Elliot Rodger thought he was entitled to a woman’s love. So much so, that he killed for it. The 22-year-old made national news this week after he allegedly murdered six people, injured seven, and then killed himself at the University of California Santa Barbara. In one of several Youtube videos he left behind, Rodger explained that he killed in an act of revenge against women. He wanted them, and they should have wanted him back, he said.

For thousands across the globe, his actions are an example of the daily objectification and harassment of women. In response to these events, the #YesAllWomen hashtag has been used over 1 million times to raise awareness of and change the dialogue surrounding sexual assault. The campaign has united women across the globe, allowing them to share their stories of harassment.

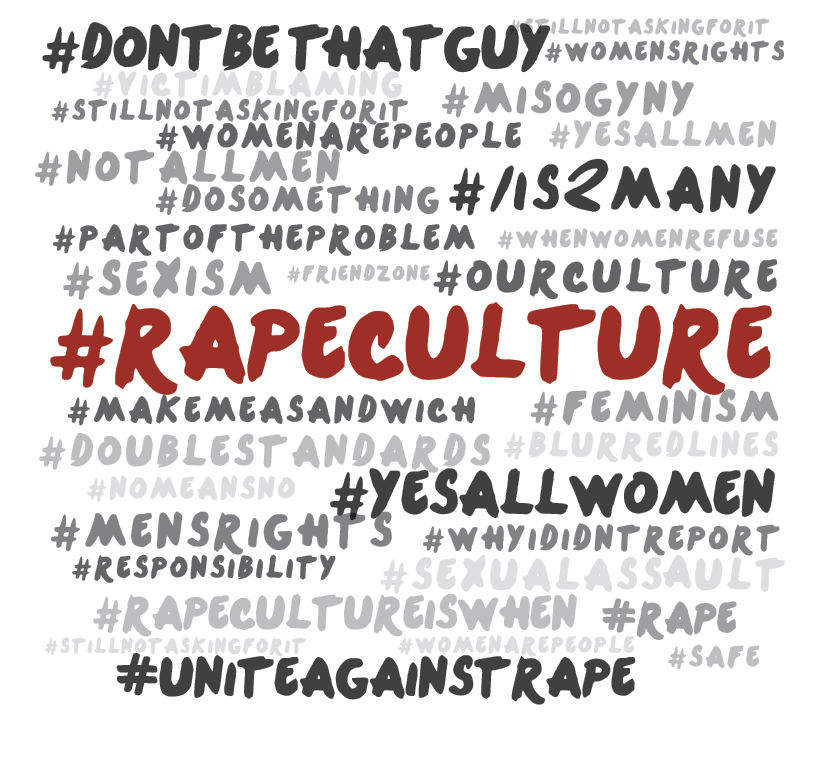

#YesAllWomen is the latest Twitter hashtag to spark nationwide discussion on the epidemic of violence against women. On a deeper level, the campaign is challenging an endemic rape culture—where victims are blamed for the assaults against them, perpetrators are often able to continue offending, and the few who do speak out are regularly silenced. Unlike those before it, however, this hashtag has seemingly pervaded the mainstream, engaging men in the critical conversation.

One of Time Magazine’s May cover stories featured this topic, including some of the most retweeted of #YesAllWomen. These include:

“#NotAllMen practice violence against women but #YesAllWomen live with the threat of male violence. Every. Single. Day. All over the world.”

“Because society is more comfortable with people telling jokes about rape than it is with people revealing they have been raped.”

“#YesAllWomen because when women stand up for their right to feel safe & not get killed or raped, men turn it around & make it anti-male.”

“Because I’m tired of having the humanity of women recognized only after something inhuman is done to them. #YesAllWomen.”

The hashtag is a response to #NotAllMen, a hashtag that debates the pervasiveness of patriarchy in Western culture. Those using the latter hashtag argue that not all men are harassing and assaulting women. But many have expressed frustration with the #NotAllMen thread for many reasons, including that the feed is a defensive response that continues to ignore the fact that women are still facing these issues on a daily basis.

“No, not all men channel frustration over romantic rejection into a killing spree. But yes, all women experience harassment, discrimination or worse at some point in their lives,” wrote CNN reporter Emanuella Grinberg in response to the Twitter feeds.

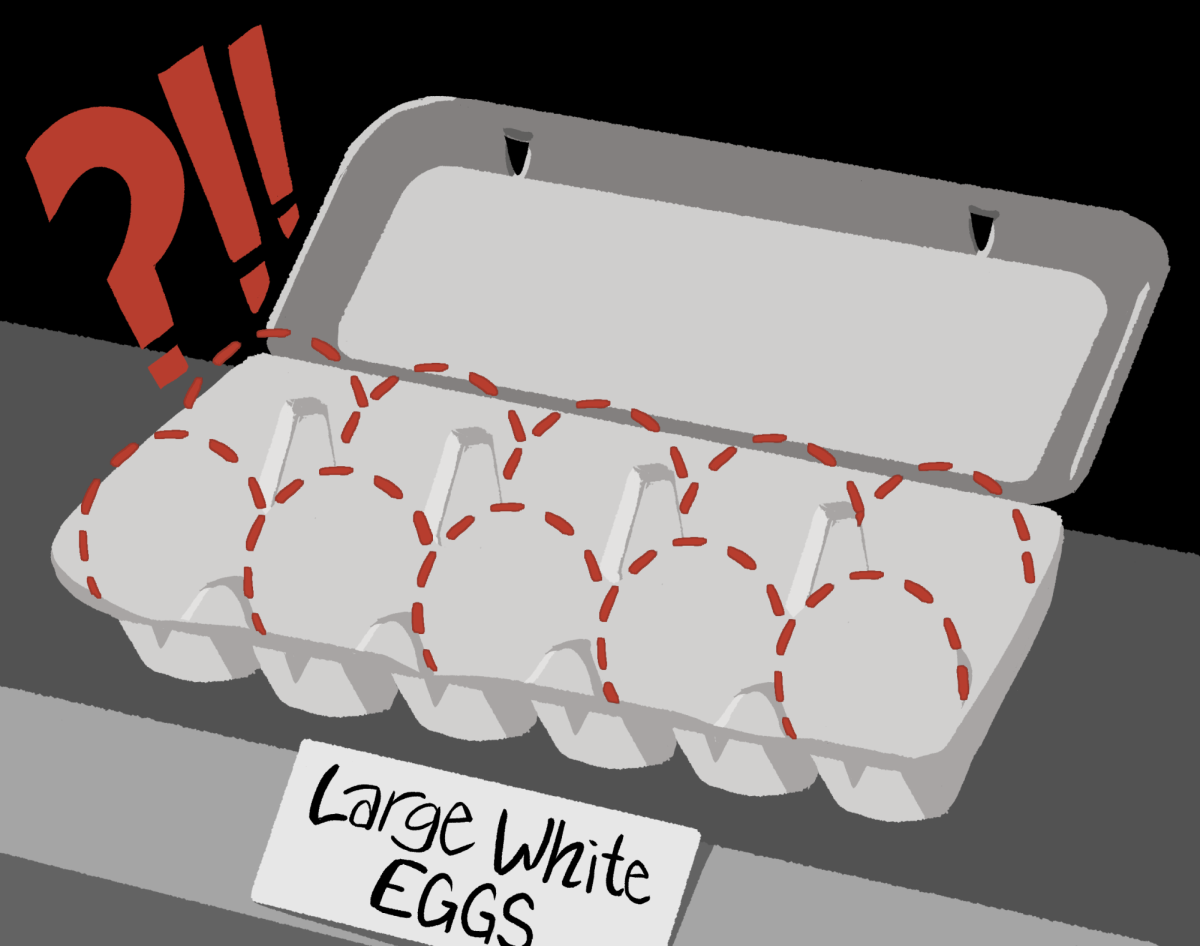

For many, the shootings at UCSB are a startling reminder of culturally instilled misogyny. In the last few years, several attempts have been made to redefine the disturbing reality of sexual assault. Most recently, President Obama and Vice President Biden launched the “Not Alone” initiative. As a subset of the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, this initiative is designed to ensure the protection of, and support for, sexual assault survivors on college campuses. “Not Alone” calls for the engineering and mandating of supportive legislation that advocates awareness, provides information and resources to students and schools to prevent sexual assault on college campuses.

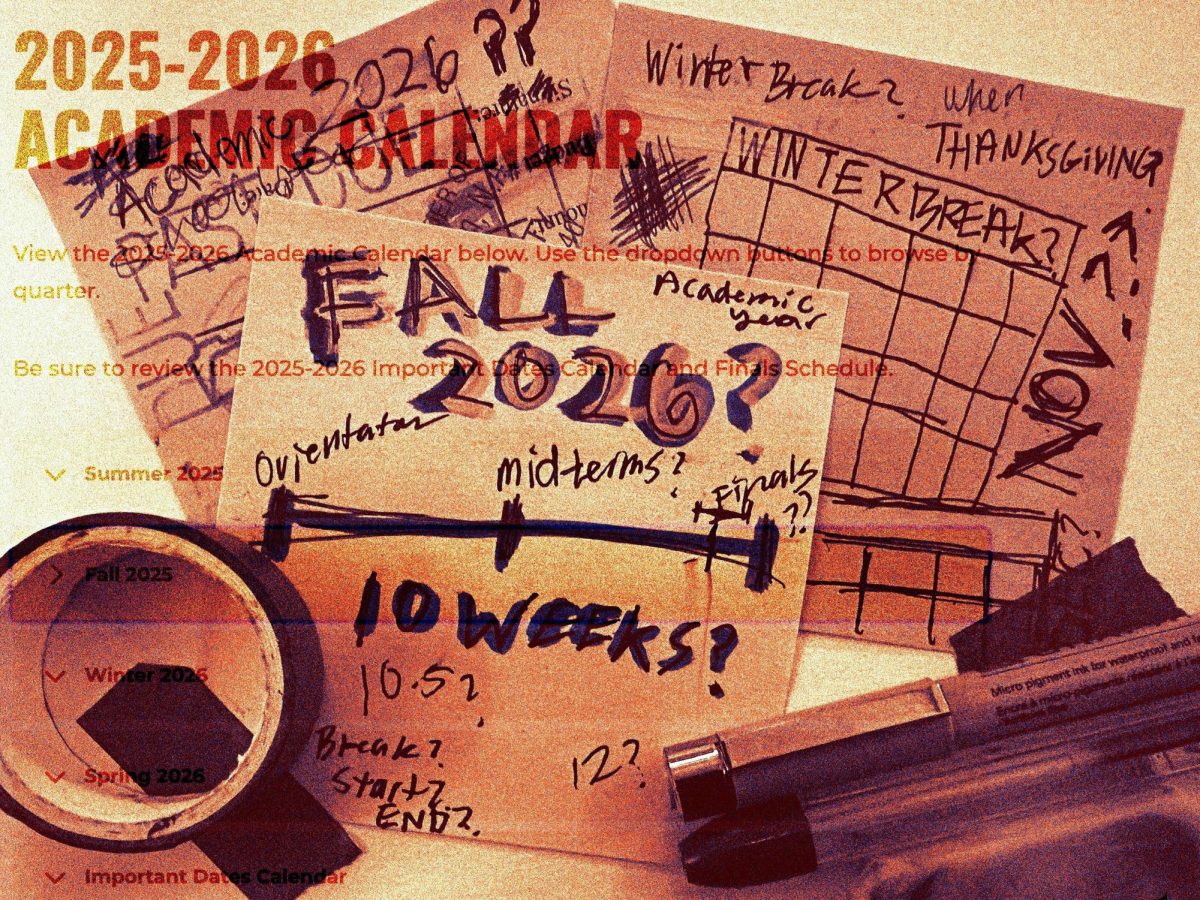

In keeping with the Task Force’s suggestions, but prior to #YesAllWomen, Seattle University, too, has asserted the promotion of dialogue around sexual assault education and awareness.

Earlier this month, Seattle University Director of Health and Wellness Ryan Hamachek explained to The Spectator that he had organized a men’s group designed explicitly to discuss sexual assault.

Additionally, various student groups have been either elected or chosen to sit in on student conduct PowerPoint presentations facilitated by the Division of Student Development that address sexual assault, alcohol and drug use. Known groups to have attended the presentation are Student Government of Seattle University (SGSU), Resident Assistants, Resident Housing Directors, Alpha Kappa Psi and the university choirs.

Though the presentations were timely given the national efforts to improve education in this area, the undeniably well-intentioned presentations sparked controversy as some attendees were left angered by the topics covered. Some students expressed concerns that the presentation bordered on implicit victim blaming. The phrase “victim blaming” is used to recognize when the victim of a crime is held or seen responsible for the offense. The victim blaming phenomenon has enormous implications, particularly when discussing the reporting of sexual assault—due to blame, victims have been shown to feel guilt for events they did not cause. Some felt the Seattle U presentations furthered this message.

“I was upset to see that, in a presentation that was framed to me as a sexual assault seminar, that there was also this element of information about alcohol and impairment and going out in groups,” said senior Rima Kaboul, who saw the presentation both as a member of choir and as an RA. “If you want to educate people about the adverse effects of alcohol and about safety, that is fine, and I can see the value in that, but it didn’t seem like it was in the right place. Because even presenting them in an unclear way, together with sexual assault is an implicit way of victim-blaming.”

But Joy Sherman, choir director, lauded the presentation for its breadth.

“It was broader than just sexual assault…It’s a very broad and effective presentation and everybody needs to see it,” she said.

These presentations are not the only move by Seattle U to address issues of sexual assault on college campuses. Last year, The Spectator published an article that addressed the university’s then-recently updated Code of Conduct, as well as the creation of a new conduct board called the Sexual Offense Review Board. Reporter Kellie Cox explained in that article that the adaptations made to the school’s policy were enacted in response to a document from the U.S. Department of Education called the Dear Colleague letter, which the school received in 2011. The Dear Colleague Letter recommended that universities reconsider their current processing of sexual offense cases and hearings.

The new Code of Conduct rewrote Seattle U’s definition of consent, provided a list of guidelines designed to help students avoid situations that could result in sexual offense, reporting procedures and a general overview of the student conduct process.

However, some students who went through the newly adapted process last year expressed frustration. They varyingly cited neglect, poor communication, insensitive questioning, drawn-out proceedings and inappropriate hearing procedures relating to the dynamic between the victim and alleged aggressor. During the presentation given to choir earlier this year, one student raised her hand and asked what students should do if Public Safety does not take a report seriously—another example of students expressing doubts about Seattle U’s sexual misconduct procedures.

Earlier this month, Dean of Students Darrell Goodwin opted to withdraw his interview with The Spectator regarding these presentations. The Spectator was then unable to conduct a second interview due to miscommunication and Goodwin declined to further comment at the time of publication. Goodwin also declined to send a copy of the presentation.

In response to the presentations, Monica Nixon, who serves on the Sexual Offense Review Board, said the university has been working to improve its education methods.

“We are stepping up our education efforts. We could always do more with that,” Nixon said.

Similar presentations have continually been reaching a larger audience. On Monday, May 27, Student Development delivered a presentation to female student athletes; the men’s presentation followed a week later. The student athletes were separated by gender and shown what appears to be a similar, but not identical presentation—male athletes were provided with extra materials focusing on how men can involve themselves in violence prevention.

Recently, posters from the “Don’t Be That Guy” campaign have also appeared on campus. The images of the “Don’t Be That Guy” campaign focus on behavior, namely of men, to remind everyone that sex without consent is sexual assault. The goal of the campaign is to encourage people to take responsibility for their actions, therefore removing blame from the victims of these assaults. Though the “Don’t Be That Guy” campaign has been applauded for its efforts to educate potential perpetrators rather than victims, some have also accused the campaign of touting a heteronormative bias and employing scare tactics.

Regardless of the method, the conversation on sexual assault is getting louder among campuses nationwide. Columbia University recently made national news for its powerful response to the administration’s meager attempts to address the sexual assault epidemic on campus. A student group called “No Red Tape” tagged monuments, signage and even their college graduation caps with red tape in protest of the university’s insufficient action. The tape acted as a symbol of silence—an image commonly associated with assault victims.

The discussion surrounding sexual assault came to the forefront of Columbia University when a list of names described as “sexual assault violators on campus” appeared on women’s bathroom walls on May 14. Quickly washed away by university janitorial staff, fliers were next spread across the campus listing the same four names of the alleged “Rapists on Campus.” The fliers asserted that three of the men had been found “responsible” by the university for sexual assault and described the fourth as a “serial rapist.” All individuals on that list remained unprosecuted.

In response to the perceived injustice, 23 students filed a complaint with the Department of Education, citing violations of Title II, Title IX and the Clery Act against Columbia and Barnard College, the affiliated women’s school.

The complaint stated that the university “discouraged students from reporting sexual assaults, allowed perpetrators to remain on campus, sanctioned inadequate disciplinary actions for perpetrators and discriminated against students based on their sexual orientation, according to a statement from the students who are calling themselves Our Stories CU.”

Nixon said the response to sexual assault, from the U.S. capitol to college campuses through the nation, have shown that colleges aren’t getting it right. Historically, these issues go underreported and people are making that point loud and clear.

“What the Department of Education and others in the federal government—senators, Vice President Biden—[are] responding to is more than two decades of student activism saying ‘Colleges don’t do this well,’” she said. “The guidance that they are providing is saying, ‘We will not stand for this anymore. Colleges must address culture of sexual assault, rape culture. Colleges must address these issues. When we hear about sexual assault, domestic violence, dating violence or stalking, we can’t just deal with them informally, or sweep them under the rug, which is what has happened on college campuses for a long time.’”

*This article was corrected and updated on June 4, 2014.

Cinda K. Lucas

May 28, 2014 at 11:33 pm

Brilliant and well thought out analysis of a troubling topic facing women today. When it becomes not OK to speak disparagingly about women and instead show respect is when the culture will change.