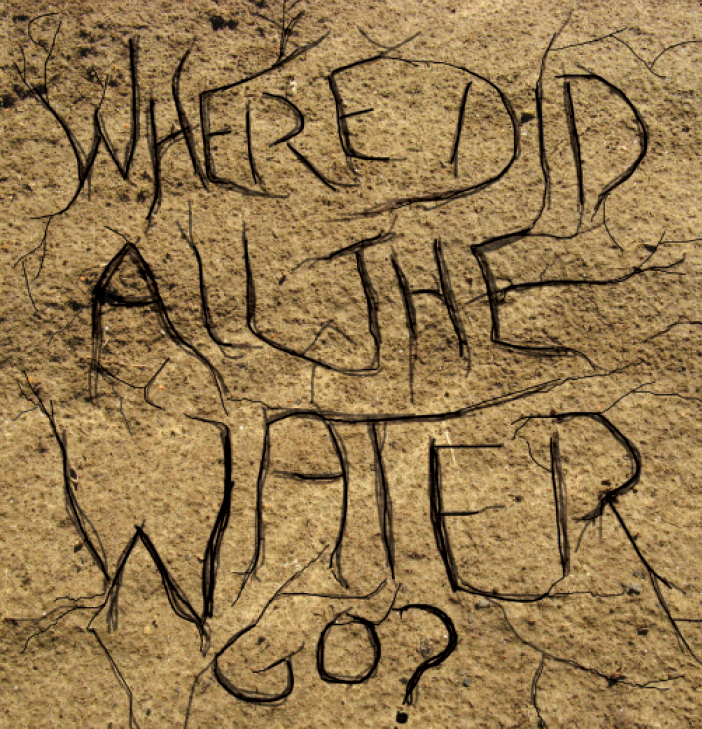

Driving through Snoqualmie Pass this past winter felt post-apocalyptic. The hills were bare and brown with the exception of some patches of white snow. Chair lifts were not moving. Snoqualmie Pass had closed down early this year due to lack of snowfall.

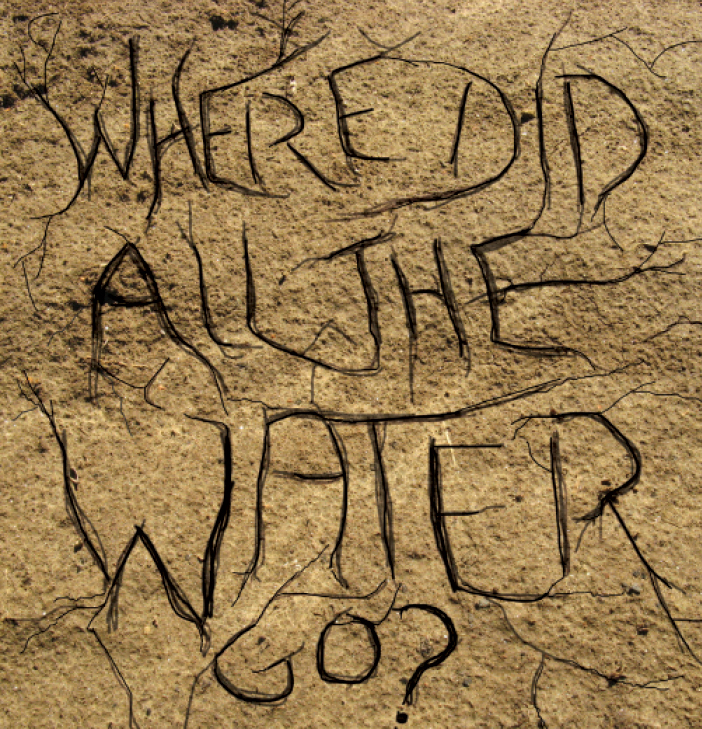

Rattlesnake Lake in North Bend has been at concerningly low levels for this time of year. Stumps that the water usually covers by this time are barely submerged. Next to Rattlesnake Lake is Cedar River Watershed. According to the Washington state Department of Ecology, the Cedar River Watershed is one of the 48 of 62 watersheds in Washington that have 75 percent or below of their normal water. It also helps provide the city of Seattle with drinking water.

One thing remains very clear—the drought declaration by Governor Jay Inslee on May 15 calls for Washington to take notice.

It can be argued whether the Washington drought is linked to California. Similar to what Oregon and California have been experiencing, Washington has a lack of snow cap in the mountains, significantly impacting the amount of water supply available.

Although Washington is not planning on implementing mandatory rationing of water, as California recently did, the conservation of water is still extremely encouraged.

“I think we need to be conscious of how much water we really use,” said sophomore environmental studies major Mike Tommins. “We really need to work, not just at an individual level but at a larger systemic level, in order to bring awareness to how much water we waste.”

Statewide, the Department of Agriculture has reviewed the possible economic consequences of the drought and, according to Jeff Marti, an environmental planner and drought coordinator at the Washington Department of Ecology, a loss of about $1.2 billion are expected.

The kinds of crops most vulnerable in these times of drought are crops that cannot go without water for a couple of weeks like perennial plants, which include apples, cherries and grapes.

“These areas of agriculture impacts are especially acute in certain basins where there is a high intensity of irrigated agriculture,” Marti said. “I would say the Yakima Basin is currently in the greatest amount of stress in terms of water supply.”

Because snow melt has been so dismal this year, the Yakima Basin will not have enough water supplies to meet all the needs of all the farmers. Farmers with junior water rights will have their rights reduced or curtailed entirely. According to Marti, a majority of those irrigators grow perennial crops.

The Department of Ecology is working with these junior users to allow them to use emergency wells where they can use ground water instead of surface water. Senior water users will primarily make use of pumping surface water, but the department needs to make sure that utilizing ground water for junior users does not violate senior water rights. In other words, whether pumping surface water or ground water, senior users will receive priority access to water in comparison to junior users. Those competing for access to water, whether for recreational use, agricultural use, industrial use, or otherwise, will be given senior rights based on whether their use is most beneficial of the water available, as determined by Washington State Law. Rights also vary depending on the type of land involved.

“We’ll be looking to acquire water rights to offset the impacts of that ground water pumping,” Marti said.

The Walla Walla Basin also appears to be in a dire state right now. Fish rescue operations have already been engaged to combat the harsh effects of the drought.

In certain creeks, water flow is so low that adult fish cannot move upstream and juveniles end up trapped and stranded in water pools that are no longer connected to each other. These fish have been captured and moved to spring where there’s more water.

The Department of Ecology has also worked with irrigators to provide pulse flows of additional water down the river, helping adult salmon move upstream.

“As we get farther into the summer, we expect other areas to start feeling that pain as well,” Marti said.

The seasonal outlook from the national weather service within the next several months estimate continued higher than normal temperatures. As we get into the beginning part of summer, the forecast also predicts lower than normal precipitation.

Demand for water is expected to continually increase just as the water supply decreases, making the situation even more challenging.

The last state-wide drought declaration occurred in 2005, and, in comparison, our current snow pack conditions are considerably worse.

“This year we’re looking at record low snow pack conditions for most of the state,” Marti said.

Several criteria are involved in determining whether an area should be declared for drought, one of which being whether the area will receive less than 75 percent of normal water supply.

In Washington, the Water Supply Availability Committee has water supply, forecast, and climate expertise, and they have evaluated snow pack conditions and river forecast information periodically through out the year.

“This spring we started identifying water sheds that were going to be below [those] 75 percent criteria,” Marti said. “Once you identify those water sheds, then you also have to determine whether or not you expect undue hardship to occur there as a result of water shortage.”

The Department of Ecology, along with the Water Supply Availability Committee, the Executive Water Emergency Committee, and written approval from the governor can thus issue an order to declare an area for drought.

Weather researchers also predict that the drought emergency is likely to become a worse problem because of a strengthening El Niño tropical weather pattern in the Pacific Ocean.

Thanks to El Niño, dry and warm conditions are on the horizon, and not just through the summer, but well into the coming fall and winter seasons. This, on top of the low snowfall still projected, combine to raise many concerns for farmers and wildfires increase the possibility of wildfires.

Apart from the general farming comm unity, residential neighborhoods, state-wide industries and local craft brewers are expected to be affected.

According to the USDA, Washington puts forth 79 percent of hop production in the United States. After this drought declaration, water restrictions on hop production will take its toll, especially since up to three gallons per day is used per plant.

The community is working to lessen restrictions for water enough to profit through the September harvest. The demand for hops and the expensive price for acreage coupled with the shortage of water makes it difficult to determine what should be given the most attention.

“I find that a lot of the general community away from SU isn’t as passionate about environmental issues,” said freshman environmental studies major Stephen Thorne, “which is unfortunate because we’re in the middle of a huge one right now.”

As for our campus, there are several resources that Seattle U community can access to help in the effort to be more sustainable and combat this drought crisis. The Center for Environmental Justice and Sustainability, as well as our facilities department on campus, can help bring awareness to our need for water.

Other resources include the learning community Earth and Society of Campion floors two and three and the Environmental Studies department in the College of Arts and Sciences.

“We almost have to act as if we’re in an extreme situation so that we save as much water as we can rather than undervaluing water and really wasting it beyond our necessary consumption levels,” Tommins said.

Vikki may be reached at vavancena@su-spectator.com

Siri may be reached at ssmith@su-spectator.com