Five percent budget reductions are expected to be made across the board over the next school year. While the budget won’t be approved officially until May, Seattle University administrators confirmed that one of the programs to be cut is Learning Communities.

Some say the decision to cut this relatively small program is indicative of the aggressiveness of this year’s reductions, and faculty have said that while the program is problematic in ways, Learning Communities increase retention and help students make connections.

Learning communities, or LCs for short, are known by many students as the different “themes” for each floor in their first year dorms. These communities enable students to live among like-minded peers and to enroll in “linked courses” tied to each Learning Community. The idea behind linked courses is that students can, in theory, take a class during their first quarter of college with students who live on the same floor as them. But this isn’t always executed in practice.

There are 14 LCs, each of which has a faculty director, staff director and one or two student academic mentors.

Kate Koppelman, director of university core curriculum and English instructor, explained that the Learning Communities may not be cut indefinitely, but will at least be on a one-year “hiatus.” During this hiatus, Academic Affairs will focus on improving connections between faculty and first years in a more equitable way.

Koppelman said while she doesn’t necessarily think cutting the Learning Communities is the most effective way to improve them, there are certainly problems within the program that need to be fixed. The Learning Communities program is the child of two parent departments, Academic Affairs and Student Development, and itsroleinbetweenthesetwoareasisnot well-defined.

A faculty member who asked to remain unnamed said Learning Communities are “clunky” and have a “weird architecture” that could definitely be approved upon. But they say taking a break from anything– school, a significant other, a job–often leads to a total breakup. They said they fear the same will be true for Learning Communities: they’ll be put on a so- called hiatus for a year, only to never return. They added that they believe the primary reason the university is cutting LCs is budget-related, not program-related.

Despite the problems with the program, Koppelman said the Learning Communities seem like an odd thing to cut considering their small size.

“I sit on Academic Assembly also, and this was one of the questions that was asked kind of repeatedly…the cost-benefit analysis of cutting something that’s a relatively small percentage,” Koppelman said.

Henry Kamerling, Seattle U history instructor and faculty director for the Justice in a Diverse Society Learning Community, said he thinks cutting Learning Communities “represents an assault on the academic life of the community.” He added that they’re supposed to be designed to promote academic conversations outside of the classroom.

“If you remove Learning Communities from the academic life of the school and the cultural life of students, then you narrow the space for those academic conversations to take place,” Kamerling said. “So that’s unfortunate.”

THE DEPARTMENTAL CUTS PROCESS

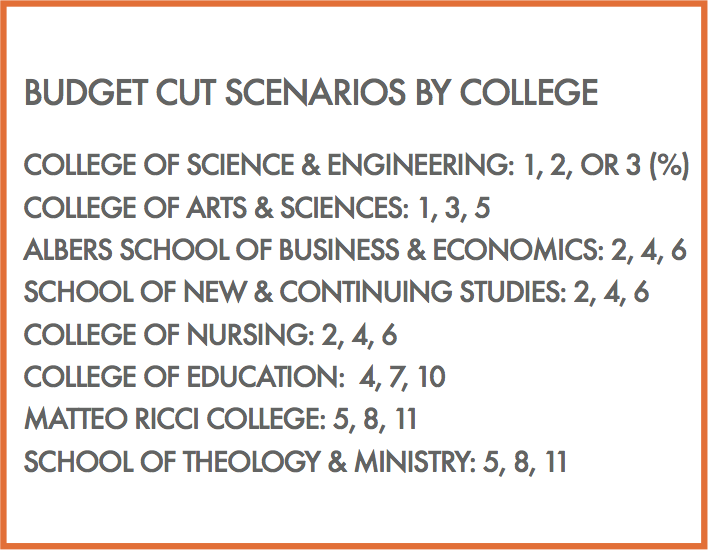

Each college was asked to produce narratives for three different budget cut “scenarios” explaining what results they anticipate happening at the varying cut percentages. While each department is unsure which one of the three will be selected, they are certain it will be at least one of them.

The departments gave their narratives to the cabinet, a group of 12 upper administrators including the president, provost, Chief Financial Officer and various vice presidents. The cabinet will then select and present their budget to the Board of Trustees for approval.

Interim Provost Bob Dullea said that, historically speaking, as long as the Board is presented with a balanced budget, they are pretty likely to approve it. In other words, the Board isn’t doing a lot of deliberating over what cuts to make. Instead, the vast majority of that decision-making process happens in the cabinet.

Dullea said he anticipates hitting at or below the middle number scenario for most colleges. The “targets,” as he refers to them, were decided based on the existing budget size of each college and its enrollment numbers.

“We wanted to assign targets such that, if each area hits the middle number, the division as a whole would be at the five percent target that it has,” Dullea said. “It’s my hope that the division will have to contribute significantly less than the full five percent, so we’ll be able to come in below those medium targets, in most areas at least.”

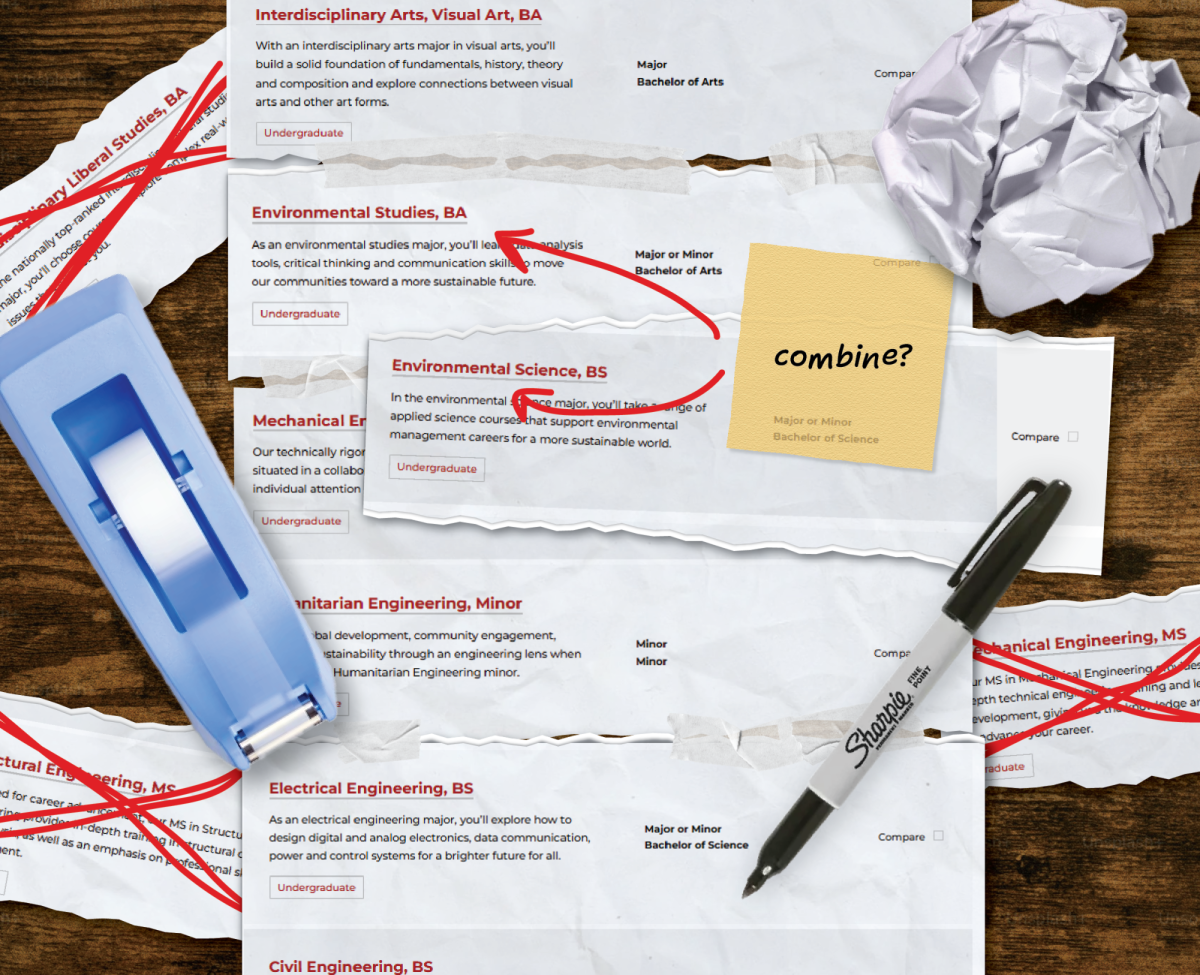

The College of Science and Engineering has seen a massive growth in enrollment over the years–a nationally sustained trend not necessarily unique to Seattle U. It’s a large department, both in size of faculty and students, as well as its budget. Because it’s thriving and has such a large budget already, Science and Engineering was asked to make proposals for cutting 1, 2 and 3 percent.

On the other side of the coin is Matteo Ricci College, an already small department that has experienced significant drops in student enrollment. While low enrollment has temporally followed the sit-in that occurred last spring, it is also true that the college’s numbers have been declining for years. MRC was asked to make the largest budget cut proposals out of all the colleges—tied with the School of Theology and Ministry—at 5, 8 and 11 percent.

Dan Washburn, Associate Dean of Matteo Ricci College, likens a 5 percent cut in MRC to a “belt tightening” for which the college would need to be more mindful of the costs of things like photocopying, office supplies and food.

8 percent cuts, though, he says are more concerning. As for the 11 percent option, he refers to it as both “shocking and awful.”

“Eight is scary and 11 is like, all adjuncts being paid to teach one course. It’s a really kind of cheap solution,” he said. “Quality is sacrificed at 11 percent.”

He said in the 11 percent scenario, instead of hiring full-time faculty to do full-time work, the college would need to pay the bare minimum, hiring adjuncts to teach just one class a quarter as to avoid paying them benefits. The effects, he says, that this has on the classroom learning environment are “not good.”

Unrelated to the cuts, two full-time faculty plan to retire from MRC by the end of the year. Washburn spoke to a nationally-recognized trend called “adjunctification” in which full- time, tenured professors retire and, rather than being replaced by another full-time, tenured professor, part- time adjuncts are brought in to fill their spot.

“But what that means is the person is new,” Washburn said, speaking of adjunctification generally and not necessarily in relation to Seattle U. “They don’t have a feel for the ethos of the place where they’re working. They don’t necessarily understand how their courses fit in with the general curriculum. They don’t have the kind of commitment, they don’t have the skin in the game that a full time employee does… So they have to be thinking about their careers and lives apart from it and that means when a student graduates from an institution, that institution has lost its brand.”

“I AM COMFORTABLE SAYING THAT I DO NOT SHARE THE PERSPECTIVE THAT UNIONIZATION ISSUES ARE DRIVING THE NEED TO CUT MONEY IN ACADEMIC AFFAIRS.”

Bob Dullea, Interim Provost

Unlike core classes that are described by many as “bursting at the seams,” MRC struggles to fill seats and has reduced sections for major requirements. A separate problem is true for the rest of the university.

In the core, classroom cap sizes are expected to increase. According to Koppelman, Module I course caps will raise from 19 to 20 and Module II and III caps will increase from 28 to 30 students.

“I’m unhappy with the cap raises,” Koppelman said, “but I’m not panicked about them, because I do think that an increase of one student in each Module I class does not have as much of a potential to impact how that class is taught.”

She said she would be worried if Module I course caps increased to the mid-twenties, because classe sizes that large could negatively affect the pedagogy.

She said increasing caps sizes limits the number of sections needed to be taught. Effectively, less faculty are needed to teach the courses, saving money. The downside is that less faculty are employed at the university and students have fewer course choices.

FACULTY MORALE AT A NEW LOW

Of the handful of professors surveyed, all expressed a sense of stress or anxiety due to the impending budget cuts. One even referred to the current environment at the university as “depressing.”

“I think the morale is not fantastic,” Koppelman said. She noted that despite the anxious atmosphere, there are many people at the university, some of whom are in upper administration, working hard to improve faculty well- being.

“I have never seen morale like this in my time here,” said Michael Ng, who has taught history at Seattle U for the past seven years. Ng says he knows full-times and part-times who aren’t expecting to be asked back next year.

Kamerling said this budget cycle is particularly difficult in comparison to years prior.

“When you work as an employee during a business cycle that is experiencing retrenchment and retraction, it’s depressing and it is anxiety-producing,” Kamerling said. “It is not a happy environment. It’s a difficult, emotional environment to inhabit because you worry about your future and the future of your colleagues. And I worry about the students.”

While non-tenured and non- tenure track faculty are in vulnerable positions, even tenured faculty expressed worry about job security.

A faculty member who asked not to be named said that while tenured faculty are technically safe from layoffs, they’ve seen instances in which entire departments or programs are cut, subsequently laying off tenured faculty. In other words, professors don’t feel truly safe from job loss in this environment, even with the seemingly iron-clad protection of tenure, the source said.

That same faculty member said in departments all across campus, faculty are “unhappy and scared.” They said non-tenure track faculty have been told they’re losing their jobs, and that they know of professors who expect to be reduced from full-time to part- time and others who expect to lose their jobs completely.

The source said according to Seattle U’s “Fall 2016 Faculty Profile,” available on the university website, over 57 percent of professors are non-tenure track, meaning they’re vulnerable to layoffs at any time. In addition, they said, full-time faculty often don’t know until summer whether or not their contracts will be renewed for the next year, and part-time faculty often find out from quarter to quarter whether they will have classes to teach.

Ng described the feeling of unknowns about job security faculty face on a quarterly-basis.

“I could be here for 60 years, for example, and have to wait every quarter to find out if I’m still here or not,” Ng said. “I’m not sure that’s the best way to thank someone for excellent service and teaching and then to say, ‘We have other priorities.’ And I’m not saying that’s what Fr. Sundborg or the Board [of Trustees] are saying, but that’s how people feel, and so I think we just need better and clearer communications.”

COST DRIVERS

Cuts are rampant, but what’s unclear to many is the factors driving the need to cut in the first place. In an email statement to the Spectator, Provost Dullea outlined several key factors contributing to the cuts.

According to the statement, financial aid is expected to rise by $5 million and compensation for faculty and staff will increase by $3 million in the next year. In addition, the School of Law has been in decline in recent years, which is also a national trend. During this time of economic downturn for law schools, Dullea said ours will “need assistance from the university to complete its transition.”

“I WOULD LIKE TO THINK THAT THEM HAVING TO CUT LEARNING COMMUNITIES IS REALLY NECESSARY FOR SOMETHING ELSE, BUT IT’S HARD WHEN YOU DON’T REALLY KNOW WHY.”

Doni Uyeno, Third Year International Studies Major

Many faculty surveyed said they believe Division I Athletics is a big cost driver, but administration has not confirmed or denied this assertion. According to Chief Financial Officer Connie Kanter, Athletics will endure the same cuts as the rest of the university. She said currently, 4.4 percent of university spending goes toward Division I Athletics.

“I think many of us in the faculty would want to know more about the cost-benefit of Division I sports and that’s a kind of sore-spot for many,” Washburn said, adding that he’s curious about things like whether or not a coach’s salary comes out of a professor’s salary.

It is still unclear how much revenue Athletics generates in comparison to its loss. Kanter was unable to give a clear answer during her transparency forum on Monday night, where she fielded questions from students and faculty for over an hour.

In an email to the Spectator, Dullea said, “Athletics does cost money, but it also brings in students who would otherwise not come here and it provides valuable ways for the university to connect to alumni and the broader community.”

It still remains unclear whether or not there is significant financial loss due to Division I Athletics and if Athletics spending hurts the academics of this institution.

In the fall, President Fr. Stephen Sundborg, S.J., announced that the university would seek court review of adjunct unionization.

The university has hired lawyers from Sebris Busto James, a firm that’s been “representing employers since 1992” according to their website.

Since beginning this legal battle, the administration has explicitly refused to disclose the cost of legal fees, saying that because it’s an ongoing fight, they have no need to disclose such information.

Provost Dullea said he is not comfortable discussing legal fees. However, when presented with the thought that budget cuts to Academic Affairs are a result of the legal battle, he said:

“I am comfortable saying that I do not share the perspective that unionization issues are driving the need to cut money in Academic Affairs.”

In addition to the aforementioned costs, the university is spending heavily on new building projects.

The provost said while the university is not in debt, it has purchased bonds to fund various building projects over the years. He said the most substantial project at the moment is the Center for Science and Innovation.

Dullea added that bonds take a long time to pay back and we still are, for example, paying the bonds for the renovations to the Lemieux Library, which was completed back in 2010.

“I wouldn’t say we’re in debt,” Dullea said. “Because that just sort of sounds like we owe more than we have. But the university has gone out for bonds to do construction projects and when you do that, you often times have lengthy, decades-long repayment plans and we’re working through those and that’s part of the annual budget. That’s one of the things we need to cover here.”

MOVING FORWARD

While the exact details of the budget are still unknown at this point, the changes may have negative impacts in the classroom and, effectively, on the students.

The president announced on Thursday that tuition will increase by 3.93 percent next year, following a 3.97 increase to this year’s tuition.

Rachel Larson, second year psychology major and academic mentor in the Justice in a Diverse Society Learning Community, said professors are a big part of the reason she’s still at Seattle U, and she hopes faculty will be treated with fairness.

“The professors are the ones that make this university,” Larson said. “They’re what keeps me coming back and it’s not okay to just cut them because we’re spending so much on other things. It’s a university; learning is what we do.”

Once the official budget is approved in May, more definite analyses can be made, but for now, many questions remain unanswered.

“I would like to think that them having to cut Learning Communities is really necessary for something else,” said Doni Uyeno, a third year international studies major and academic mentor for the Power and Narrative Learning Community. “But it’s hard when you don’t really know why.

Tess can be reached at

triski@su-spectator.com