The surge of nationwide demonstrations over the past few months has made evident the many ways that citizens and students assert their rights to protest.

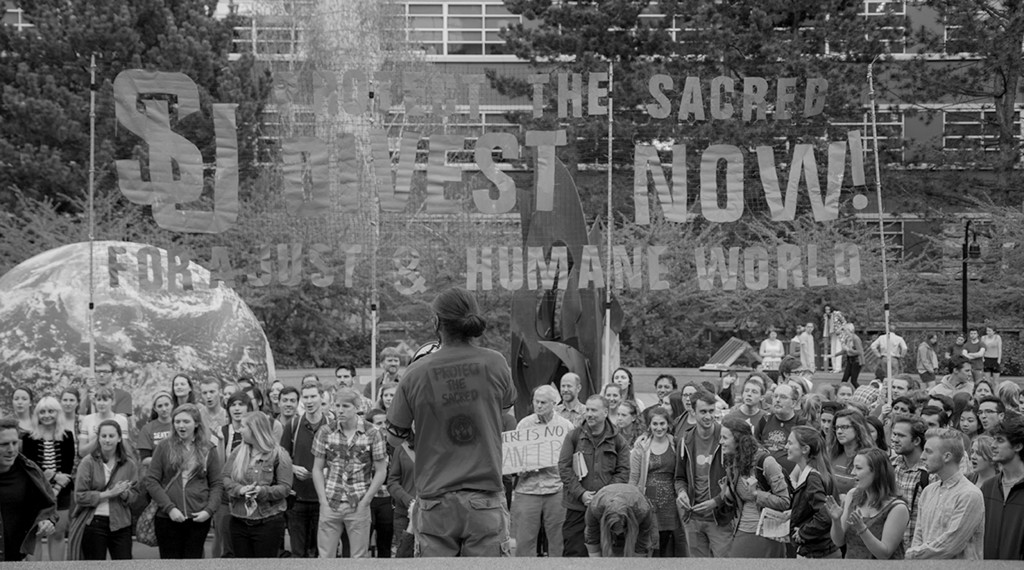

Seattle University’s Sustainable Student Action is hosting a Non-Violent Direct Action Training on Feb. 7 to educate students about demonstration tactics. In the past, SSA has led protests on campus regarding their campaign for divestment against fossil fuels. Other recent on-campus protests include those addressing budget transparency issues and the aftermath of Ferguson.

“It’s a training that’s intended to be used for any type of issue,” said SSA student organizer Becca Clark-Hargreaves. “It’s a lot about history, and direct action in the labor movement, in the civil rights movement, etcetera.”

Recent protests associated with Ferguson, Michael Brown and Martin Luther King, Jr. Day have made it increasingly clear how popular activist movements are becoming across the country.

In the late ‘70s, a group of about 20 individuals came together under Seattle City Council to form a committee. The group, led by former Seattle City Councilman Randy Revelle, drafted the police-intelligence ordinance, which aims to protect the rights of protesters by monitoring the extent to which police can collect information on them. Unless a crime was committed, files cannot be kept on protesters.

Professor Emeritus David Boerner of the Seattle University School of Law is currently in charge of making sure that the ordinance is enforced. According to a report by King 5 News, Boerner has been auditing the Seattle Police Department’s investigative practices twice a year for the past decade and in that time has never found a violation. The ordinance has been brought up in recent conversations by the Seattle City Council and citizens who are concerned that more could be done to protect protesters’ rights. This concern stems from a recent controversy involving photographs of protesters taken by police detectives.

According to Boerner, the group responsible for drafting the ordinance ranged from attorneys, citizen activists and others involved in law enforcement, including the police.

“[Revelle] brought together all people with interest in the intelligence-gathering function of the police,” Boerner said. “There was the perception that the law enforcement agencies both here in Seattle and across the country had collected information about people…that wasn’t relevant to law enforcement needs. And so the attempt was to draw a line between criminal investigations, which no one intended to prohibit, and lawfully protected activities like protesting government for the redress of grievances or exercising religious liberty and things of that nature.”

Attempts to protect the privacy and rights of protesters can seem contradictory, as protesting is an inherently public activity.

“Obviously anyone [who’s] watching the demonstrators marching on the street [is] going to see who’s demonstrating,” Boerner said. “But the question is: should police be keeping files on who demonstrates? And the answer to that is: Unless there’s criminal activity, no they should not.”

Given that the ordinance was drafted over 30 years ago, it is a testimony to the significance of the ruling in terms of protecting citizens’ rights that it is still in use today.

“It’s still an issue, of course, and it always will be, I’m sure,” Boerner said.

Boerner said that with the changing times comes new technology that should be brought into consideration. Technological developments could make it harder to ensure that the police respect protester rights.

“You can quickly move information from one phone to another, from one device to another, to your computer, and it’s not on your phone but it’s stored somewhere else,” Boerner said. “I don’t know of any way to guarantee that that isn’t happening. I’d have no reason to believe that it is, but I don’t know how any auditor could possibly audit and guarantee that that isn’t going to happen.”

Boerner advises that when students go to protest they should both understand the demonstration’s cause and respect the law.

“That’s just common sense,” Boerner said. “Don’t commit crimes.”

Clark-Hargreaves said that a focus of the Non-Violent Direct Action Training is how to use non-violent approaches to assert protesters’ voices.

“Direct action is very much about creating some sort of event or protest or action that is sort of circumventing the ordinary paths of power that we’re taught, I think, growing up to accept,” Clark-Hargreaves said.

Mara Willaford is a University of Washington student who organizes alternative forms of resistance with a coalition called Outside Agitators 206 that fights racism.

“We believe in a diversity of tactics, and respecting different forms of resistance,” Willaford said. “We don’t communicate with the six major news outlets and we try to amplify black, trans and queer voices, because the media not only does not serve those people but is actively invested in violence against those people. In the past, we’ve held open mics and potlucks so people can just come and eat and share food together and talk about their experiences.”

The coalition also produces a bi-weekly newsletter to increase focus on the voices of people whose stories are rarely heard.

“It’s actually really important that we prioritize those stories and that they’re actually almost more valuable, because we don’t hear them very often,” Willaford said.

According to Clark-Hargreaves, alternative ways to convey a narrative will also be covered in the Direct Action Training.

“A lot of the time there are other methods of amplifying that voice through art, or through creative tactics, and I think that’s one of the things that I love most about nonviolent direct action and one of the things that’s coolest that’ll be taught in this training,” Clark-Hargreaves said. “[There are] ways that don’t involve hurting ourselves and each other, that are creative ways to get our narrative told and to get people to hear us out and understand our side of the story and to create real change in really creative and imaginative ways.”

The training will include two guest activists who will share their experience and strategies with the group.

“At a certain point your government representatives might just not listen to what you say anymore,” Clark-Hargreaves said. “Direct action is about, particularly for underprivileged and disadvantaged groups, a way of feeling empowered…this is a power we do have, and we don’t have to rely upon others to do important work for us because we can do that.”

The training will be held Feb. 7 in the Casey Commons. Reservation is not necessary, but students are encouraged to RSVP via Facebook.

Lena may be reached at lbeck@su-spectator.com