On Nov. 24, Seattle University became the first Pacific Northwest school to become a fair trade university, joining 25 others across the country that pledge to support fair pay and wages for international farmers by offering their products on campus. But the journey there began more than ten years ago—and not everyone agrees that the resolution is for the best.

The ten-year journey of Seattle University becoming the first Pacific Northwest fair trade school began with coffee beans.

Rewind to the 1990s when Dr. Susan Jackels, the chemistry professor who spearheaded the effort for Fair Trade advocacy and products, became part of the International Jesuit Association of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering Universities and Schools, or ISJACHEM. At a meeting in the early 2000s, a friend named Carlos Vallejos stood up and asked for help.

“[He] stood up and said ‘We’ve got this coffee crisis going on in Nicaragua, and I think we as chemists need to do something to help these coffee farmers,’” Jackels said.

Met with no response, Vallejos made the same request the following year, threatening to quit if no one helped him.

“So something inside me just made me stand up and say ‘Okay, I’m going to help. Let’s get together. Let’s figure out what we can do,’” Jackels said. “Even without any sense of what I could do, I just had to respond because I sensed the need on his part.”

Jackels and Vallejos began working with a group of farmers. A collaboration started that lasted over ten years, including Jackels, Vallejos, university students, and a cooperative of coffee farmers in Nicaragua

called CECOSEMAC.

Using their scientific expertise, Jackels and Vallejos were able to help the farmers at CECOSEMAC to improve their coffee quality. They also undertook projects such as building an onsite coffee processing mill. With continued efforts, and returning trips, Jackels and her team also improved the roads.

“What we did benefited 13 farms; the road benefited 300 farms,” said Jackels.

“I thought they would say, ‘Oh, the scientific knowledge you imparted to us was so helpful,’ or ‘Oh, the kits that you gave us, they helped us learn what to do,’” said Jackels. “They didn’t say anything about that. They said ‘First of all you believed in us. And secondly,’ they said, ‘you kept coming back. You didn’t just do something and then leave; you kept coming back, over and over again.’ And that really woke me up as to how special this whole thing was.”

And that’s when the prospect of becoming a fair trade certified university came into the picture. At a conference on commitment to justice, Jackels and Vallejos found a flier offering a $6000 grant to a proposal from a Jesuit school. The grant required them to work toward becoming fair trade certified. The partnership with CECOSEMAC gave Seattle U a strong case, and it was chosen out of all the schools that applied.

“Frankly when we got it, I knew how we were going to help the farmers, but I didn’t have a clue how we would become a fair trade university,” Jackels said.

Back at Seattle U, Jackels asked for help. She was referred to the Director of International Business Programs Dr. Quan Le, who introduced the concept to Seattle U’s Global Business Club, led by Charlene Nayan. They started working together to form a proposal. Advised to speak with Fr. Stephen Sundborg, S.J. early on, they presented him with their basic idea. He became one of the movement’s earliest supporters and directed them to negotiate with Student Government of Seattle University.

Most of the interactions with SGSU were performed by GBC representatives. According to Jackels, both student groups were instrumental in completing the process. The first issue addressed was how to get the proposal into the formal legislative format used by SGSU. Students with Disabilities Representative Braden Wild took point on that. However, some concerns were raised once the proposal was introduced to SGSU’s Representative Assembly.

“The major concern among SGSU—and I think that [it] was fairly broadly shared—was ‘how do we make sure that once we sign this it’s not just left by the wayside and we can actually make some changes?’” Wild said.

SGSU Multicultural Representative Monica Chan brought up a concern that getting certified could result in “green-washing,” or applying feel-good labels without instigating any real change. It’s a problem she’s

noticed before.

“[It] made it easier for administrators, I think, to give a ‘no’ to divestment because they were like ‘oh, we’re already making all this progress in regards to environmental sustainability, we can just keep doing more of this, we don’t necessarily need to divest,’” Chan said.

She said that she wanted the proposal to have more teeth.

The vote was close; the resolution passed through the assembly with an eight to five vote and one abstention. Jackels and her team were also backed by her and Le’s dean, Bon Appétit’s general manager Jay Payne, and various organizations around campus.

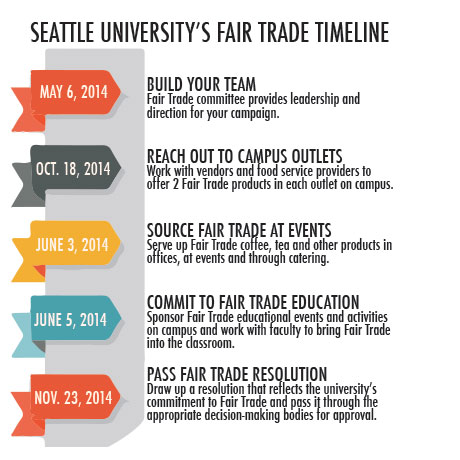

In November, with the signing of a Fair Trade resolution by Sundborg and SGSU Student Body President Eric Sype, Seattle U was designated as a fair trade university by Fair Trade Colleges and Universities USA, joining 25 other schools across the country already part of the fair trade movement.

“Seattle University becoming a fair trade campus in my opinion has the potential to be very good for our university or has the potential for us to bolster a claim that we are supporting social justice without putting any weight behind it,” Sype said. But ultimately, Sype decided to make Seattle U a fair trade university because he believes the individuals who supported this campaign will really work to improve the practices of

the university.

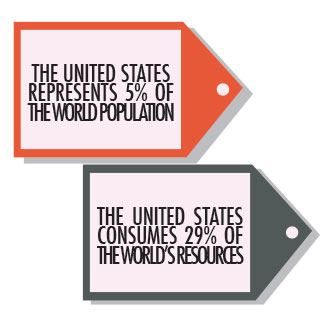

The movement intends to support fair wages for international farmers, artisans and workers. Though few would disagree with fair trade in theory, the process was hardly simple, and garnered a mixed response

across campus.

As a fair trade school, Seattle U is practicing its values of justice and human rights by pledging to have at least two products at the campus store, all eatery spots on campus, catered events, and offices—whether that’s bananas and coffee or apparel and pottery. Seattle U is also encouraged to incorporate fair trade issues into the teachings.

According to Payne, this resolution will cause them to be more vigilant about these issues. Sometimes, he said, brands will offer fair trade coffee, but then change their selection.

“The good thing about the resolution for us is that it forces us to stay on top of what happens in the coffee world,” said Payne. “Most of the other products that we have are fair trade and have been fair trade for a

long time.”

As for the Nicaraguan coffee, that’s still a long way off from being importable. But Payne says that once it’s ready, he’s ready to figure out how to make it accessible to students through Bon Appétit.

As the new year begins, the fair trade movement finds members of the campaign working on how to make the promises of the resolution materialize.

“It’s really just coming down to, how do we engage the student body? Because we’ve done all we can as their elected officials, and we’ve made it official, we’ve given it some level of awareness and attention, now it’s up to the students to partner with us,” Wild said. “It’s going to be much more of a direct student partnership at this point.”

According to Jackels, this is just the beginning.

“It’s an enabler—a springboard.”

Lena may be reached at lbeck@su-spectator.com