The Magnuson Park Gallery was nearly silent last Friday, save for an occasional chuckle. Much of Seattle’s deaf community filled the gallery to support the Deaf Spotlight, who was hosting a group art exhibition to highlight deaf artists.

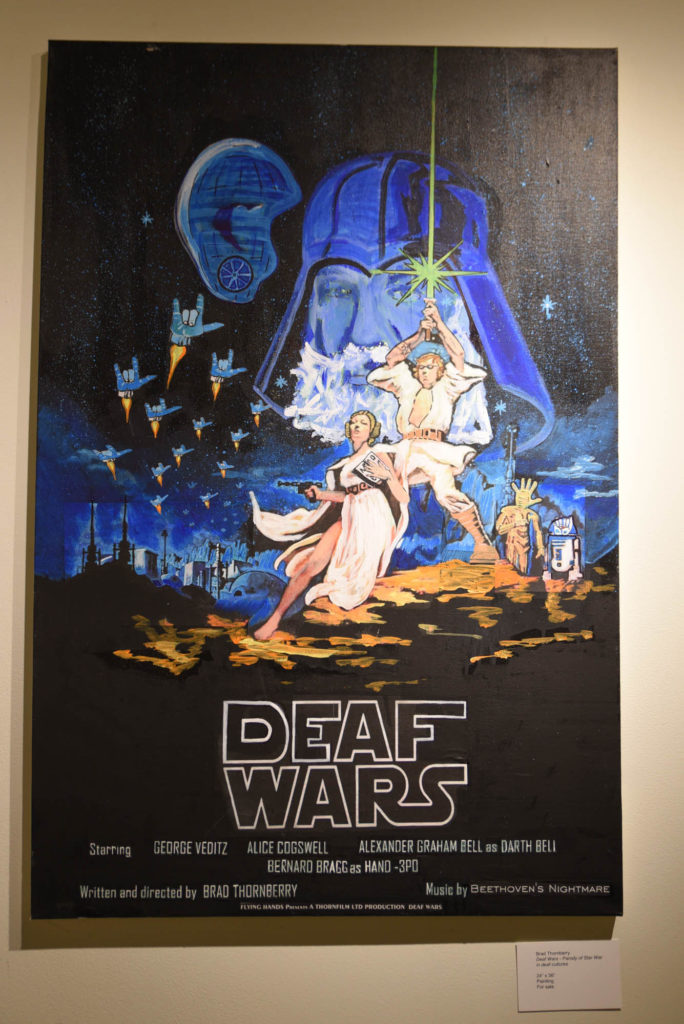

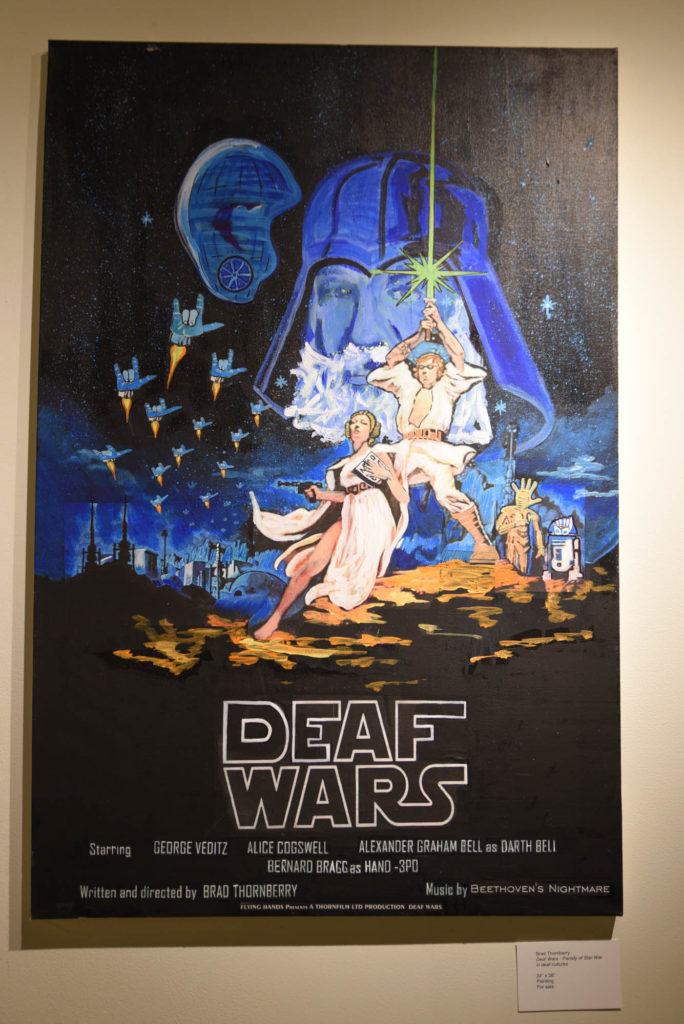

The art ranged from photographic landscapes of Rainier to oil paintings of jelly fish and movie posters reimagined by the artist Brad Thornberry, like “Deaf Wars- Parody of Star Wars in deaf culture”, and “HANDS- Parody of Jaws”, which displays hands forming a sign replacing the shark in the classic movie poster.

Brad Thornberry’s piece, Deaf Wars- Parody of Star War in deaf cultures.

Jasmine Wilson, a student who spoke a small amount of sign language, came to the gallery to learn more about Seattle’s deaf community.

“The art is beautiful, and a look into the culture of deafness. I learned a lot about the deaf perspective on popular culture, and the artists here are truly talented,” Wilson said.

Many of the pieces referenced the genocide of deaf culture, and the diminishing ASL-speaking population. In Thornberry’s collage “Deaf Culture Genocide-the reality of doom for deaf culture,” he pasted headlines about ‘curing’ deafness over a painting depicting people in two lines, one to join the deaf community, and the other to receive a cochlear implant.

Cochlear implants are a device that electrically stimulates auditory nerves damaged in born-deaf infants. They’ve created a controversy in the deaf community.

Jacquelyn Brown, a University of Washington communications student, and CODA (Child of Deaf Adult) explained the phenomenon of deaf culture genocide depicted in the art.

“ASL is its own language. It has its own culture associated with it like Italian or Spanish. Generally people with cochlear implants don’t use ASL to communicate, they use English, so the ASL speaking community is decreasing,” Brown said. “It’s a similar construct to telling Italian children to speak English. It’s the idea of a homogenous language creating a homogenous culture.”

Jacquelyn Brown acknowledged that this is a personal and tough moral decision for parents.

“The conflict is, do you want to give your child the best and all the opportunities? But the other side of that is that being deaf doesn’t take away any opportunities, my parents are college graduates and fully capable. It’s hard for deaf people to stomach because it’s this idea of ‘you’re broken and we need to fix you.’ It’s the struggle between idealism and realism,” Brown said. “I know what I would do but for people who don’t have exposure to deaf culture, they’re freaked out and all the information they get is from doctors who insist their child is broken.”

This feeling of resentment towards being labeled ‘broken’ by the medical community was displayed in Anna Silver’s and Jim Van Manen’s piece “The Periodic Table of Deaf Culture” which featured a periodic table of elements reimagined to reflect deaf culture.

With Brown translating, Ann Silver explained why she chose to depict a periodic table.

“I always saw them growing up, and in 2001 I decided to make one for deaf culture for a festival in D.C. 10 years later, and my collaborator Jim Van Manen and I have improved the design. It is my most popular piece and is in the office of the Gallaudet President,” Silver said.

The piece is color coded, with bright yellow being the heart where Deaf, Deaf-Blind, Hard-of-Hearing, Late Deafened and CODA sit. The deaf identity fades out in color, until the black elements on the perimeter, where Deaf/Mute, Eugenics, and Cochlear Implants in Babies sit.

“The black elements are not really connected to the others, but it is important to recognize that these negative components are still part of deaf culture.”

Another element in black simply said AGB, which Jacquelyn said stood for Alexander Graham Bell. In the “Deaf Wars” poster, Alexander Graham Bell was casted as ‘Darth Bell’ and he also made an appearance as the swimmer about to be attacked in the parody “Jaws” poster.

The art at the gallery contributed to a dialogue that the deaf community is sharing in about a profound sense of erasure, and many they resent the contemporary notion that their deafness is something needs to be “fixed.” These artists used their medium to communicate deaf-pride and educate the community on their lives and experiences.

Quinn may be reached at

qferrar@su-spectator.com

Brad Thornberry

Feb 4, 2020 at 3:18 pm

You have opened the door for me to show around the world someday. Thanks man