Artist Jason Hirata is known for his constantly shifting, situation-specific artworks—launching a cell phone into space, baking carbon-infused, edible black bread and creating drawings out of his own sweat are just a few of his recent projects. Since graduating from the University of Washington in 2009, Hirata has explored a wide range of artistic practices.

Jason Hirata, Seattle University’s Artist in Residence, is featured in the Vachon Gallery until Feb. 13.

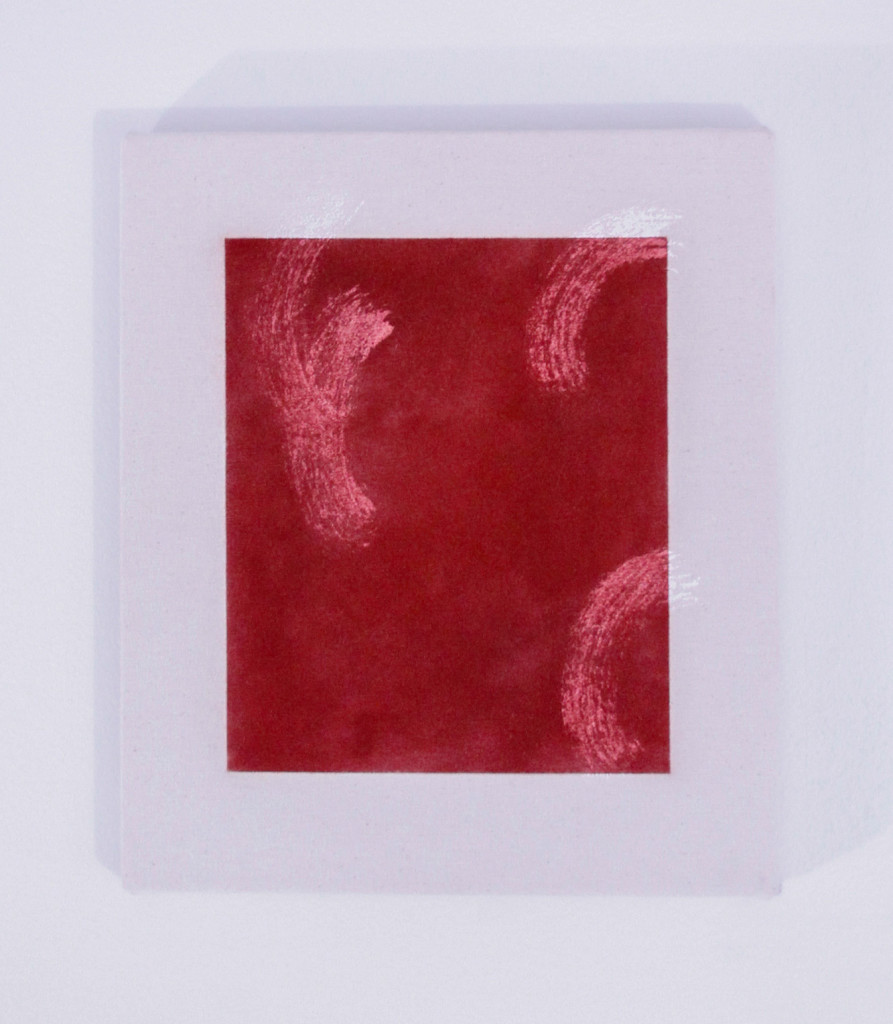

Seattle University’s Vachon Gallery recently opened its doors for the work of Hirata, who has spent the past six months as the Art and Art History Department’s Artist in Residence. Hirata has been working closely with art faculty and students across various media, and over the course of his residency he has shifted his artistic focus to include more painting.

Though much of the artwork he created while at Seattle U is currently on display in Brooklyn, N.Y., a portion of his works are on display at Vachon Gallery through Friday, Feb. 13.

CC: WHAT DO YOU HOPE TO SHOW STUDENTS THROUGH YOUR PRACTICE?

JH: What would have been useful for me as student is getting to see how at least a somewhat professional artist maintained their practice. In class it helps to have a lot of material you’re digesting and to have lots of input, so that was my main thing.

I wanted to provide the students with the materials that I think are relevant to studio art today. Originally I wasn’t sure how I was going to do that, but I got involved with the art club and was able to interface with them a lot. Eventually I realized that meeting specific students, working with them, was the main value of

my residency.

I had a lot of really good painting critiques in the advanced painting class that I felt were really generative conversations. I felt like I got to know these students’ work really well; their lines of interest and inquiry would become more apparent to me. I wanted to be more familiar with what their own individual practices were so that I could share more relevant information with them.

CC: How has working at Seattle U helped you as an artist?

JH: For me personally, it’s been really good because most artists need studios in order to work…

I actually hadn’t had a studio for about four years before I applied for this [residency], so I had a lot of saved up energy and ideas that I got to work out here.

Before coming here I hadn’t really made work for about two years, but over the past year I kind of came back slowly into making art. While I was here I felt like I had a little bit more distance from my own practice. I understood a little bit better why I’m doing art and it was more enjoyable for me.

CC: What were the inspirations for your primary work here? Did the environment at Seattle U play a role in that?

JH: I started doing more painting, which was new for me. Knowing there were painting classes here and after speaking with some of the students, I felt like it was a good thing. So on the one hand I did more painting than I think I would have otherwise—if [Seattle U’s art program] was more media focused I might have done more film and video stuff.

On the other hand, there was a long-form project that I had been working on which I got to flesh out more here, which was really heavily influenced by the institution. It was images of pre-Internet representations of art, so it started with these flat files of art from the Seattle Public Library. When I came here, it moved to just all the catalogues that are in the [Seattle U] library. So the form of that work was affected by what was actually available here.

The two main bodies of work that I did here are in Brooklyn, but I probably wouldn’t have been able to make them if I wasn’t here in

the studio.

CC: What inspired your painting specifically?

JH: I didn’t really think I could paint personally, but then I read this Jack Goldstein book. As a person, he’s really conflicted and did art for dramatic reasons; he needed art for his identity. But what I learned in seeing how conflicted he was is that he approached paintings almost like an engineer. He looked at the problem of making a painting and he engineered solutions to that. I felt like I could do painting in that way and in that framework, [then] self-expression became more straightforward to me.