“We’re in real trouble,” Chris Paul said over the phone on Monday. “Running SU costs more money every year, and we’re making less money every year. That’s a crisis.”

Paul is an associate professor of communication and journalism in the College of Arts and Sciences. He’s also President of the Faculty Staff Senate, a shared-governance body comprised of 11 faculty and staff members. Evidently, he’s not alone in believing that Seattle U is experiencing what some are calling a budget “crisis.”

The Faculty Staff Senate (FSS) gathered for its spring plenary meeting on Tuesday, May 9 where they discussed, among other things, deepening concerns over the questionable working conditions and compensation of faculty and staff and rumored budget cuts in colleges across the campus.

Some of these concerns were alleviated, and others not so much, when President Fr. Stephen Sundborg, S.J. announced last week that the university’s fiscal budget for 2017-18 had been approved by the Board of Trustees.

“As it gets increasingly outrageous to live in Seattle, our wonderful location becomes an area of concern. For a college that has some of the lowest salaries across the board, we’re going to be the canary in the coal mine.”

– Chris Paul, President of the Faculty Staff Senate

The new budget, which reported an increase in net revenue alongside the elimination of multiple staff positions, will serve as a barometer for how the university will weather the changing landscape of higher education in the coming fiscal cycle.

“You know, I’m 60 years old now. I don’t get surprised as easy as I used to,” said Connie Kanter, Seattle U’s Chief Financial Officer and Vice President for Finance and Business Affairs, as she pointed out key parts of the new budget.

Seattle U accrued $213 million in net revenue—$3.3 million more than the last fiscal year—85 percent of which comes from tuition and fees.

Undergraduate enrollment is down due to a large number of students graduating in June; faculty salaries, on average, increased by 1.8 percent but expenditures remained steady across the board.

“It is important to keep in mind that Seattle University is in a solid financial position with stable enrollment overall and continued revenue growth,” Sundborg wrote in his announcement.

“The budget gap for FY18 made for a uniquely challenging process. More than ever, it called on us to engage deeply within and across the university community on the challenges and opportunities before us,” he said. “This type of engagement, collaboration and shared responsibility will be important as we continue working to reposition the university financially and more fully align our education for students with emerging workforce and societal needs.”

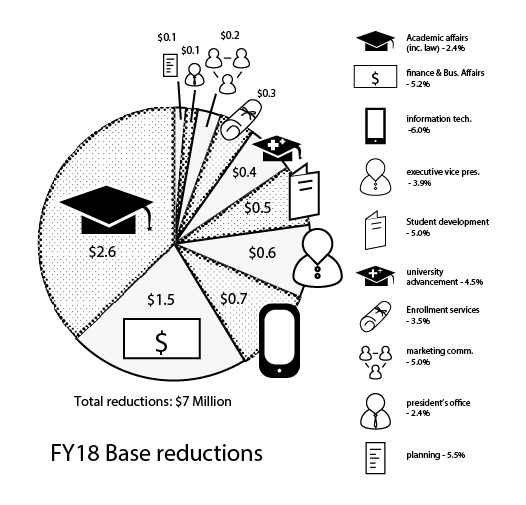

$7 million—or 3.5 percent—in reductions were made in the new budget. $2.7 million came from operational expenses, 2.4 percent from staff related costs, 1.1 percent from program eliminations and reductions and 0.8 percent from contingencies and unused funds from the previous fiscal cycle.

Programs that face elimination and reduction include, but are not limited to, Learning Communities, the Eastside campus, Campus Ministry programs, managed study abroad programs, games at KeyArena, Sullivan program support, summer fellowships, the Center for Jesuit Education, the Poverty Education Center, the Center for Environmental Justice and Sustainability and Athletics, which includes marketing costs, travel fees and coaching staff salaries.

New investments included an added $5.7 million in financial aid, higher compensation in the faculty wage pool and new academic programs like master’s programs in social work, business analytics and mechanical engineering, among other programs.

The budget could be seen as a sign of encouragement. Sundborg wrote in his announcement: Seattle U is in a “solid financial position with stable enrollment and continued revenue growth.” The budget “reflects university priorities” of improved collaboration and shared responsibility, and demonstrated “unprecedented communications and budget transparency” and a “commitment to longer term financial planning in conjunction with [a] new strategic plan.”

“The success of the new five-year plan will depend on our ability to better address issues such as compensation increases and the substantial cost-of-living increases and challenge of finding affordable housing in Seattle,” Sundborg wrote in his letter. “Funding priorities included compensation increases and hiring additional faculty in areas of growth.”

According to reporting done by the Spectator’s news editor Tess Riski, a survey taken by faculty in the College of Arts and Sciences paints a different picture. The FSS created the survey after members encountered and spoke with faculty and staff members who were experiencing financial struggles.

The survey, which was administered to those within the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS), included three questions: what is your position, how long have you been working here and what is your economic reality? 122 individuals—roughly half of the entire college—responded to the survey.

The responses were visceral, but at the same time, not surprising, said Christina Roberts, an associate professor of English and FSS member.

The stories submitted anonymously in the survey depicted an unfortunate situation: professors and employees working multiple jobs, hesitating to start a family for lack of financial stability, others fearing that they won’t be able to support their family, or their children, for much longer.

“When we are not coming together to engage in conversation about the quality of all of our experiences in this space, we can miss important and valuable contributions,” Roberts said.

“Seattle U has incredible opportunities that a lot of these other spaces don’t, but I don’t think SU is looking at those unrealized opportunities,” Roberts added. “Instead they’re looking to what they imagine would be something that would lead to success.”

Roberts alluded to potential partnerships, like the Youth Initiative, through which Seattle U could advocate for environmental stewardship, ending the prison industrial complex and social justice. The university has an opportunity, Roberts added, to help people in need, especially those who have been marginalized like the homeless and those struggling to make ends meet.

“Some of the anecdotes describe people who are clearly in a difficult situation, who are struggling to get by in an extremely expensive, inflationary city,” said Interim Provost Bob Dullea. “It made clear to me that we have a tremendous amount of work to do to find ways to better compensate our people in a situation where inflation is outpacing our ability to grow our revenue.”

Roberts said the survey demonstrates the necessity for a market equity adjustment, a process through which the university tries to compensate its employees competitively by comparing wages to similar institutions.

According to Paul, the last adjustment was done eight years ago, and it revealed that Seattle U was paying, on average, roughly $5 million less in collective median salaries than its sister colleges.

“We need to make investing in compensation for faculty and staff a top financial budgetary priority,” Dullea said. “We need to find ways to grow the university, to increase net revenues, to bring in the funding that will give us the capacity to be better at compensating our people.”

During the last market equity adjustment, Roberts said, Seattle U was compared to institutions like Regis University, in Denver, Colo. and Gonzaga University in Spokane, Wash., among others. Roberts, Paul and nearly all members of the FSS pointed out that neither university is an appropriate model for how Seattle U should compensate its workers.

Seattle U , Paul explained, finds itself in the margins of a wealthy, growing city dominated by massive tech employers—Amazon, Microsoft and Boeing, to name a few—all of which can afford to pay salaries that Seattle U “can’t dream of.”

The cost of living in Seattle isn’t isolated to being able to pay bills. Rather, it spills into all facets of life: “Going out to eat costs more, getting food costs more, transportation costs more,” Paul said. “All those things make being at Seattle U harder.”

FSS members, as well as faculty members who took the College of Arts and Sciences survey, brought forth two major concerns: housing and childcare.

“As it gets increasingly outrageous to live in Seattle, our wonderful location becomes an area of concern,” Paul said. “For a college that has some of the lowest salaries across the board, we’re going to be the canary in the coal mine.”

These issues, he added, affect students just as they do faculty and staff. Paul said that when he started working at Seattle U almost 10 years ago, students could easily find apartments on Capitol Hill in close proximity to campus.Now, he said, that’s not the case.

These problems, Paul concluded, are haunting us now because the university procrastinated.

“We’ve not made hard decisions. We’ve avoided making them and focused on getting from one year to the next,” Paul said. “We have to start coming up with plans and strategies, and those require hard choices that traditionally we’ve not been very good at making.”

Roberts said she believes there’s an additional factor: poverty shaming and the privileging of wealth.

“[Wealth] shouldn’t be something that is causing anyone personal shame when there are inequities—historically, locally, all across the board—that are creating these conditions…and has created a condition in which people who are struggling economically have internalized a sense of shame, and that’s something that I want all members of our campus community to be really intentional about not replicating” Roberts said. “It perpetuates that narrative, that if you just worked hard enough, you’d be successful.”

Roberts believes the shaming of poverty, and the struggles that it involves, will only serve to stifle the conversation and dampen future efforts to address such inequities.

To help, Roberts stocks her office with food and tells her students: “If you’re hungry, come to my office and I’ll feed you!”

Nick can be reached at

nturner@su-spectator.com