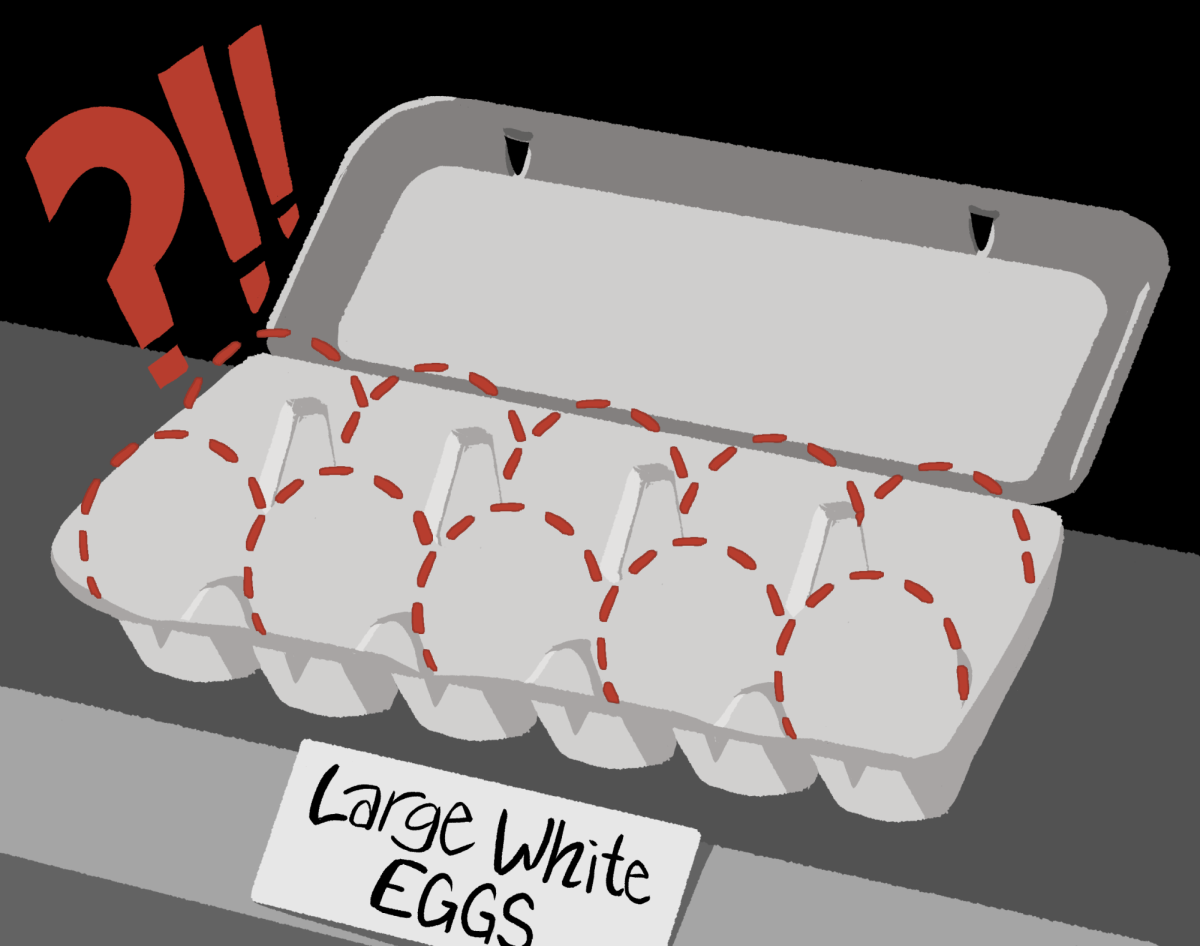

Four weeks ago, a former adjunct faculty member filed a class action lawsuit against Seattle University claiming the school withheld wages from non-tenure track faculty. The lawsuit alleges that adjunct faculty — who are only paid for each class they teach, known as a piece-rate basis — were not paid for work outside of the classroom, such as grading work or developing course materials.

Additionally, the lawsuit claims that the university should have been paying contingent faculty members who teach for more than four hours at one time for a 15-minute break. The lawsuit claims to affect about 200 adjunct faculty members who taught at Seattle U from 2016 to 2018.

“The aggressive money grab is one face, and the other is the stoic, Jesuit face that is humanitarian.”

Seattle U has submitted a change of lawyer notice on Jan. 22, writing that a separate law firm, Perkins Coie, LLC, is going to defend this case on behalf of the university. The lead lawyer, James Sanders, has been the first-chair defense lawyer for several employment lawsuits, including discrimination lawsuits against Boeing and REI.

Though the lawsuit was filed on Jan. 2, Seattle U has only released a one sentence and the university has yet to address the community as a whole. University President Father Stephen V. Sundborg S.J., Vice President and University Counsel Mary Petersen, and former Provost Bob Dullea all declined to comment about the lawsuit and adjunct professors at Seattle U for this article.

Dante Meola, senior sociology major, said that the university’s silence is two-faced between their expensive legal actions against adjunct professors and the values the university promotes as a Jesuit institution, such as social justice.

“The aggressive money grab is one face, and the other is the stoic, Jesuit face that is humanitarian,” Meola said.

The Seattle U mission “is dedicated to educating the whole person, to professional formation, and to empowering leaders for a just and humane world.” Adjunct professors feel the mission isn’t adequately reflecting how the university is handling these issues.

Ben Stork, instructor of film studies, said that the university’s silence is telling in itself.

“It’s important that this refusal to speak on what should—based on the rhetoric of the university—be things that the university is strong about speaking on,” Stork said. “These are questions of justice, of social justice, of what the moral thing to do is. You would think that this institution would be able to make statements about what the moral thing is.”

Seattle U has had a history of litigation surrounding adjunct faculty. The adjunct faculty had previously voted to unionize in 2014, but Seattle U refused to work with the union, appealing their vote to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Eventually, the NLRB ruled that Seattle U was legally required to bargain with the new adjunct faculty union.

That having been decided, Seattle U still did not engage with the adjuncts’ union, citing religious freedom as their reasoning. In a video statement sent to the university community in 2016, Sundborg argued that the federal government’s interference in the affairs of a private Jesuit university was unconstitutional because it infringes on the Seattle U’s ability to live out its religious mission. He said that Seattle U planned to fight the NLRB until the case reached the Supreme Court.

From there, the adjuncts continued to pursue the lawsuit with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) until SEIU dropped it in Jan. 2018. Since then, the fight for unionization has fizzled out, with most contingent faculty feeling exhausted and worn out by the lack of progress and the university’s aggressively non-compromising stance.

Theresa Earenfight, professor of history and director of women and gender studies at Seattle U, believes the university is dragging out this conflict as a deliberate move to weaken the adjuncts’ momentum.

“They are handling it like they really want it to go away, and there are tactics involve foot dragging and stalling and not talking and that is very distressing to me,” Earenfight said. “We technically call ourselves a social justice institution—Dorothy Day was a Catholic social worker. Why is it that everyone in the university administration is really concerned about social justice everywhere but on their on campus? That hypocrisy really bothers me.”

Earenfight said that many of the allegations referred to in the class action lawsuit have been echoing throughout campus for years, and added that she has been involved with adjunct faculty organizing at Seattle U for almost 10 years now.

Stork said that he has been put in a difficult position as an adjunct professor. Recently, he was approached by a student asking him to be the faculty advisor for their independent study. As a part-time non-tenure track faculty member, Stork only gets paid per course taught, therefore Seattle U would not pay him for helping this student.

Stork went to Human Resources, because he was unsure of who to approach for this grievance, and he asked them if this was within his contract. He said that HR told him that advising an independent study would not be covered by his contract, meaning that he would need an additional contract to complete the independent study with the student. Stork said that another contract was never drafted, which meant he couldn’t help the student.

“If you do feel like you are being asked to do more than you’re compensated for, there’s really no pathway to make a protected claim on that,” Stork said. “There is no official person you can go to and say, ‘I think I’m being overworked, what are the standards here? What should I expect to do?’ Then again, it kicks right back into that you’re saying no to students, which is hard.”

In situations such as these, Stork and other faculty are essentially forced to choose between their desire to mentor students with their academic passions and their bottom-line financial needs. Julie Harms Cannon, an instructor of sociology, believes that within this labor conflict lies a greater conflict between Seattle U and the ideals it espouses.

As a Catholic university, professors and administration members aim to impart onto their students Jesuit ideals: a thirst for justice, a drive for social change, and an empowerment of leaders. However, for many adjuncts, including Harms Cannon, the Jesuit mission never empowered faculty.

“If you take that mission and look at it, it’s awesome. But it’s really disheartening to go to work at a place that doesn’t honor that mission with you. Like you have to walk into work and set that aside,” Harms Cannon said. “I know they don’t care about me when it comes to the mission, but it still applies to your own students.”

Stork echoes these feelings about the Jesuit mission.

“It feels more like a brand than it does a mission, more and more,” he said.

However, a group of non-tenure track faculty members are working with the Provost’s Office to craft formal policies to address the concerns of contingent faculty. The Non-Tenure Track Steering Committee was formed in 2018 and boasts nine members that represent all four colleges at Seattle U.

The committee has already implemented two new policies to help address the costs of teaching in Seattle. One is that part-time nontenure track employees will receive 50 percent off parking, or a 50 percent reduction in the price of an ORCA card. Additionally, the committee has worked to create a new non-tenure track faculty fund in the Provost’s Office. The funds can be used for a variety of educational tasks, such as traveling to research conferences or buying books or software to aid in creating a course.

Senior Instructor of Performing Arts and Arts Leadership Dominic CodyKramers sits on this committee. He said that the committee plans to address larger issues in the future, such as raising the salary floor, asking for more transparency around contract renewals, and looking into a formal means of promotion with raises, titles, and multi-year contracts, which will make the process more similar to that of tenured positions.

While CodyKramers is proud of the accomplishments that the committee has completed so far, he said that there is still more to do to address all of the issues surrounding adjunct professors, so he wants to keep the concerns raised from the unionization lawsuit at the forefront of the committee’s agenda.

“We don’t have the bargaining power that a union would have had obviously, but we have the Provost’s ear and he has been very willing to hear us and he understands the institutional issues,” CodyKramers said. “We’re hopeful things will improve.”

Students, along with contingent faculty members themselves, have played a large role in organizing on behalf of the contingent faculty in the past. In 2016, a student club called Reignite the Mission organized the “Death of the Mission” demonstration, where a group of students and faculty marched through campus claiming that the university’s legal action to prevent adjunct professors from unionizing symbolized the death of the university’s mission.

Wendall Tseng, senior political science and Chinese major, has been involved with Reignite the Mission since her first year at Seattle U. Tseng said that students need to create a better institutional memory by becoming involved with campus affairs, and becoming involved early in their college careers.

“There needs to be more people engaged in campus activism because it’s about all of us,” Tseng said. “The universe isn’t going to change their minds, it’s going to have to be forced.”

Tseng spoke highly of Georgetown University’s unionization efforts, where the administration allowed the faculty to unionize after the contingent professors conveyed their distress with working conditions and wages. Georgetown is a fellow Jesuit university, and Earenfight wonders why Seattle U doesn’t follow this precedent.

“Georgetown really set a good example,” Earenfight said. “My mantra throughout all of this is why can’t we be like Georgetown? What is wrong here? And that falls on completely deaf ears.”

Anna may be reached at

akaplan@su-spectator.com

Noah Stepro

Jun 21, 2019 at 1:37 am

This is my reality:(

The policies seem cruel and greedy

Susan Lord

Feb 11, 2019 at 2:52 pm

I work at Kent State University. Several years ago, I directed an independent study for a student and was paid nothing. I spoke to several administrators, who offered different reasons for why I would not be paid. I will likely not agree to direct such a study in the future.

Jack Longmate

Feb 3, 2019 at 9:36 pm

First, a wonderful piece of writing/reporting. I also commend the SU faculty and students for having the courage to speak out. Here’s my best wishes for success of the class action lawsuit about withheld wages. Since adjunct instructors must satisfy the same credential requirements as tenured instructors, teach the same students and award the same grades and credits as tenured faculty, and have the same tuition charged for their classes, they surely deserve equal pay.

This class action lawsuit would not be the state’s first dealing with the treatment of adjunct faculty. The two Mader v. State class action lawsuits dealing with retirement and health care for adjuncts in our state’s community and technical colleges were settled in 2002 and 2003 respectively–for about $12 million each. Now every adjunct in the state’s system who teaches at 50 percent of full-time for two consecutive quarters qualifies for those benefits.

Seattle University is not alone in claiming to be dedicated to social justice and humanitarian treatment of others, on the one hand, while blatantly denying equal pay for equal work to non-tenured instructors on the other. Many of those who advocate free college tuition seem uninterested in paying those who deliver that instruction a living wage. As an adjunct instructor at one of our state’s community colleges, my annual income for teaching at roughly 66% of a full-time load is just over $20K annually.

Jack Longmate

Adjunct English Instructor

Olympic College, Bremerton, WA

Marlene Perrin

Feb 2, 2019 at 12:51 am

My community college: No pay raise for 8 years or so. No pay for prep work except 30 minutes when you are expected to be in the classroom early, but I call that organization time. No pay for prep time or grading, etc. outside the classroom. No separate office; adjuncts must share one room for office space. No support from the administration although there are many, many people employed in administration. Have applied for part time related jobs at the college to supplement the income (most I am qualified or overqualified for) and never even get an interview although HR says that, as an employee, I am supposed to at least get an interview. Job applications are sent to an outside website (to show fairness!) . Now teaching for three institutions at different locations. Was denied unemployment over the summer of 2017 and also in my appeal to the referee because of “reasonable assurance’. I take every course I can all year round, usually offered just before scheduled starting dates, but some have cancellations at the last minute if there is insufficient enrollment, especially in the summer where enrollment seems to be going downhill. By the way, they called all of my employers to check on my employment, which is embarrassing. in the summer of 2017, I was refused unemployment compensation and was also refused on appeal. One of my employers thought that I was quitting because of the call from the unemployment office, and I thought that they weren’t hiring me back. As a result, I lost three months of work for them in the fall of 2017 until the misunderstanding was cleared up. Last summer (2018), I didn’t even try to apply for unemployment compensation because of this situation. Both summers, I lived off credit cards basically. Read the federal Unemployment Insurance Letter 5-17 of December 5, 2016.