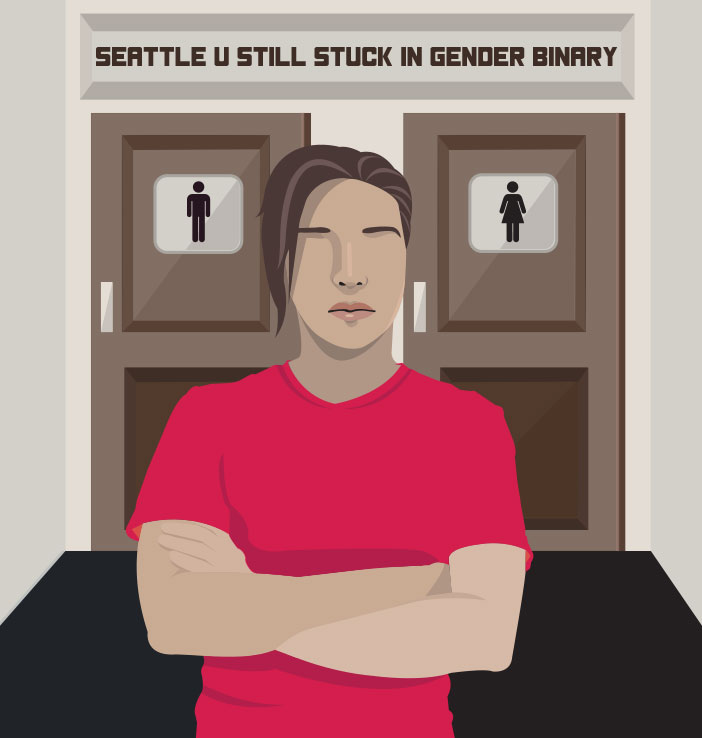

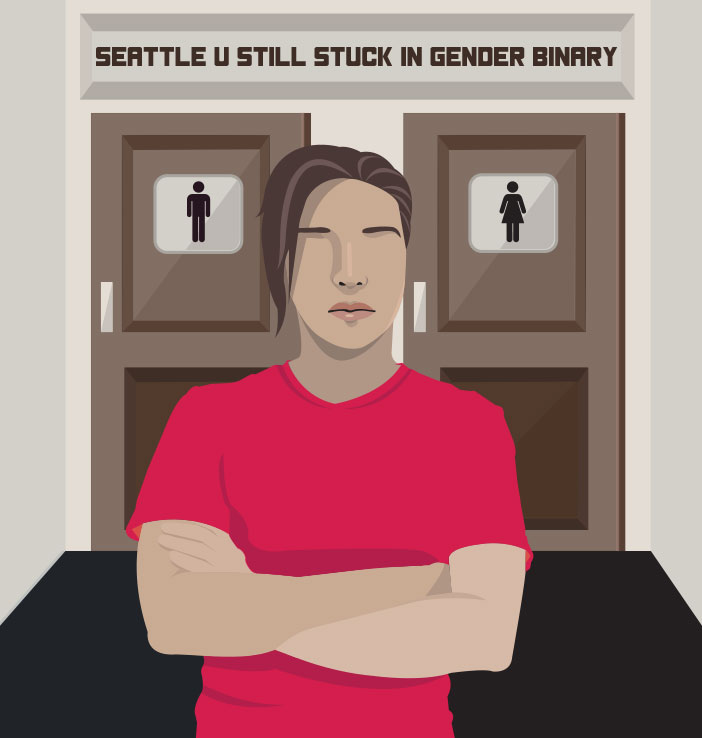

Seattle University has long struggled with making its campus inclusive for transgender, genderqueer or other non-binary students and community members. In 2010, students, faculty and staff developed a list of issues regarding inclusivity that needed to be addressed. This list included bathroom accessibility, training and awareness surrounding pronoun usage, and access to health care. For non-binary students, there are critical changes that still need to be made.

“I have to live with that issue, live with my identity, and I have to think about it critically,” said Juanita Rosales, a sophomore that identifies as androgynous, neither male nor female. “Identity is more complicated than it seems to be. People want it to be black and white, and they want people to be sure of themselves, but people don’t work that way.”

Seattle U is a binary school. This can be seen not just with the restrooms but also in dorm rooms, classrooms and in campus workplaces. Even in online forms, the different ways to identify gender are limited to just a few check boxes. Students like Rosales are forced to navigate this maze of gender discrimination with a heavy heart.

“I’m non-binary, and trying to explain that to someone isn’t the easiest, or to get people to understand that I’m neither, and I don’t feel any pull to either, is really hard,” they said. “People brush it off as ‘I’m confused,’ but I’m very sure who I am.”

The human body comes in a limited number of forms. Gender, on the other hand, is much more expansive. People have traditionally been limited to two sets of pronouns. Girls and women typically use she/her pronouns. Boys and men use he/his/him. This confined people to a dichotomy of lifestyles. The line of separation was drawn long before we were born, creating a strict mental division between two completely different sets of ideals. As we get older, these ideologies pervade our very way of thinking.

“A lot of people have trouble seeing gender as fluid,” said Maya Lall, a senior who identifies as queer or non-binary. “If you blur the line, it confuses people.”

Rosales and Lall have had to explain themselves on many occasions. The greatest difficulty, they said, is trying to make people understand why they don’t use gendered pronouns, why they don’t gravitate strictly to masculine or feminine characteristics, and, above all, why they fight for a gender-inclusive society.

To avoid issues in the classroom, Lall sends emails to their professors even before the quarter begins, explaining their pronouns and providing examples for clarity. In most cases, the professor is more than happy to comply, but it’s not uncommon for them to forget or create a situation where students are separated by gender. In these moments, it’s hard for Lall to know what to do.

There are people who condemn transgender, genderqueer and otherwise non-binary students, Rosales said. The same people are under the impression that gender neutrality is nothing but a counterculture fad that will fade just like any other popular trend. In this case, people fail to understand students at Seattle U who don’t belong to one gender alone, and this leads to many issues.

“It would really help if discussions about gender on campus went beyond asking people for their pronouns,” said Jamie Wipf, a senior who uses many different terms to describe herself, like female, tomboy, or gay. “[People] ask for pronouns, but I think a lot of people are still uncomfortable with non-binary genders, or don’t have as much of an understanding of it. Then, of course, you also get the folks who aren’t even at the level of asking for pronouns, or just haven’t yet gotten the chance to learn what that means.”

Similar to Wipf’s sentiments, Rosales thinks there are several opportunities for binary people to educate themselves. At the beginning of each school year, all Seattle U students are required to take an interactive survey called “Think About It”, which teaches them about the dangers of alcohol and sexual assault. This survey, Rosales said, should include more information about gender sensitivity.

“You can start in simple ways. Don’t assume genders. Ask for pronouns,” Lall said. “People who show you awareness make you feel welcomed in a space.”

There are many ways in which administration and faculty have made collaborative efforts to create an inclusive environment, one of which is the Committee for Improving Trans Inclusion. Born from a recommendation made by the original Diversity Taskforce back in 2008, the CITI was created to explore how Seattle U can be more welcoming to transgender and

genderqueer students.

The Campus Climate Survey taken last year showed that 76 percent of women and 78 percent of men were comfortable with the overall climate of Seattle U’s campus. Only 43 percent of transgender, genderqueer and other non-binary respondents related that same comfort.

“We need to provide for the needs of all our students, and to continuously be mindful of the evolving needs of students, especially those who might be bothered in our society or campus,” said Gabriella Gutierrez y Muhs, Co-Chair of the survey.

According to CITI member Jodi O’Brien, the committee began by creating a table of recommendations where each course of action is designated by its cost and political impact. And so projects like increasing the number of gender neutral restrooms on campus, or making it possible for students to easily change their name and gender in the registrar, made their way to the top of the committee’s priorities.

“You’ll often have people, often students, saying nothing’s getting done, this isn’t moving forward, the university isn’t doing anything, where as other people think they’re working very hard and giving a lot of their time doing this,” O’Brien said. “I think the biggest gap on our campus is that there’s not enough conversation between those groups.”

Other more costly projects were met with resistance from the Seattle U community. The committee wants to designate funding for Counseling and Psychological Services, she added, but also to hire a full-time professional staff member to focus on queer and transgender student services. Also on the to-do-list: health care plans for students and faculty to cover transgender related processes like hormone therapy.

In their class, the first ever seminar in transgender studies, O’Brien has introduced students to the idea of “permissible prejudice,” wherein institutions are judged by the actions and intentions of its most powerful administrators and not each and every member.

“You might have individual faculty or individual members of the board of trustees or individual university administrators who are opposed to this, but if the university has officially appointed a committee or taskforce and it’s occupied by people who have decision making authority, then that’s a good thing,” O’Brien said.

The CITI is full of faculty and administrators armed with the authority and power to enact immediate change. With the intent to provide gender nonconforming students, faculty and staff with universal access to the campus and its opportunities, the committee examined the university’s current policies, documents, procedures and structures.

Lara Branigan, Director of Design and Construction at Facilities Services, contributed as a CITI member by leading the effort to make non-gendered restrooms available throughout campus. With this project, additional signage was added to single user bathrooms, using a green star in a circle to signify that it was safe to use for transgender, genderqueer and non-binary students and faculty.

“We need options for anyone,” Branigan said. “My end goal is that everybody has a safe and comfortable time being on this campus, and remembers it as someplace they were included.”

Nick can be reached at nturner@su-spectator.com