“The catchphrase of our generation is that we’re ‘underemployed and overqualified’ for a lot of the jobs we’re applying for,” said senior Maggie Read.

When Read walks the stage of Key Arena with her fellow seniors in two weeks’ time, she will graduate with honors and a BA in history. She wants to eventually pursue a master’s degree and become a high school teacher, but for now she’s looking “for whatever job she can get.” Right now, Read is leaning toward jobs in retail and food service that will allow her to support herself “six months, nine months, a year” down the post-grad road.

“[Working in retail or food service] should be a blow to my ego, but I’m trying to be realistic,” Read said. “I’m not alone in being a college graduate looking for work that is not necessarily directly related to my degree.” Many recent graduates across the U.S. feel the same way.

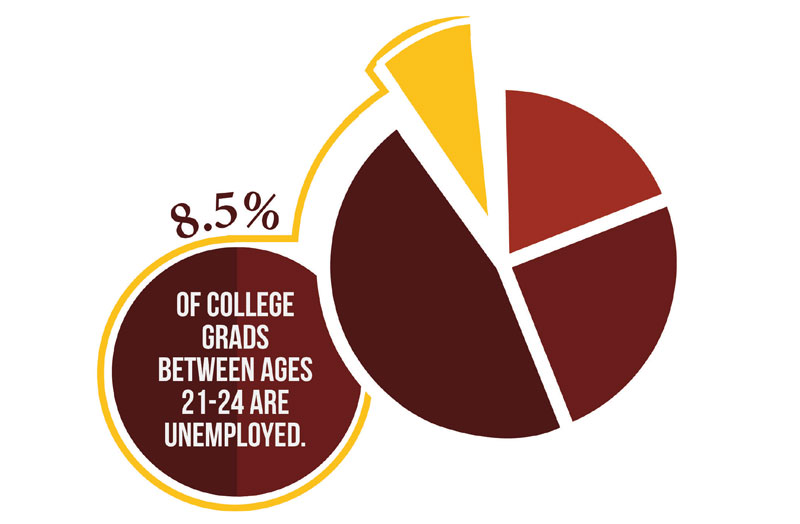

In a recent report, the Economic Policy Institute reported that roughly 8.5 percent of college graduates between the ages of 21 and 24 were unemployed.

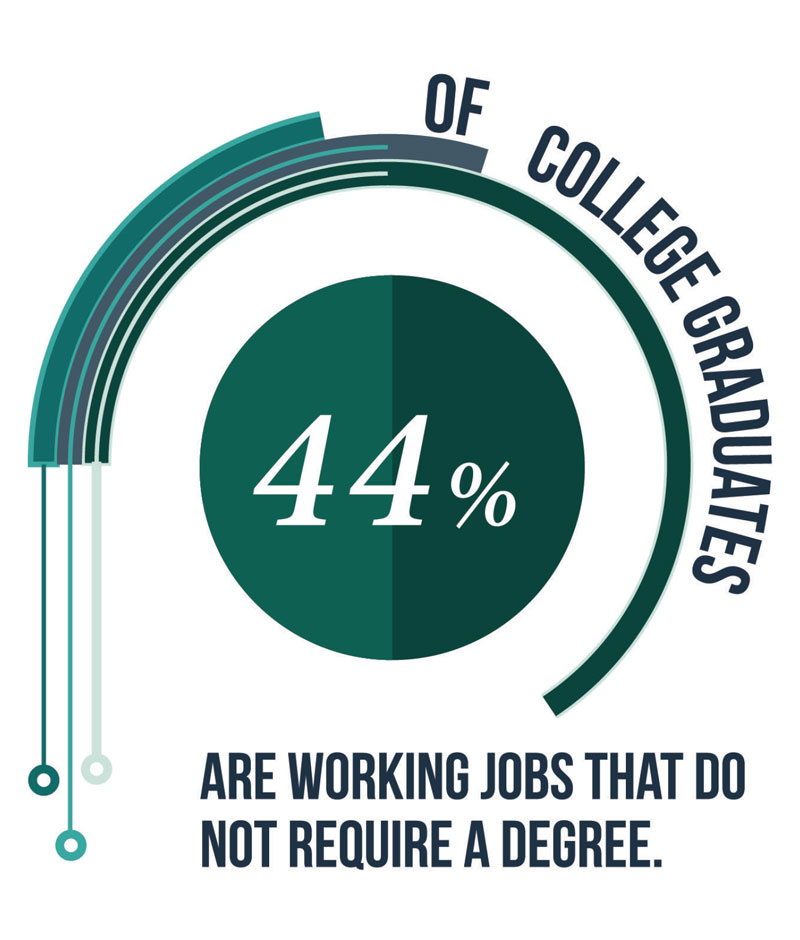

A similar report published by the nonprofit Center for Affordability and Productivity found that roughly half of those college graduates who have found employment are working jobs that do not require a college degree. That is, they are working jobs for which they are overqualified.

In an interview on National Public Radio, Richard Vedder, co-author of the Center for Affordability and Productivity report and professor of economics at Ohio University, spoke out on the issue. During the program, he argued that a high number of college graduates are working low-wage, low-skill jobs because their options are limited.

Vedder said that, instead of entering white collar, high wage jobs, graduates are “getting jobs upon graduation working as bartenders, taxi drivers—a million of them are retail sales clerks; 115,000 of them are janitors. They’re getting jobs that I’m fairly certain are less than what they expected when they began the college experience.”

This general shift toward low-income job acceptance is indicative of the current economic climate.

Many graduating Seattle U students like Read appear to be following this shift. Read estimated that about half of her fellow Seattle U graduates are pursuing jobs in their field, while the other half is just looking for jobs that will make ends meet.

Journalism major Peter Sacotte is nervous about the prospect of finding work after college.

“Retail is the hope at the moment just because I had a job in retail over winter, so I’m hoping to get back in there just to earn enough to pay rent, really,” said Sacotte.

The high number of graduating college students and seemingly stagnant number of available entry-level positions has left many young adults like Sacotte feeling like they have to enter trades that are low-salary and low-skill in order to pay the bills.

“We have four million retail sales clerks in the United States. These are not very glamorous jobs, but there are a lot of them, and those are still growing in number,” said Vedder. “[Graduates are] not all going to get jobs as scientists and managers. Some of them are going to be almost forced by the sheer numbers into these other kinds of positions.”

Bloomberg Businessweek recently rated Seattle as one of the 30 best cities in which to find work after college. According to the article, Seattle is ranked because “health care and biotechnology are major industries in the city. A variety of jobs are listed, from a post for a sous chef to one for a software development manager at Amazon. Relatively low unemployment and high average annual pay are attractive benefits for recent college graduates.”

The article also noted that Starbucks is the largest employer in Seattle, but while baristas are people too, someone with a theology or social work degree might not feel too happy about serving Frappuccinos fresh out of college.

In another article published by the Wall Street Journal on MarketWatch.com, Seattle is listed as one of the top 10 cities to live in as a college graduate. The article stated that “college graduates are flocking to Seattle in favor of the enticing combination of work and social possibilities.” But as Seattle’s population grows, open entry-level positions are likely to become more and more competitive and less and less common.

The reality is that finding a quality job right out of school, whether you’re in Seattle or not, is difficult. However, there are many students at Seattle U who have had luck securing jobs in their field.

Accounting major Chelsea Schmidt was offered a full-time accounting position at the company which she has been interning part-time at for the past year. She will continue working there while preparing to participate in the MPAC program and earn her CPA through Seattle U next year.

Sarah Thomson, the associate director of external relations at Seattle U Career Services, regularly works with students to help them develop resumes and find job opportunities in a variety of professional fields, although it is easier to find a job in some fields than others.

“We know in general that engineering, business and nursing students have higher starting salaries than other graduates, just because of their technical skill set,” said Thomson.

Biology major Kristine Aggabao said that although securing jobs is dependent on the way a person markets themself, being in the science field grants her more potential in securing a job.

“Does being a science major give me kind of a leg up in the world given the idea that science is something that is applicable? I think it does give me an edge,” Aggabao said.

Sacotte expressed the same sentiment, observing that it’s more difficult for graduates with liberal arts degrees to find work after graduation.

“I feel like all of my engineering friends already have jobs that pay unbelievably well. One of them has a job—I don’t know if he’s quite getting six figures, but it’s close to a six-figure salary—one year out of school and he gets to travel the world. He has gone to Italy, he has gone to Thailand. He was in California two weeks ago. He was in Florida two months ago … like what? I want to do that. But I feel like that will never, ever happen with my degree,” Sacotte said.

Similarly, graduating marketing major Margaux Helm said she feels like many of her peers in the Albers School of Business and Economics have already found jobs.

According to Thomson, students with more specific or skill-oriented degrees tend to be more direct in their approach to the job market, while those students more concerned with the humanities often need to take more time to explore the market and discover what works for them.

“At Seattle U and nationally it takes arts and sciences students a bit longer to work their way into high-income vocations or positions, but that’s mostly just because there tends to be a greater variety of career paths for those students,” said Thomson.

Still, paid employment is not the only door left open to young adults following graduation. Many students choose to volunteer their time and energy to groups like the Peace Corps and the Jesuit Volunteer Corps. A survey conducted by Seattle U found that about 3.6 percent of surveyed graduates from the class of 2013 have taken some form of volunteer position with groups like these.

Senior Victoria Richey, a psychology major, talked about the difficulty of entering the job market right out of college, and how this sentiment contributed to her decision to join the Jesuit Volunteer Corps (JVC).

“I knew I was neither qualified nor interested in immediately getting a job that was related to my major. I think a lot of seniors, recent grads can identify with these feelings,” said Richey. “I think many don’t feel extremely qualified with only a Bachelor’s degree, and because graduate school means a lot more [money] to shell out and a lot more scholastic energy, undergrads may be hesitant to jump right into a masters or into their desired career path.” Richey will be working with the East Bay Community Law Center in Berkeley, California through JVC.

Fellow teaching major Catherine Riviello will also be entering a one-year service mission with the JVC after graduation.

“I really love Seattle U’s mission for social justice—being men and women for others—and I really wanted to live that out. So I decided to joining the JVC as opposed to going straight to grad school after graduation,” said Riviello.

Riviello will be heading to New Orleans at the end of the quarter, working as an elementary school teacher at a charter school.

“I hope to learn more about myself and what it is I envision my future looking like. I’m really excited and scared at the same time to not be in school, just because I’ve been in school my whole life and I know that school is something that really grounds me,” Riviello said. “Further, being away from friends and family, in a new place where you are completely accountable for your actions, is exciting and scary at the same time.”

But what about those students who can’t manage to do anything after graduation? According to the report published by the EPI, “a total of 16.8 percent of new grads … are either jobless and hunting for work; working part-time because they can’t find a full-time job; or want a job, have looked within the past year, but have now given up on searching.” This is a scary prospect and while the job market may be on the uptick, it’s obviously not back to normal.

Despite the statistics, many Seattle U students are still looking forward to their graduation date just two short weeks away. Whether she finds a position in retail or her dream job, Read is optimistic about the opportunities available to her.

“I’m hopeful that I’ll be able to find work,” Read said.

Others are less convinced. Sacotte, although excited to escape the college routine and move on with his life, will miss the comfort of Seattle U.

“I’d like to be in school forever,” Sacotte said. “Then I wouldn’t have to worry about finding jobs.”

Will may be reached at wmcquilkin@su-spectator.com