“Iraq is Harvard for terrorists. If you want to be a terrorist, you go to Iraq,” said presidential candidate Donald Trump on Saturday, May 7 at a rally in Lynden, Wash.

Hate speech has fueled Trump’s campaign for the better part of the past year, as he’s used his speeches to target Muslims, Mexicans and other groups as enemies of the U.S. While many voters are shocked that he has made it this far into the presidential election, junior strategic communications major Areesa Somani believes his success is a reflection of the country’s current social climate.

“People look at him [Trump] and they say, ‘This is not who we are.’ This is everything that we are. And this is everything that our media climate and our power structure has led to—it’s led to this epidemic of hate manipulating our politics,” Somani said.

Somani recently conducted a 398-participant survey of primarily Seattle U students. Her area of research: hate speech.

While the lines around what constitutes hate speech are easily blurred, it is defined by the American Bar Association as “speech that offends, threatens, or insults groups, based on race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, or other traits.”

Somani became interested in the subject through her own experiences of being bullied and receiving hate speech as a Muslim-American growing up in a post-9/11 society.

When she experienced hate speech as a child, her family and Muslim community urged her not to confront it. Instead, they echoed the mantra: “Prove them wrong by achieving great things.” For them, fighting back was to get good grades, volunteer, and let people see you as a human being.

“It really wasn’t until five months ago that I realized that all of that, the whole ‘Prove them wrong by achieving great things,’ argument, is a lie,” Somani said “And that was when I encountered hate speech at SU.”

In Nov. of 2015, Somani responded to an anti-Muslim post on Yik Yak—a phone app that allows college students to anonymously post short texts for the rest of the campus community

to see.

“This person still couldn’t see that I was a human being. The thing is that this happened on Seattle U’s Yik Yak page, and nobody else stood up for me even though people had clearly seen this post,” Somani said.

Shortly after this incident, Somani conducted her research. She surveyed 398 people—primarily Seattle University students—to see how different people choose to confront hate speech.

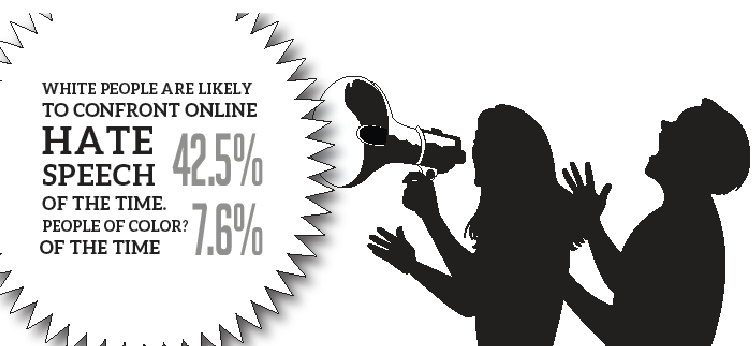

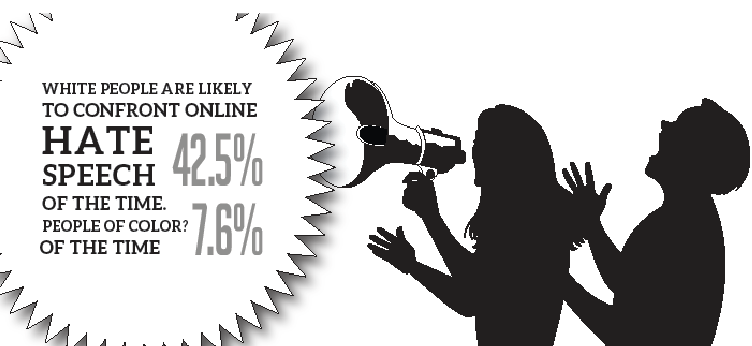

Somani discovered that on average, white people are likely to confront online hate speech 42.5 percent of the time. People of Color? 7.6 percent of the time, on average.

She attributes this significant gap to the physical and psychological risks People of Color face when confronting hate speech.

“Freedom of expression is not free,” Somani said. “When we’re talking about why People of Color speak out against about hate speech and why they can’t feel free to express themselves, it’s a question of physical safety, and it’s a question of taking a risk that won’t see a beneficial outcome.”

As a result of the tremendous risks, white narratives are the ones primarily being told through mass media—further silencing People of Color. Somani said there are endless stories of hate crimes against People of Color that are not told through mainstream mass media.

“There were two Muslim boys in Indiana two months ago that were shot execution-style,” she said. “And we don’t hear about those things either.”

Somani said she believes the Seattle U community has a responsibility to incorporate the issue of hate speech into the university’s social justice agenda.

“That’s been really disappointing to see at SU, is that there’s this huge focus on social justice, but it’s clear whose opportunities and whose voices are being expressed and whose are not,” Somani said. “If you have a media climate that favors white discourse, you’ll have a society that favors white discourse.”

For Somani, the heavy burden of hate speech is something she carries with her every day.

“Because I’m a Muslim-American and I’m a racial minority, I feel like every day I’m fighting,” Somani said. “You’re not only fighting for your right to exist, you’re not only fighting for your right to life—you’re fighting for your dignity, and you’re fighting to be heard, you’re fighting to be yourself, and you’re also fighting the system at the same time. And sometimes it’s too much.”

————–

About two weeks ago, Associate Dean of the College of Education Bob Hughes was at a Capitol Hill Starbucks with a colleague from Seattle Central College. As they were seated, drinking coffee and conversing, a young white male approached them, spat at them and repeated, “fucking nigger bitch.”

“He directed his anger at my colleague, having never met either of us. He saw two African Americans sitting in a Starbucks and decided that it was okay to assault us,” Hughes wrote in a blog titled, “Are we in a post-racial world? In a word, NO! Make that, Hell No!”

Hughes said that the explicit act of hate speech, accompanied by an assault, is indicative of the looming presence of racism perpetuated by those in positions of privilege.

“What’s interesting is that young man doesn’t see my privilege. All he sees is my race. And that’s what that says about us as a society,” Hughes said. “Race still matters and race is privileged in this society, and here’s a young man who acts on that personal sense of it.”

Hughes said that if he could change something about people’s perspectives on racism, it would be the idea that we have moved beyond it.

“Stop pretending it doesn’t exist. Stop pretending that we’re post-racial,” Hughes said. “Let’s start honestly confronting our own racial biases and our racial perspectives. Let’s start honestly having that conversation and let’s stop pretending. That’s what we have to do.”

————–

Humanities for leadership major Joseph Delos Reyes is a Filipino-American and member of the LGBTQ community. He attended Catholic school his entire life and often experienced hate speech due to his sexuality.

In one particular instance, Delos Reyes’ peer forcibly shoved him and called him a “faggot.” Delos Reyes reported the incident to the principal.

“And [the principal] said, ‘I’m so sorry. That should never happen. I will talk to that student. But in the future, next time don’t flaunt it,’” Delos Reyes said.

Delos Reyes said that this implicit form of hate speech teaches the recipient that their way of being is inherently wrong.

“I mean, that’s not a typical hate speech sort of thing, but it plants the seed in your head, and that’s what hate speech does. It’s like, ‘Your identity is so obvious and so wrong that I can point it out and that you shouldn’t flaunt it,’” Delos Reyes said.

Delos Reyes described a time in middle school when the priest was giving a homily on euphemisms. The priest said that in reference to gay marriage, the word “marriage” is used as a euphemism for “destroying the sanctity of marriage and turning your back away from God’s love.” For Delos Reyes, the ideologies perpetuated by people in positions of leadership bred a sense of self-hatred and denial.

“To be a sixth grader trying to find acceptance and to hear that being remotely gay is turning away from God’s love… then I have to adopt all of this language, too. I have to call other people a faggot because I can’t let other people know that I’m a faggot,” Delos Reyes said.

He said that a misconception at Seattle U is that hate speech has to be explicit—a particular word or phrase. He wishes students knew that hate speech resides below the surface.

“It’s found in phrases and movements and laws and policies that have so much underlying hate speech to them,” Delos Reyes said.

Due to a fear of hate speech and physical altercations, Delos Reyes is perpetually aware of his mannerisms.

“So constantly something that goes through my head is, ‘Am I walking too gay? Am I too loud? Should I deepen my voice in this interaction?’ And it’s me trying to preemptively stop any hate speech or physical confrontation from happening,” Delos Reyes said.

Delos Reyes also spoke of the self-hatred perpetuated by standards of beauty in the Filipino community.

“So we [Filipinos] try everything in our power to be lighter skinned. Skin-bleaching products, even mixing our races, everything like that. It’s so unfortunate. And I’ve noticed myself being a victim of this sort of self-hating Asian paradox,” Delos

Reyes said.

————–

The three voices of Somani, Hughes and Delos Reyes capture a minute sample of the vast experiences of hate speech experienced by individuals on a daily basis due to race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, sexual identity and disability.

According to Somani, 75 universities in the U.S. have implemented a hate speech code. Seattle U has not. Somani said that considering Seattle U’s Jesuit values, it doesn’t make sense for the school not to condemn hate speech.

“Clearly something has to be done, but it’s up to us to figure out what that is,” Somani said.

Somani will present her research at the Seattle University Undergraduate Research Association on Friday, May 13 in Student Center 130B. All students, faculty and staff are welcome to attend.

Tess may be reached at

triski@su-spectator.com