Low income students at Seattle University struggle with balancing the value of an education with debt, insufficient scholarships and the nuances of wage and hours.

A college education is one of the best investments you can make—it is also one of the most expensive.

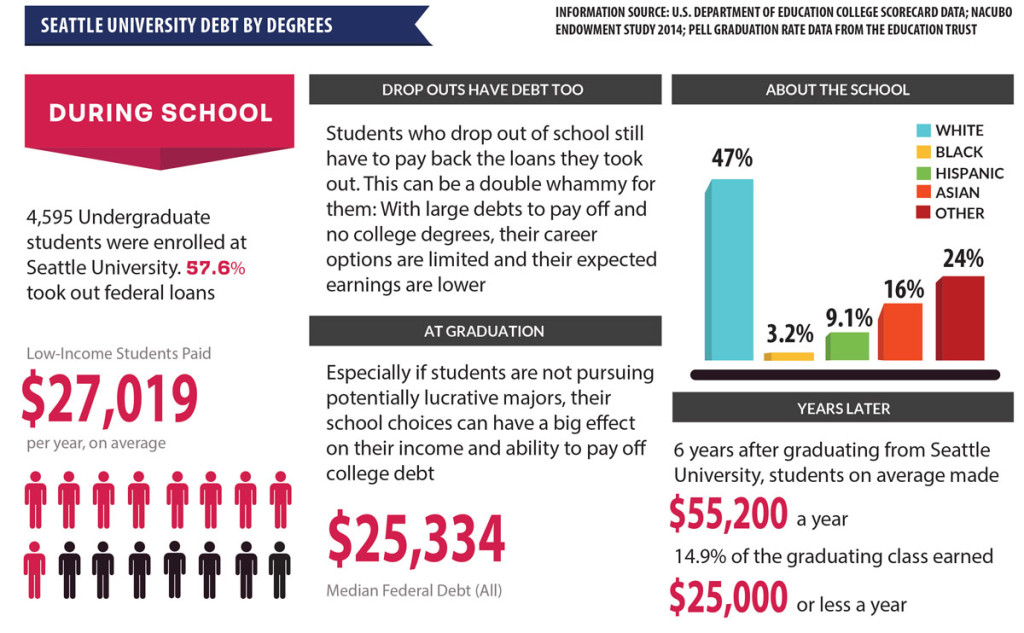

Last year, Propublica created an online database called “Debt by Degrees” which allowed users to examine federal data on more than 7,000 schools in the U.S. and see how well schools support their poorest students. They did this by comparing the number of students who had been awarded the Pell Grant: a federal financial aid package commonly given to those from households with an annual income less than $30,000. Many schools are extremely supportive of these students and many others are not.

According to the same database, in 2013 approximately 4,595 undergraduate students were enrolled at Seattle U, 57.6 percent of which took out federal loans. In the same year, the graduating class had a median federal debt of $25,334. On average this debt was paid over a 10-year amortization plan with monthly payments of $281.26. 6 years after graduating from Seattle U, students on average made $55,200 a year. 14.9 percent of the graduating class earned $25,000 or less a year. The average annual cost of attending Seattle U—including books, tuition, and living expenses—was $50,610. Only 23 of 344 comparable universities were found to cost more.

Despite these statistics, the graduation rates of Pell Grant students and the rest of the students were only slightly different.

Seattle U is a private, not-for-profit, four-year Jesuit Catholic University. At our school, and others like it, financial support comes in different forms: federal aid, state aid, institutional dollars and what is often lumped together as “private sources.” The Pell Grant—along with the Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant, the federal work study program and student loans—falls under the umbrella of federal aid. State funds are only for locals, which is why tuition costs less at Seattle U for Washington residents. For all need-based financial aid, the amount of money awarded depends on the information given by the student in their Free Application for Federal Student Aid, more commonly known as a FAFSA form.

According to Jeff Scofield, Director of Student Financial Services, the FAFSA form is meant to treat everybody the same. In doing so, he adds, it fails to consider several important factors.

The FAFSA doesn’t take into account differences in cost of living. Somebody who used to live in Alaska, for example, will receive the same amount of aid through their FAFSA even after they move to San Francisco where the cost of living is much higher.

“You get treated the same even though your income doesn’t go as far in one place or the other,” Scofield said.

The information in a FAFSA form only examines a snapshot in time. In other words, your aid eligibility for the following year is determined by the prior. For families in a stable financial situation, this snapshot is accurate. For other families, this is a problem. Many things can happen that affect their income: a parent was laid off from work or was in a car accident and all these extra medical expenses have to be paid for, and so on.

“[The FAFSA] doesn’t capture those kinds of events,” Scofield said. “It doesn’t get at those nuances or events that many families have to deal with.”

Sophomore Marthadina Russell was awarded the Pell Grant when she applied to Seattle U. It wasn’t until she came to college that she fully understood her family’s financial situation. She had been living on her grandmother’s property with her parents, but following her grandmother’s passing in 2014, Russell had to support herself.

“That was the one time where my grandmother wasn’t able to help,” Russell said. “That’s when I really realized how little money my family had. I had to do all of the work.”

Though Russell was born in Portland, her parents live in the Philippines where her mother has two jobs, one as a cleaning lady and the other as a caretaker at a retirement home. Her father was a construction worker until his disabilities led to his retirement. He has lived with many health issues: lung cancer, diabetes, hip and heart problems. He also had a triple bypass, a very serious open heart surgery procedure that is done when the blood vessels that feed the heart are too clogged to function properly.

Russell applied for loans to attend college but every bank rejected her based on the grounds that her parents were unlikely to pay them back. She received less federal aid from Seattle U than any other school she applied to. Help came from no one, so she got a job working four to eight hours a week at the Arrupe House. She sends part of her paycheck home to her parents.

“Honestly, having all of this financial stress has made me push so hard just to stay here,” Russell said. “I love that I’m going to college and it would terrify me if I weren’t getting an education, and so I fight for it. My claws are out. I’m fighting for my life to stay here and get my education. I think it’s made me pretty strong, pretty kick butt.”

Starting April 1 of last year, Seattle U raised its minimum wage of student employees—such as Russell—to $11 an hour, with a further increase to $13 an hour this January. For some of them it was a welcome gift; for others, not so much. Some students from the former group were paid more but they also received a new schedule with less hours. This meant they were virtually making the same amount of money, despite the raise.

For junior Juliana Bojorquez, less hours meant more time to do other things like intern or focus on classes. She has been working as an office assistant in the college of nursing since freshman year. Before the raise, Bojorquez was working around 15 hours a week. Now she’s working roughly 10 hours, but her paycheck hasn’t changed significantly.

“I understand that with the raise, it means that other things have to get cut,” she said.

The size of our school is a commonly overemphasized detail when it comes to endowment. While some believe that with less than five thousand undergraduate students, Seattle U should be able to better support its students financially, the school’s endowment is in the millions of dollars, not billions. Seattle U’s ability to fully fund every department is finite, which is why efforts to enhance student life don’t always go as planned.

Junior Christine Rominski found herself in a similar situation when she also got a raise at the beginning of the quarter. Like Bojorquez, her hours were reduced and she was paid roughly the same as before, but the consequences were greater. As a peer advisor in the Matteo Ricci College, Rominksi meets with her 8 advisees individually and in groups to discuss class registrations. She’s afraid that, because of her new schedule, she won’t be able to provide them with the help they need to take the required classes they need and graduate on time.

“This issue has very little to do with the breakdown of numbers and what is written on my paycheck,” Rominski said. “The issue here lies in the quality of work. This school isn’t cheap and time is precious.”

As Rominski says, Seattle U is one of the most expensive schools in the country. Students here enjoy luxuries that are otherwise nonexistent at less expensive schools. Sophomore Sharon Tang argues that those luxuries are unnecessary. She believes that great professors can be found at all schools, no matter how big the endowment or how high the tuition.

“A school like SU is top tier in terms of amenities and exceeds what people are naturally entitled to,” Tang said. “An education is a must, but small class sizes, a beautiful gym, and state of the art technology are all extras that a student can go without.”

Those amenities can lead to a lot of debt later in life. But Thaddeus Teo, a former Seattle U graduate student currently involved with the Alumni Relations believes a college education is worth every penny. Still, dealing with student loans after graduation can be a serious disadvantage.

“It’s part of the American dream, where people want to own their homes or want to grow up and maybe get married and start a family and settle down,” Teo said. “That money that goes towards my student loans could be going towards that.”

Sophomore Veronika Zwicke is bound to find herself in a similar situation after she graduates. She’s currently working two on-campus jobs to support herself and pay

for tuition.

“I was just basically spoon-fed this great stuff about SU, how they’re going to make sure everything is paid for,” Zwicke said. “I’m not going to be able to start the life I want to right away. It’s going to be living way below my means just to pay off that student loan.”

The Office of Student Development offers support to students with financial problems. According to Vice President for Student Development Michele Murray, the school has an emergency fund set aside for when a student can’t afford food, has fallen ill or needs shelter.

“It’s very personal what the needs are, and then what the remedy is for the individual student. It’s less of a blanket policy,” Murray said. “One of our hallmarks as [a] Jesuit institution is that we care for the individual student.”

Though the needs of the individual are important, the issues Russell and Zwicke face can be attributed to a wider, institutional dilemma. The price of higher education has been rising for decades. High school graduates who intend to pursue a professional career are expected to go to college. At least, that’s what they’re told, and so college–along with financial insecurity related to college—has become the new standard.

Wide recognition of this standard is made evident by efforts of Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), who wants to hear from the more than 40 million Americans paying off their student debt, and President Barack Obama, who is pushing for free community college. Murray launched a comment form on her website in late January, encouraging people to share their struggles to afford college, to pressure Republicans to address college affordability. In his last State of the Union Address, Obama said he would continue to work on giving every college student two years of free community college.

While student debt is on the minds of Seattle U students and congress alike, it is unclear whether any headway will be made on the issue, or if the struggle to balance education with financial security will remain the unpleasant standard for the foreseeable future.

Nick may be reached at nturner@su-spectator.com