University President Fr. Stephen Sundborg, S.J., believes that Seattle University is a religious institution more than it is a place of learning.

Sundborg and other university administration officials, like Provost Isiaah Crawford believe this so ardently that they have devoted hours testifying to this effect in front of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in recent days.

As The Spectator reported last week, the NLRB has been called to monitor an election that would decide the unionization of adjunct/contingent faculty under the SEIU umbrella. Seattle U administration, which has sternly urged these faculty not to affiliate with SEIU, responded by challenging the jurisdiction of the NLRB in this matter by citing religious exemption as a predominantly Catholic institution.

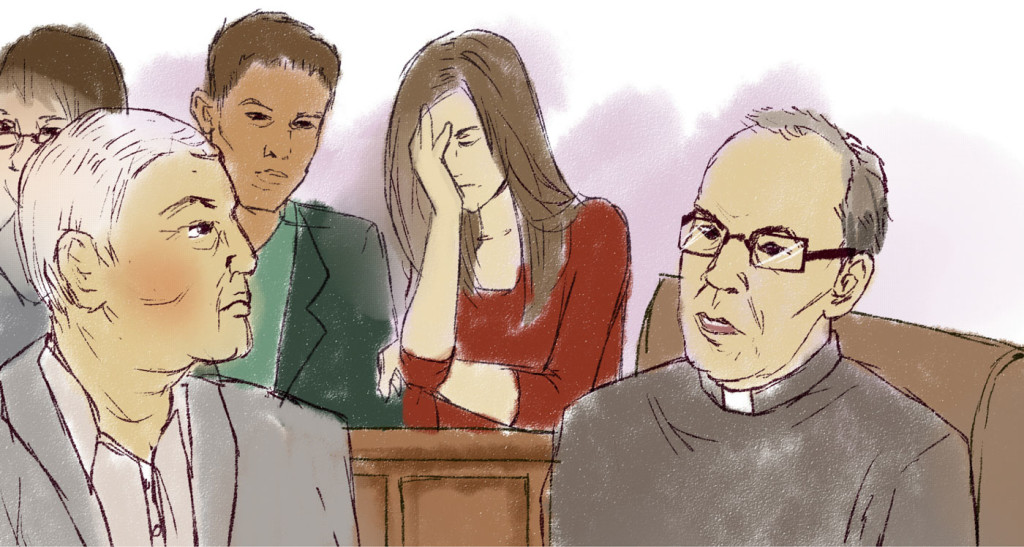

Michael Lynch, defense attorney for Seattle U’s administration, kicked off the hearing by calling Sundborg to the witness stand at the second NLRB hearing on Friday, March 7. The small courtroom was nearly full with observers. As Sundborg moved to the front of the room, some in the peanut gallery appeared to adopt grave expressions while others seemed almost giddy.

Your administration isn’t Catholic, your board isn’t Catholic, your faculty isn’t Catholic and your students aren’t Catholic, “How can you call yourself a Catholic university?” Lynch asked Sundborg.

Sundborg smiled knowingly and began his defense by referencing the criticisms SEIU has employed in undermining the university’s application of its religious roots. Sundborg explained that Jesuit education does not like to separate the secular from the sacred; he said the sacred can always be uncovered.

“We treat all people as having a religious dimension,” he said. In arguing for the inherit “Catholic-ness” of Seattle U, Sundborg recounted a speech he delivered at the Provost’s Convocation in 2008, which he called “the most significant address he’s given.” In the address, Sundborg declared the importance of an “open circle” and “knowledgeable conversation” on the Catholic tradition and its intellectual dimensions. Sundborg argued that dialogue like this is “the heart of our academic engagement with one another and with our students.”

Sundborg also referenced to the core curriculum to bolster his arguments. In particular he implied that the requirement that students take two courses in theology and religion, including a class that discusses the Catholic tradition specifically, strengthens the university’s case.

Sundborg also referenced the question he believes an important one to ask of all in the university community: “Why do you want to be in a Catholic university?”

Sundborg explained that an individual’s answer to this question is often a huge determining factor in his hiring decisions, particularly those in managerial roles like department deans. He said that a dismissive reply of, “I’m comfortable with it,” is something that he actively seeks to avoid. As part of his case for Catholicism, he also fervently expressed his desire that the university’s mission (rooted in Jesuit philosophy) inspire all educators, administration and students in the content of their teaching and learning.

Sundborg, however, did note in cross examination that Seattle U does have a policy of “academic freedom” and that the only thing that faculty are not permitted to do is misrepresent Catholic teachings.

Furthering his case for a supremely Catholic Seattle U, Sundborg also (at Lynch’s prompting) pointed out that there is a significant physical Catholic presence on the university’s grounds.In particular he referenced the four chapels on campus, the George Tsutakawa fountain and buildings named for notable theologians.

Meanwhile, as hearings and conversation continues, some adjunct faculty have actually come forward expressing their hesitancy toward involvement with SEIU in recent weeks.

“If I wanted a full-time job as a university professor I could go to another university in another town but I have the made the choice to want to work here at Seattle University […] I don’t think that I need the union at all to work on my behalf,” said Joe Barnes, adjunct lecturer in the Albers.

Monday’s hearing lasted for over six hours. Sundborg’s testimony began with an extensive chronicle of his early education and childhood, prompted by Lynch’s digressive questioning. He addressed his impressively large collection of philosophy, theology and ecclesiastical degrees and, hand-held by Lynch, regaled attendees about his post-seminary school dreams of returning home to Alaska and working as the town priest. Lynch also prodded Sundborg, who is somewhat renowned in the University community for his verbosity, into recounting a typical day-in-his-life and speaking about his vows of chastity, obedience and poverty.

This autobiographical narrative was punctuated by hems and haws from some spectators. Those seated furthest from Sundborg muffled some not-so-subtle aggravations into their clenched fists as the testimony dragged on.

The line of questioning was eventually interrupted by an objection from SEIU attorney, Paul Drachler who called Sundborg’s testimony, “Interesting, but irrelevant.”