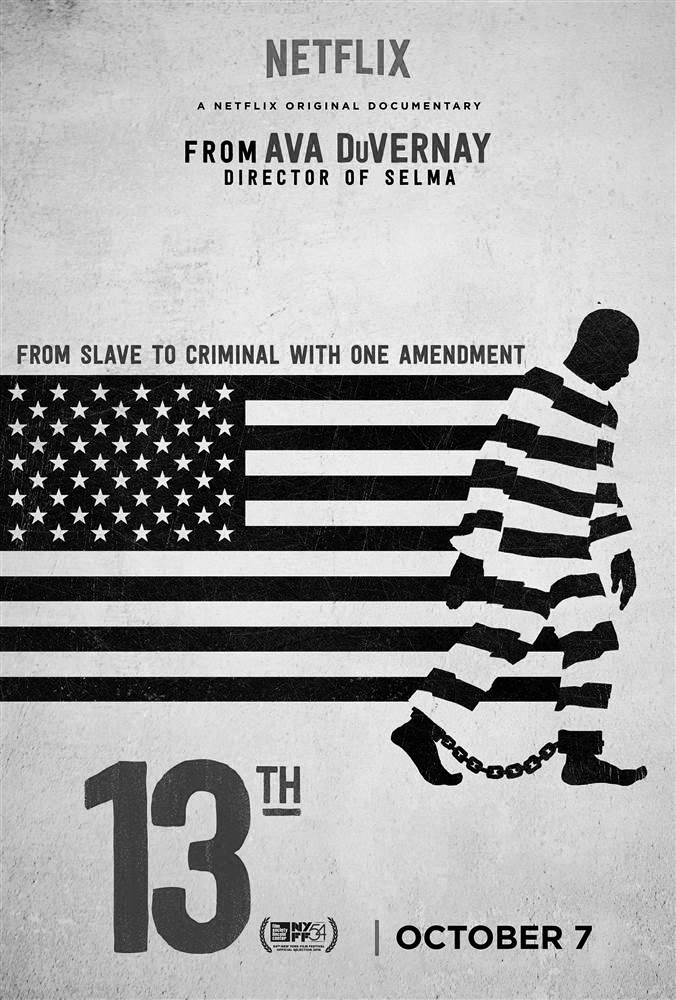

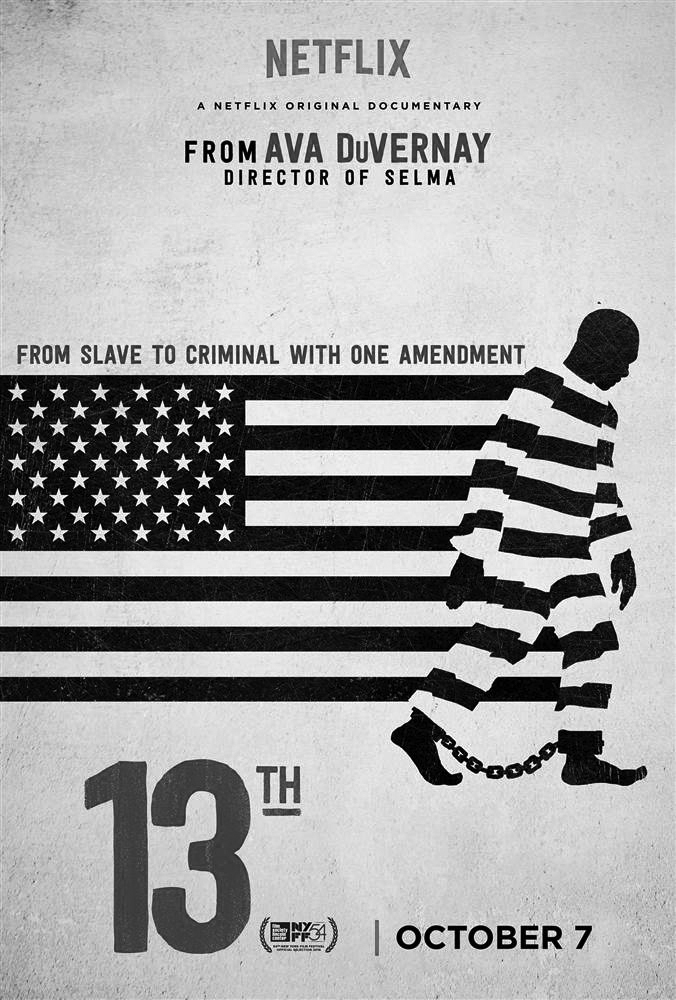

Since the shooting of Michael Brown in 2014, police brutality has become a common topic within the public sphere. Many regard police brutality as a surface-level issue but “13th,” a documentary directed by Ava DuVernay, analyzes this topic through a historical lens to address the problem at hand.

The film begins by describing the use of prison slave labor at the end of the Civil War. A clause in the Thirteenth Amendment accepted slave labor as punishment for criminals. This became a loophole that many upper-class white men took advantage of, arresting many black people for the purpose of using them for unpaid labor. The documentary follows the development of the criminal justice system over the course of United States history.

Professors, authors, activists and politicians describe the methods individuals such as Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton used to capitalize off of white fear and hatred of black Americans. These tactics were used in order to gain political power, as well as to boost the profits of businesses.

At roughly 90 minutes long, this film is packed with information and insight into the problems with the criminal justice system, as well as how those problems manifest themselves in the form of police brutality.

13th reveals a long history of corruption and conspiracy. In modern history, this began with Nixon’s use of “criminals” as a coded term for black people and Reagan’s fixation on crack rather than cocaine. But more recently, it includes George H.W. Bush’s use of “dog-whistling” in his ads, and Clinton’s laws convicting black people of petty crimes with lifetime sentences. Today, this corruption manifests itself in business investment in the prison system.

Particularly revealing was the segment on ALEC (the American Legislative Exchange Council) which has been running the United States government by directly connecting corporations with the legislative process. This council has written laws, on which both business representatives and legislators voted with equal say.

ALEC has influenced the criminal justice system by allowing companies such as the Corrections Corporation of America to form contracts with the U.S. government, binding them to keep prisons full of criminals. ALEC has also allowed companies like J.C. Penney and Microsoft to utilize prisons as manufacturers for their products.

With expositions like these, Duvernay provides hard evidence to the systematic oppression of black people that began with slavery, and lives on through the prison system.

When Richard Nixon called for the prioritization of “law and order,” and when he called for “total war against the evils that we see in our cities,” it is revealed as a coded way to appeal to southern Democrats who wanted to see the defeat of black protestors. Later, when Ronald Reagan refers to the “war on drugs,” the film argues that he refers to a desire to remove black people from the American public and place them in prisons.

Then in a particularly powerful sequence, Duvernay draws a parallel to the present, juxtaposing violent clips from the civil rights movement with voiceover and clips from Donald Trump’s rallies. In doing so, Duvernay argues that Trump is capitalizing on the same fear and hatred that Nixon, Reagan and Clinton capitalized on, using coded terms to appeal to the same racism that has existed since the creation of this country.

Since the protests in Ferguson in 2014, many have asked why police brutality has surged. This film though points out that police brutality is nothing new, and has only began to be documented. The interviewees in this film argue that this follows a trend of shock value leading to change. It happened in the antebellum South with autobiographies by slaves, in the 20th century with images of lynchings and news coverage of protests, and it’s happening now with videos of police officers shooting unarmed black men. This film expresses that the unveiling of police brutality is merely the surface of a deep history of systematic oppression rooted in the criminal justice system, which offers a fresh perspective that portrays a system in a way that makes it understandable for the general public.

This film is rated TV-MA, and contains clips of police shootings and racially motivated violence, as well as fictional scenes of rape. It’s available on Netflix for subscribers.

Josh may be reached at

jmerchant@su-spectator.com