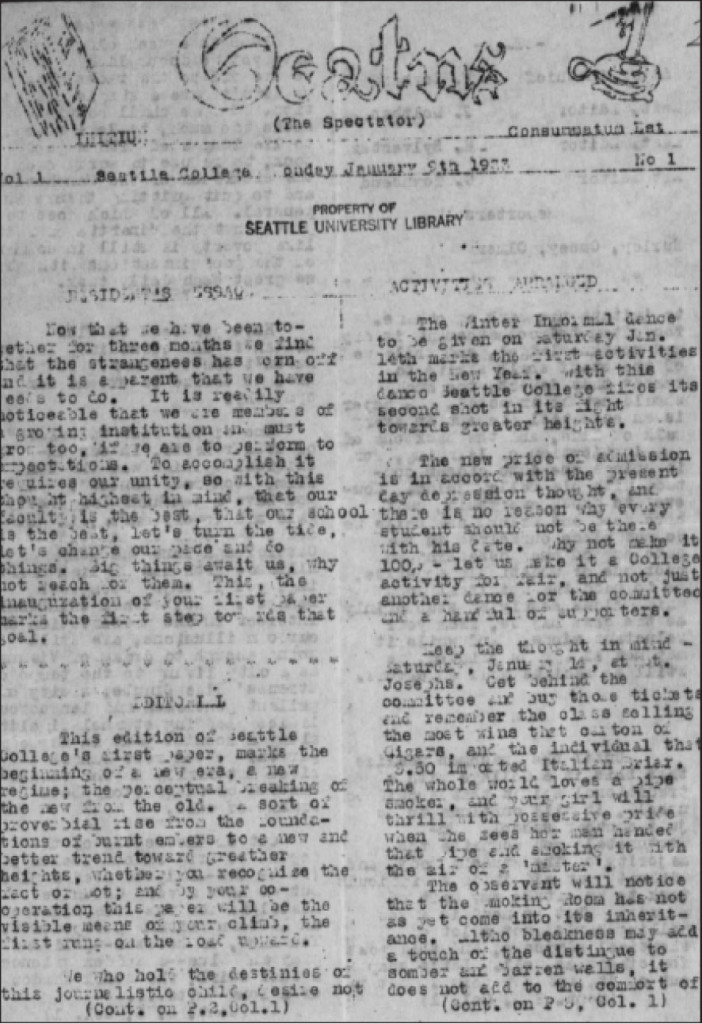

Turn back the clock 80 years to 1933. That was the year Seattle University’s student newspaper first came to be.

There were three articles featured on the cover of The Spectator’s first issue, which was distributed on January 9, 1933. The first was a message from the university president outlining his goals for the year and the second announced plans for a winter dance that would ring in the New Year. The final cover story was an editorial introducing the school’s new publication.

“This edition of Seattle College’s first paper marks the beginning of a new era, a new regime; the perceptual breaking of the new from the old,” read the editorial. “This paper will be the visible means of your climb, the first rung on the road upward.”

It seems The Spectator had perfect timing—that first 1933 issue began documenting “the road upward” just as the university was pulling out of the driveway.

From the late 1920s to early 1930s, the student body of Seattle College leapt from just 46 students to more than 500. It was a time that would see the creation of the school’s first student government organization, the Associated Students of Seattle College, and the university’s first yearbook, “The Aegis.” By 1933, the school allowed women to enroll in “night classes,” making it the first coeducational Jesuit institution in history. In the midst of the Great Depression, the institution found its footing and became a well respected university just before the onset of World War II.

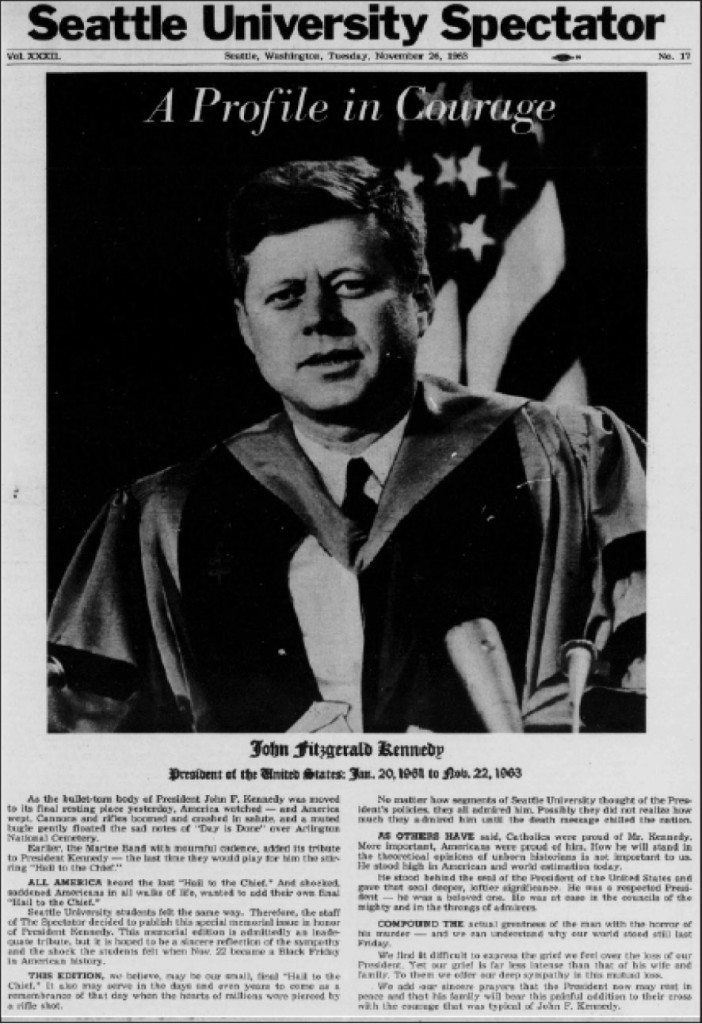

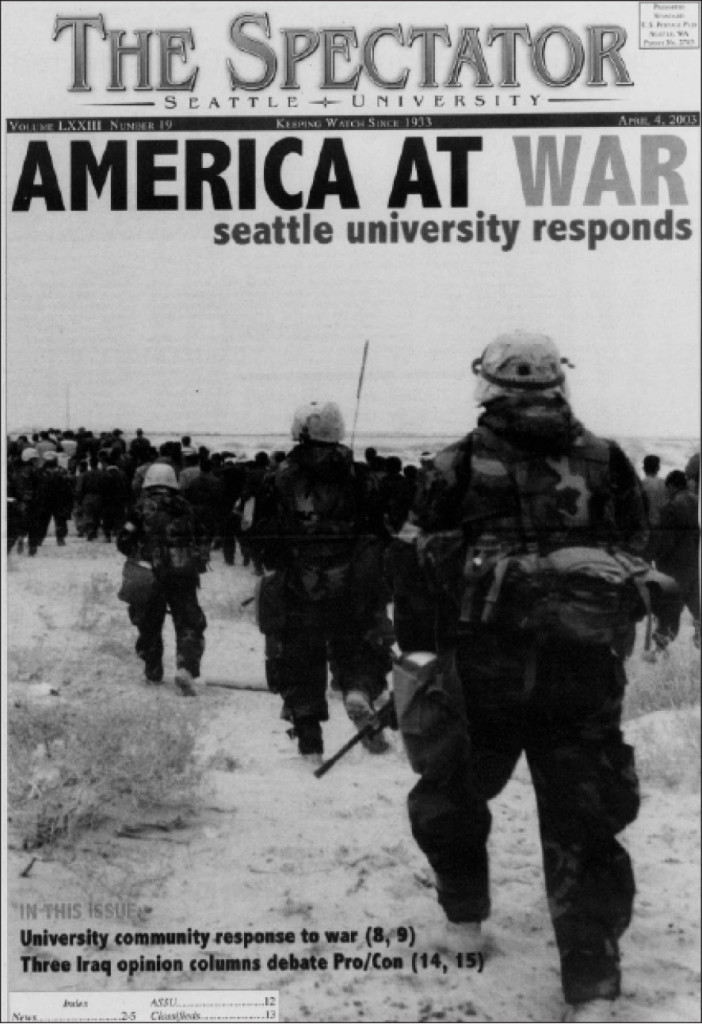

In its 80-year lifetime, The Spectator has covered national and local events, spread both good and bad news, and sparked a handful of conversations, as well as controversies.

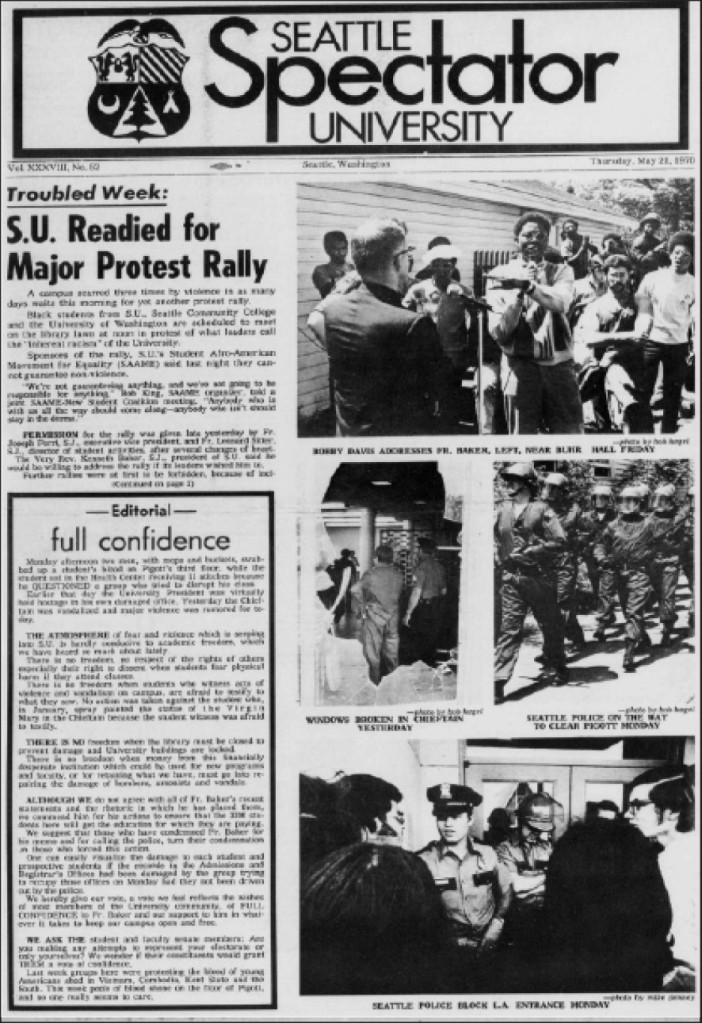

During former editor-in-chief Don Nelson’s time on staff, The Spectator covered the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and reported on turbulent Civil Rights protests on the Seattle U campus.

“It was a very tense time,” said Nelson of the social and political atmosphere during his tenure. “You wondered who was going to get shot next.”

A lighter milestone for the city of Seattle arrived in 1979, when the Seattle Supersonics won the NBA championship. The Spectator covered the win during former editor-in-chief Teresa Wippel’s time as editor.

Since Seattle U is a private, Jesuit university, it is perhaps difficult to determine the role of a student publication. At some points in its history, The Spectator aimed to be campus watchdog—during the ‘80s and ‘90s, the paper’s tagline was “Keeping watch since 1933”—and at others, it was primarily a form of university publicity.

Toeing the line between freedom of the press and the paper’s affiliation with the institution has always been a struggle for its staff.

“One thing that is really interesting to watch is to see how much independence The Spectator has,” said David Madsen, an associate professor in his 33rd year at the university and a long time reader of the paper. “The Spectator is a public face of the university and [Seattle U] feels protective of their reputation. It’s interesting to see how it works out.”

The Spectator has stirred up a number of controversies in its 80 years at Seattle U. During Wippel’s tenure, an article about birth control sparked a backlash from the community.

“It caused a firestorm of controversy among the traditional Catholics and alumni at the university,” said Wippel regarding the piece.

In the 1960’s, the publication pursued a few scandalous stories that uncovered corruption within student government.

“My junior year, the [student government] set up a credit card with a fine dining club,” said Mike Parks, who was editor-in-chief at the time. “Without letting anyone else know, the student officers went to these nice restaurants and charged meals. The Spectator exposed them.”

A later story revealed that the government had been using university funds to purchase clothes and, during Nelson’s tenure, the student government actually threatened to cut funding from the paper.

According to former faculty adviser Tomás Guillen, The Spectator was embroiled in a number of controversies in the late 1990s and early 2000s as well. When The Spectator reported that an athletics employee might have been forced out of the university, the administration took offense and sought a retraction. Guillen said the administration asked him if he had an attorney. Eventually, the school made the editors shut down the paper’s new website. Although the site was live again shortly after the shutdown, the event lead to Guillen’s resignation from his post as faculty adviser. He felt the university was trying to censor the paper.

In another administrative run-in during Guillen’s time as adviser, the provost accused The Spectator staff of stealing*, although the statement was never proven and legal action was not pursued.

Whether the story is controversial or mundane, the paper has tried to stay up-to-date since its creation. Today, the paper comes out every Wednesday which was a change made in 1976. Prior to that year, the paper actually came out twice a week, every Wednesday and Friday.

“It helped us stay more current,” Nelson said.

Now that the paper is only published once a week, some at the university feel it is more difficult to keep up with relevant news. Madsen feels that a weekly newspaper is not a good strategy.

“It has become less of newspaper,” said Madsen. “The arts and sports are still the same, but a lot of articles are not so driven by newsworthiness as they are by general interest stories.”

But whether the articles are deemed newsworthy or not, the primary purpose of The Spectator has always been to inform its readers about what is going on at and around Seattle U.

A number of technological advancements over the years have changed the way the staff goes about its mission to inform. For many years, The Spectator did not have all the publishing, layout and design advantages it has today.

“Putting the paper together was pretty clumsy. We still had typewriters and the term ‘cut and paste’ was literal,” Nelson said.

Prior to the digital age, everything was written with typewriters and all pictures were developed in darkrooms. Laying out the paper meant sticking several pieces of paper together and on top of each other. Today, an error can be fixed in a second. But back then, not so much.

“If you changed a word, the whole thing had to be redone,” Parks said.

With a slower layout process, former Spectator staffers likely had to work harder to turn out a paper than today’s editorial board.

“It was a full-time job,” Wippel said. “I remember working 40 hours a week and managing my classes.”

Another major change to the paper over the years has been its design. In The Spectator’s early years, the paper was primarily made up of text, with few photos and a traditional style. Articles began on the front page and were continued on other pages of the paper. Not to mention it was completely black and white.

Today, The Spectator has a more offbeat design. It is colorful—color was introduced to The Spectator during Guillen’s time as adviser—and formatted more like a magazine than a traditional newspaper.

Regardless of its appearance, The Spectator’s primary goal has remained the same across: to deliver news to the community. It hasn’t always succeeded, and it has ruffled some feathers along the way, but its presence has remained constant.

“Since The Spectator is a public face of the university, it should be something that they are proud of and frankly something we can all be proud of,” Madsen said.

Several former editors expressed their pride in the paper and its history. The Spectator’s legacy is one they helped create.

“There is nothing like putting out print and having people read it,” Nelson said. “It is ultimately a profound thing.”

The editor may be reached at editor@su-spectator.com.

*Editor’s Note:

Professor Tomás Guillén—interviewed for the article “Celebrating The Spectator’s 80 Years in Print”—would like to clarify that, during his tenure as faculty adviser for the paper, the provost accused the staff of stealing a document that had been leaked to them.