Former student Jordan Meyers didn’t fit in at Seattle University. The school was already difficult to afford—Meyers had to take out a number of loans to pay for his education—and, as a freshman, Meyers felt disconnected from the personality of the school. It was a problem large enough to merit a transfer and, in 2012, Meyers left the school for financial and personal reasons.

“I didn’t feel that I fit in at Seattle University. I’ll say that I think all schools certainly have their own personality and culture, and I think some students click with those personas, and some don’t,” Meyers said.

Every year, high school seniors go to great lengths to find the college that’s right for them. They compare programs of study, cost, class sizes, the surrounding community and more. Once they find that perfect school, most people stay there until they earn their degree. Students like Meyers, however, are not so lucky— they feel they have made the wrong choice or that they cannot afford to continue with their education and ultimately choose not to return.

Seattle U wants to reach out to those students and understand their plight before it’s too late. In order to keep more students like Meyers from leaving the school, Seattle U has created a new position dedicated to improving its retention rate.

Earlier this year, the administration welcomed Josh Krawczyk, the new director of University Retention Initiatives. Krawczyk is determined to keep as many Seattle U students from transferring or dropping out as possible.

“Retention is everyone’s concern, but before [my position was created],nobody owned the responsibility for it,” Krawczyk said. “I am a department of one that partners with offices and divisions to see the strengths they offer in supporting students and find what they can do more and what they can do better. A lot of data is captured on the undergraduate side and we have just begun gathering data on the graduate and transfer side.”

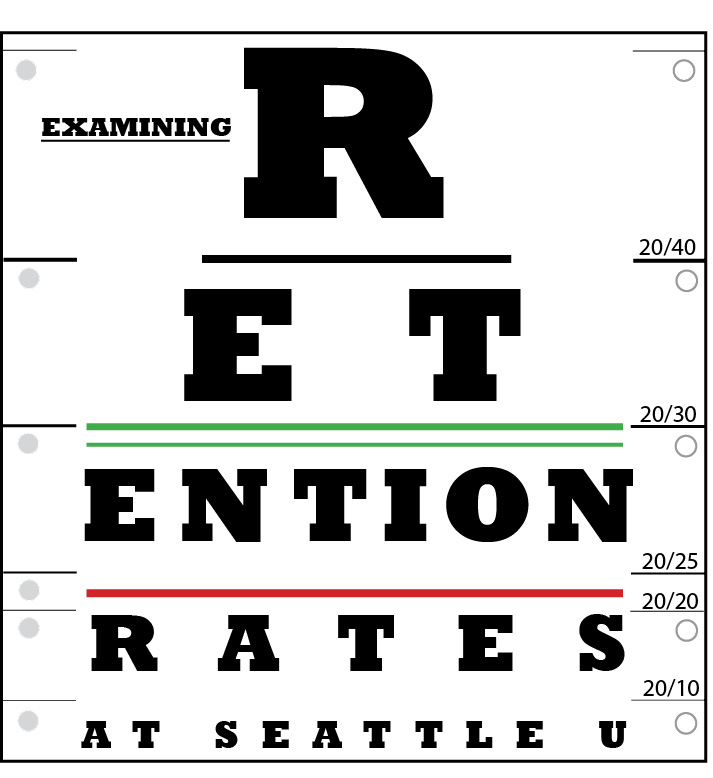

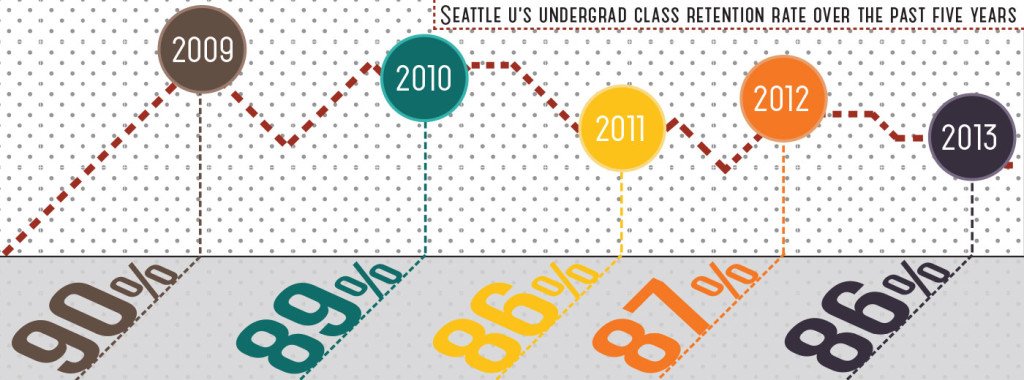

Seattle U already has a high retention rate. The freshman classes over the last five years have had retention rates of 90, 89, 86, 87, and 86 percent, respectively. Although the number is dropping, it is important to note that incoming class sizes have been increasing. The number of returning students has remained largely consistent thus far. The average rate of returning graduate students over that same period of time is 77 percent, almost 10 percent lower than the undergrad rate.

Despite the promising rates over the last five years, the creation of Krawczyk’s position suggests there is much room for improvement. When compared to its peer institutions, Seattle U still has work to do where retention is concerned.

Seattle U’s 86 percent retention rate for the 2012-2013 academic year was lower than the freshman retention rates of its peer institutions Gonzaga University, the University of Washington, Santa Clara University and Loyola Marymount University. Gonzaga boasted the highest rate at 95 percent, followed by UW, SCU and LMU at 94, 93.2, and 92 percent respectively. However, the University of San Francisco, another of Seattle U’s peer institutions, lagged slightly behind Seattle U at 84.8 percent.

From a national perspective, all of these universities have had spectacular retention rates. Prior to the economic downturn, the average national retention rate for private, four-year universities was just 74.8 percent. Then, in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis, that rate fell to 71.5 percent. By 2010, the rate had returned to 74.8 percent and is currently trending upward at a gradual pace.

Although the university has an understanding of the number of students who leave the school on a yearly basis, it has yet to accumulate significant data that explains why students leave. Krawczyk and the university are now in the process of collecting this information. There will be a new survey given to students who depart so that the school can better track the reasons why students leave Seattle U. Using this data, the school will be able to make decisions on how to improve retention rates by further supporting its students.

Even without this data, Krawczyk knows of several reasons why most students leave Seattle U. The biggest reason is financial.

“I left Seattle University because it was getting expensive for my mom to pay for me and my sister since we were both going to be at private universities, so I chose to stay home,” said former student Zachary Carias, who left the school in 2013.

For most students, the decision to leave doesn’t come down to just one reason, but a combination.

“Seattle University is not inexpensive,” Krawczyk said. “Money almost always comes up. The main reasons are money, the weather, missing family and friends, and not making the connections that you wanted to make.”

Another former student, Anya Rehon, shared that she was not satisfied with the opportunities presented to her at Seattle U. She also blamed the climate.

“The weather is a reason too, but that’s not the university’s fault. That is Seattle’s fault,” said Rehon.

Aside from transferring, some students may decide that college in general isn’t right for them. Current freshman Max Magerkurth plans to leave the university because he feels like he doesn’t need a college education to be successful in his field. Magerkurth, who is interested in filmmaking, feels he can gain the knowledge necessary to pursue a career in the industry without a degree.

Seattle U has already taken several steps toward encouraging students like Carias, Rehon and Magerkurth to stay at the university. According to Krawczyk, the biggest step in improving the school’s retention rate has been purchasing a new retention software program called Starfish. Starfish will allow advisors to receive early alerts for students who may be having issues at the university that could lead them to transfer or drop out. The software is still in its implementation stage, but should be live by January.

“There are a lot of resources for student situations and what is being done to support the student,” said Krawczyk. “Starfish will allow us to centralize those issues. It will give us the ability to have academic advisement software, student planning documents, grad checks, and online scheduling on one channel.”

Like Meyers, one issue that many students face during their first year at any university is trying to fit in. As a freshman or transfer student, coming into a new environment that’s filled with new people can be challenging. This problem is combatted at Seattle U by several programs like Welcome Week and social events put on by various organizations. One type of program that some believe has been particularly effective is mentorships. The International Student Center, the Office of Multicultural Affairs, the Albers School of Business and Economics, and even a few clubs offer such programs.

“Having a connection with someone really helps with retention,” said International Student Center Graduate Assistant Luisa Lora. “You have someone to confide in, a confidant and a friend.”

The International Student Center houses a mentorship program called the Ibuddy program. Seattle U’s international students are paired up with either domestic students or other international students who have been at the university for a few years. The system is designed to help the student build an instant relationship with someone from the university who can help them adjust.

“The Ibuddy is there to allow the person to feel that they matter here, that they are a part of the community. They are another layer of support,” said Ryan Greene, director of the International Student Center.

The Office of Multicultural Affairs conducts their peer mentorship program through the Connections Leadership Immersion Program. The program, which is for first year or transfer students of color, is designed to help students “become committed, connected leaders of color who possess an awareness of self, group, and community, and who are empowered to effect sustainable change,” according to Juanita Jasso, the assistant director of OMA.

There are multiple mentorship programs offered in Albers, but only the New Student Mentor Program utilizes current students as mentors. In the program, junior and senior students mentor freshmen and transfer students throughout their first year at the university in hopes of encouraging retention, academic success and professional development.

Albers’ other programs are mentorships that mainly focus on professional careers and have been quite successful in retaining grad students.

“I think that the Albers mentor program has a big impact on the grad population. Some tell me they came because of the program. It was a deciding factor. They come out having great relationships. It was the highlight of their grad program,” said Megan Spaulding, the manager of experiential programs at the Albers Placement Center.

Several sources believe the mentorship programs offered at Seattle U have been effective in helping students adjust to college life and have made an impact on retention.

Whether it’s because of mentorship programs, the city of Seattle, or campus culture, it looks like Seattle U’s retention rate is in solid shape. With Krawczyk on board, it might even improve over the next academic year.

“When we talk about improving retention, we are not talking about fixing a problem, but rather trying to cross the goal line and be the best of the best,” Krawczyk said. “Having my position created is a testament that [Seattle University] wants to do right by its students.”

The editor may be reached at editor@su-spectator.com