Last week the House approved a bill that requires amateur sports organizations to report alleged abuse, including sexual abuse, to law enforcement within 24 hours.

The legislation passed overwhelmingly 406-3, and requires training for coaches and other officials in sports organizations on how to better prevent sexual abuse. The bill follows bipartisan calls for changes in the handling of sexual abuse at the amateur level.

The bill amends the Ted Stevens Amateur and Olympic Sports Act, which governs amateur athletic organizations, and requires them to report sex-abuse allegations, though not in a specified timeline. It also develops new procedures for the U.S. Center for SafeSport, like an easier mechanism for complainants to report incidents through.

A similar legislation led by Senator Dianne Feinstein passed in 2017.

“Sexual abuse is one of the most heinous crimes and our legislation will finally ensure that adults who are responsible for the safety of millions of young athletes will be held accountable for preventing abuse and reporting any allegation of abuse,” Feinstein said.

The new legislation comes on the heels of the trial of Larry Nassar, a former Olympic gymnastics physician. Over 130 women accused Nassar of sexual assault – most being minors at the time of the incident.

In the wake of Nassar’s trial and the #MeToo movement, the NCAA is now requiring athletes, coaches and athletic administrators to complete annual sexual violence prevention education. A committee tasked with solving campus sexual violence issues recommended the new policy.

Last week, the athletic department and any student athlete who wishes to be eligible to compete had to complete an online training seminar on sexual assault.

All the athletes at Seattle U were required to complete a NCAA mandated online training seminar on sexual assault

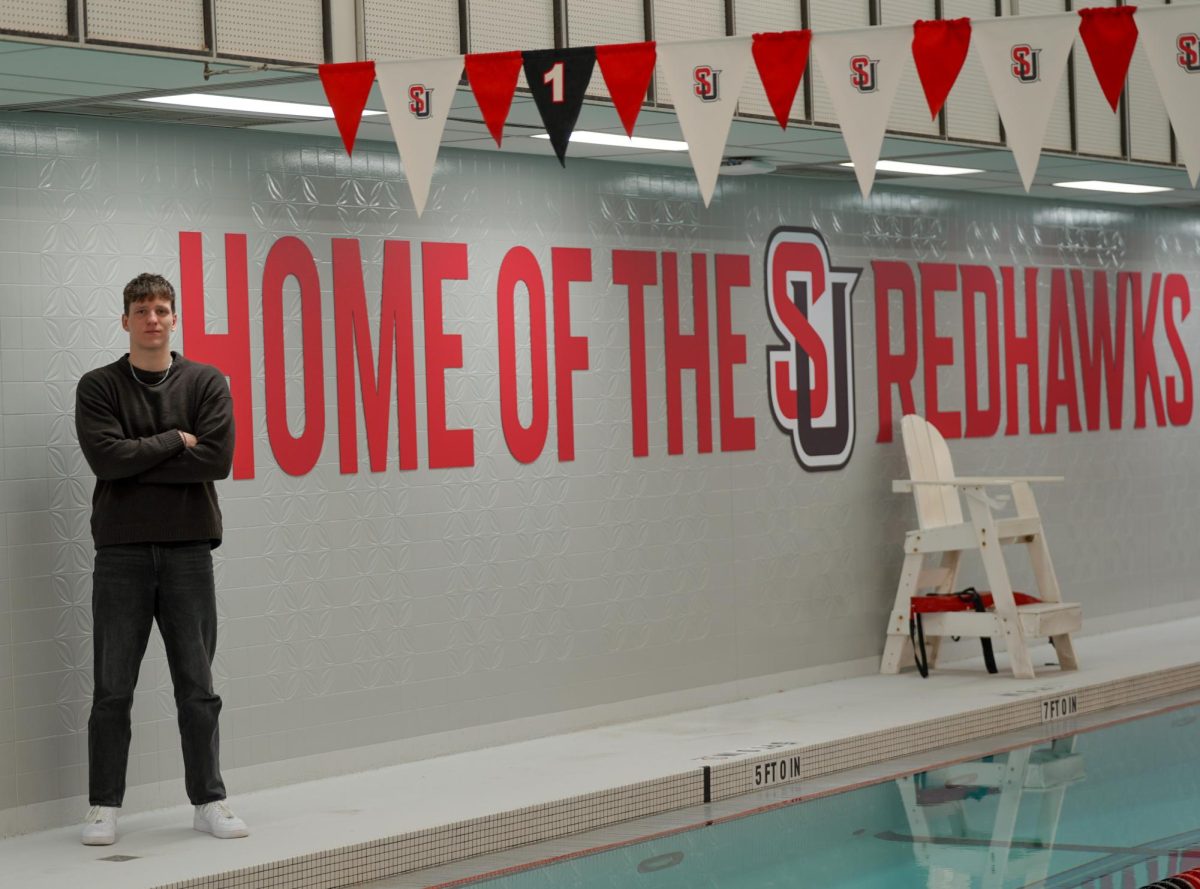

Paige Treff, a swimmer and Criminal Justice/Psychology double major completed the 45 minute sexual assault prevention training last weekend.

“Swimming is a sport where athletes wear very little clothing. Similar to gymnastics, though less hands-on, we are in a vulnerable state during practice,” Treff said.

Treff believes the prevention training will be helpful because it not only defined certain gray areas, but also recommended techniques for interventions in a team situation. She says that sexual assault on campus is rarely talked about in an athletic or team context.

“This year was the first time we’ve had to complete a training like this. It was very comprehensive and included hazing and bullying. I feel that Seattle U often dances around the point, and that they’re just checking a box when they talk about resources,” Tre said. “However, this NCAA training very directly addressed sexual assault, harassment and stalking.”

Rower and Interdisciplinary Studies major Katherine Ollenbrook agrees that the training is a step, but that the school could do more.

“There’s a lot of information missing about Seattle U resources for victims of sexual assault. Sure, CAPS[Counseling and Psychological Services] is an outlet, but it can take months to get an appointment, especially if it’s your first time,” Ollenbrook said. “The school’s resources need to expand to serve our growing student body. Students usually don’t know their legal rights in these cases, and the tension between sexual assault and the Catholic institution where all things sex- related are considered bad makes the administration seem more like an enemy.”

Both Treff and Ollenbrook considered the NCAA mandated online training to be a Band-Aid solution to a larger issue, and that real sexual assault prevention training like the sessions offered by the student- run campus group Green Dot, would be much more effective – as would in-person team talks about assault.

Assistant to the Executive Vice President and Assistant University Counsel David Lance emphasized Seattle U’s commitment to the protection of all individuals. According to Lance, the athletic department and all Seattle U departments are beholden to follow Washington State laws that require the reporting of suspected abuse of minors.

Recently, signage about sexual assault and harassment resources were posted in bathrooms around campus. Along with the new NCAA mandated prevention training and the federal legislation, a cultural shift and burgeoning social awareness of sexual abuse are informing new institutional policy.

But as Ollenbrook puts it, “these are reactionary measures to a phenomenon that has always been present.”

Or in Treff’s words, “awareness is growing and things are getting better, but the resources aren’t enough for everyone, and Seattle U is more concerned about covering their own ass, including forcing complainants to go through the Department of Public Safety instead of the SPD.”

Orion Schade, a Public Affairs major and former rower says that Seattle U could be doing more.

“I’m glad the student athletes are getting trained on sexual assault prevention, but non-athletes need awareness too and the same resources should be available to them. It’s on the student body to prevent assault, and knowing how to intervene at a party or even on the street could save someone,” Schade said.

Whether stemming from current events, better social awareness or growing demand, the NCAA’s requirement and the bipartisan legislation are steps forward in sexual harassment prevention.

Quinn may be reached at

qferrar@su-spectator.com

![All My Favorite Soccer Players Are Retired [OPINION]](https://seattlespectator.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-05-at-20.37.13-1200x783.png)