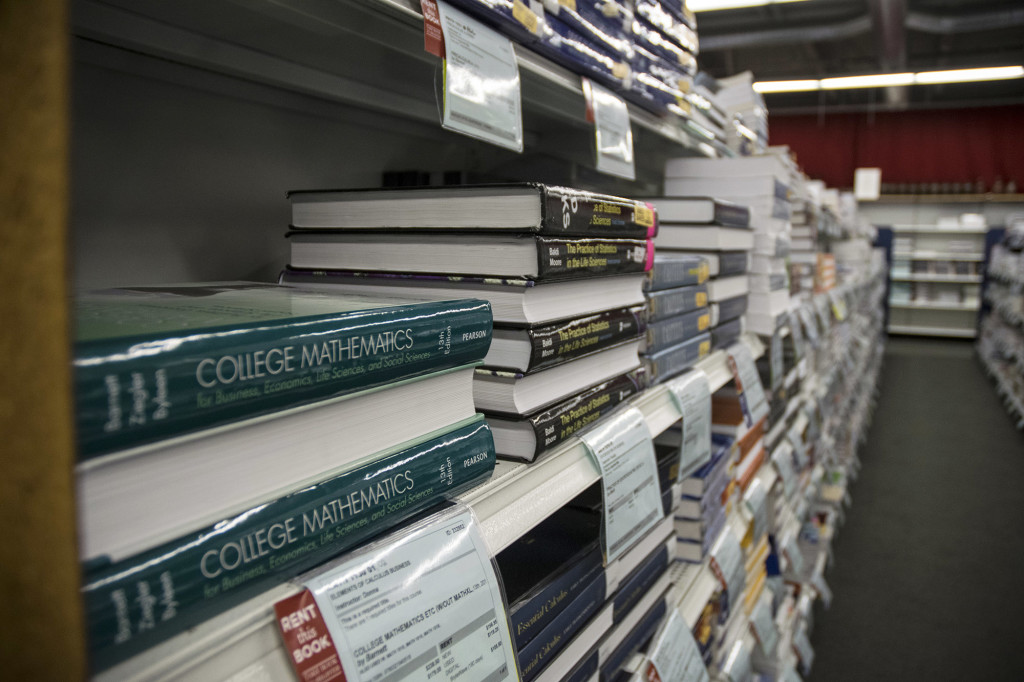

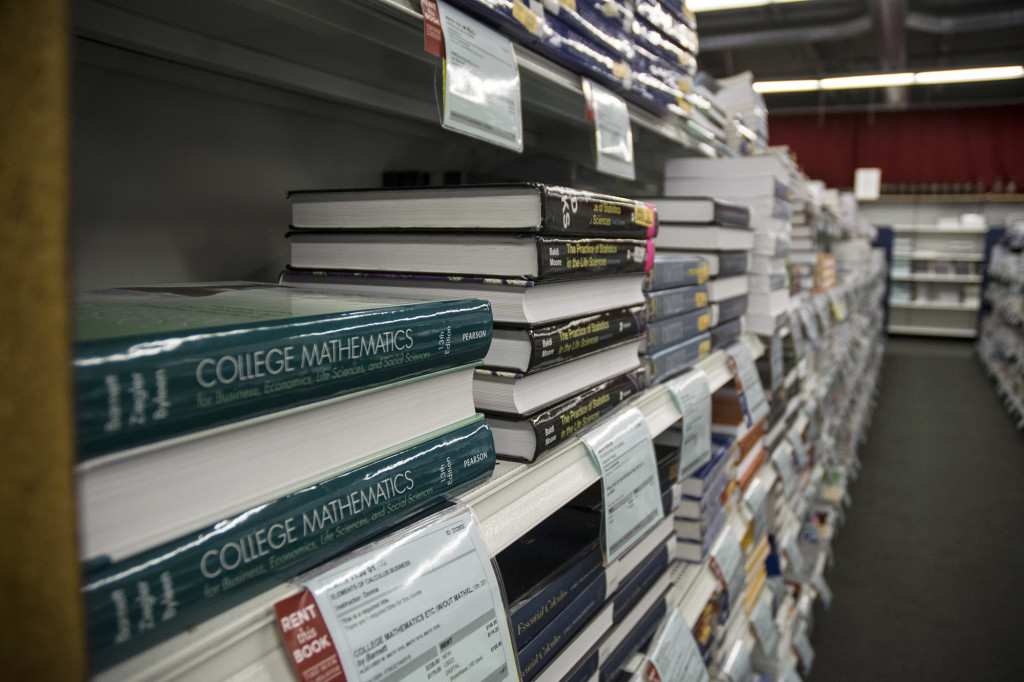

The idea of having to pay less—or nothing at all—for textbooks is one that would excite just about any college student, especially those with textbook-heavy majors. A new bill, titled the Affordable College Textbook Act, was introduced in the United States Senate on Oct. 8 in hopes of combating the increasing prices of textbooks and to provide some financial relief to students who already pay exorbitant amounts for school.

Megan Rahrig, a junior political science major at Seattle University, thinks that the Affordable Textbook Act is a good idea.

“Not only does it reduce cost, but it prevents the printing of tons of copies of books that become outdated after only a year,” Rahrig said.

Though the bill was originally introduced to Congress in 2013, it never advanced. Senators Dick Durbin (D-IL), Angus King (I-ME) and Al Franken (D-MN) reintroduced the act in another attempt to cut back on the skyrocketing book prices. One of the primary backers behind the legislation is The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC). On their website the organization explains that, “the U.S. college textbook market remains dominated by traditional publishing firms that make it difficult for open-textbooks to gain visibility.”

These open-textbooks, or “open educational resources,” are, as described by the site, “free, online academic materials that are released under a license permitting everyone to use, adapt, and share the content.” They are not only free online, but sold at a significantly lower cost in print compared to other textbooks. It also allows for a more beneficial involvement with digital technologies—and a bigger relief on your back. Students can also access open-textbooks on phones, tablets and laptops.

The days of having to pay excessive amounts for new version of a textbook—compared to a slightly older one that costs significantly less—could soon be over.

“They’re giving grants to universities to create their own textbooks, instead of making already-established book companies charge less for books,” Rahrig said.

According to The College Board, at a four-year public college, textbooks cost students an average of $1,200 per year. This is on top of housing, meal plans and other fees that students must pay in order to attend college. The rise in price has been a consistent 6 percent increase per year since 2002, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO). While textbook costs rise, so does the cost for tuition. The College Board website presents figures that demonstrate the 146 percent increase in college tuition for private four-year institutions, from about $12,000 to $32,000, and a 225 percent increase from $2,800 to $9,000 at public four-year institutions.

According to the United States Public Interest Research Group, 65 percent of students surveyed said that they “had decided against buying a textbook because it was too expensive.”

Open textbooks have been available since 2012 after OpenStax College, a free, peer-reviewed open-textbook initiative was created. Originally funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, it offers 25 textbooks covering basic subjects like Chemistry, Pre-Calculus, Psychology, and U.S. History. More textbooks are to come, and each book is subject to changes based on users needs. Unfortunately, most of the schools that have already adopted OpenStax as an alternative to purchasing textbooks are public universities, which means Seattle U has not yet adopted it.

Freshman Bailee Clark said she is also in favor of the act.

“If you can get [the textbooks] for free, and it will get rid of the necessity for paper textbooks and lugging them around, I’m all for it,” Clark said. “I think it would also help to get rid of paper waste. The only downside I could see is if my computer crashed, but I could always use the school computers.”

Students aren’t the only ones excited about the prospect of cheaper textbooks. Philosophy professor Jason Wirth said he feels that the whole textbook market is a predatory scam.

“The predatory aspects of producing a textbook—extraordinary costs, ‘updated’ editions—they aren’t in the interest of anyone going to these schools,” Wirth said.

The bill, if passed, will not only save students in America an estimated total of $1 billion, according to the U.S. Public Interest Research Group; it will also allow more students to save on textbooks to put towards tuition itself.

“It’s a good thing that we’re going to have a serious discussion about resolving [this issue],” Wirth said.

Scott may be reached at sjohnson@su-spectator.com