“Women, men, girls and boys, it is time to be conscious!”

This is a call to action from “Muda Waka Sema,” the third installment of ART on the Frontline, an empowerment project produced by Seattle University’s Yole! Africa. Each musical episode gives the audience a look into a political or social concept.

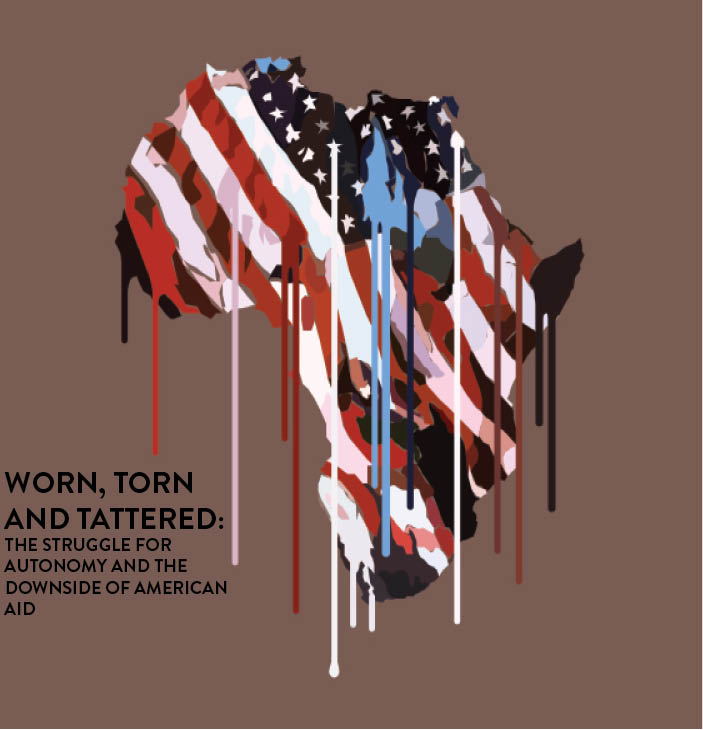

This time, they are calling for autonomy for Africa.

Yole! is an organization with a club branch at Seattle University led by student Allason Leitz, a Global African Studies minor. The club wants a new look at social justice—one that promotes the empowerment of communities.

Autonomy refers to the concept of self-governance and sustainability without dependence on outside sources.

There are areas of Africa in which the concept of autonomy is both a struggle and a goal. Several clubs and students at Seattle U are working to understand and visual a new way of seeing the world and the role of American aid in an international context.

Autonomy is complex, but it just has to be approached in the right way, said Seattle U student Joyce Keeley.

Keeley spent fall 2011 to spring 2012 in Tanzania learning Swahili. Initially, she was nervous about getting involved in international development because of the ethical and moral dilemmas at play.

“I had this thought in mind that Westerners have gotten involved too much already and they didn’t know what they were doing,” said Keeley. “In a lot of ways I think that is still true, but when I got there I would have friends and other students or colleagues who would say, ‘You know you have a computer and you won’t show us?’ or ‘You know how to speak English and you’re not teaching English?’ So, all these skills that I didn’t think I had and they felt I should share.”

This supports the idea that aid and education are needed, but the question is how and how much.

Dem. Rep. of the Congo

SU’s Yole! Africa club has forged a connection with the village of Isangi which is working to achieve autonomy.

Leitz’s club, Yole!, has forged a special connection with the village of Isangi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is one location struggling with cultural, political and social independence. The Yole! club is one of several on campus working to find the fine line between American aid and African autonomy.

“Yole” means “to come together,” a sentiment echoed last Wednesday night when the Yole! club sponsored a film screening and conversation on campus discussing the complexities of autonomy.

The movie introduced the village of Isangi where the community is trying to facilitate its own autonomy—it doesn’t want to depend on foreign aid or outside organizations to function at a minimal level.

In working toward this goal, they are met with the challenges around foreign aid such as how unsustainable and controlling foreign help can be in Africa.

A conversation following the film was led by Samuel Yagase, the 1992 founder of GOVA (Groupement Des Organisations Villageoises d’Auto-Developpement), a non-governmental organization (NGO) promoting self-reliance based in Isangi.

GOVA collects donations from residents to pay for community needs. It recognizes that to have an impact on local efforts, it must rely on its

own success.

One of their most utilized tools is the radio—it is their most consistent form of communication with the world outside of Isangi. Within the community, the radio is used to guarantee transparency regarding GOVA’s funding.

Every time a community member or outside source donates, the source and amount is announced over the radio. The shared belief is that no one will try dipping into the funds if the entire community knows how much money should be there.

Too often, money is given to an organization, and then forgotten about. But people need to pay more attention to where that money is or is not ending up, said Director of the International Student Center, Ryan Greene.

“When you think of agencies like the U.S. Agency for International Development, most people know that six cents of the dollar generally makes it to the people on the ground,” Greene said. “That means 94 percent is used for something else and it’s usually used for administrative overhead.” While providing aid can be a good thing, people need to look deeper at these organizations and their goals which can ultimately have a negative effect on a community.

Ghana

One of the many countries that receives loans from the World Bank under conditions outlined by structural adjustment programs.

One example Greene used is The World Bank. The bank attaches policies called Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) to loans for respective countries—these programs dictate the conditions for receiving aid from the bank. Most research says loans for African countries have twice as many Structural Adjustment Programs than other parts of the world.

These programs and loans alter the economy and open general agreements on trade and service. In Ghana, for instance, one of the Structural Adjustment Programs attached to the loan required students to be taught in English.

“I don’t think getting rid of a language or several languages is a good idea for a culture,” Greene said. “I think some of the SAPs attached to some of the African aid are really a detriment to Africa. From an international education perspective that is upsetting to hear.”

If aid is coming from an international source, the organziation has the ability to say where that aid goes, thus limiting the flexibility of the country to use the aid for their other purposes. In addition, Yagase said, NGOs are not always knowledgeable about the best way to help other countries. Many foreign aid organizations fail–the incoming aid and the need of the country are often two very different things.

“It’s become such a fad now,” said Leitz in reference to the image of international organizations interacting with locals. Westerners working alongside Africans is a picture that is capitalized to the extreme, she said. Sooner or later, America has to step back.

It’s kind of like the family, Yagase said last Wednesday.

A parent spends their whole life providing their child with education and resources. At some point though, the child needs to learn to provide for him or herself. If the child spends their whole life depending on others to survive, the child’s future and successes are limited.

In a similar way, NGOs from all over the world can pour aid into Africa, but eventually, these places have to be self-sustainable in order to be successful, Yagase said. Oftentimes communities even have to turn away money in order to maintain their autonomy, he said.

Yagase wants to be clear that GOVA does not discourage monetary donations from other countries, though. He does, however, stress the importance of making a connection with the area.

Seattle University student Tesi Uwibambe, originally from Uganda, is an example of someone aiding in a community she knows a lot about. In 2008, when Uwibambe was in the 9th grade in Uganda, there were incidents of child sacrifice where children where found dead or mutilated. She and a group of friends were motivated to take action.

“We talked to our art teacher and he had a really crappy car that he let us paint,” said Uwibambe. “We hung the slogan ‘Stop Child Sacrifice’ on the sides and hood of the car. One of the girls had the idea to have people sign it and then prominent people such as musicians, entertainers, politicians, and eventually it reached the chief of police of the country and ultimately the first lady signed it.”

Uganda

Promoting local activism in herhome country of Uganda, student Tesi Uwibambe was instrumental in the passage of anti-child sacrifice legislation.

The groups got legislation and petitions together to give this bill to end child sacrifice in Uganda. Earlier this year, after four years since Uwibambe began her efforts, a law passed and since then there has been a specific task force against child trafficking and child sacrifice, but witch doctors are still an issue.

“There are witch doctors that deal with black magic and child sacrifice” Uwibambe said. “They tell people they need to kill children for their own needs; that’s one part of the law we are working on, which is a little political because people are scared to have their beliefs threatened.” Uwibambe plans to continue this movement.

“It’s pretty incredible to see the impact [Seattle University students] have had,” Greene said. “There are people who are politically affiliated that can’t get some of this work done, yet here they are as students really making great progress and helping support society.”

In hopes of continuing to inspire a redefined view of social justice based on autonomy, students at Seattle U are dedicated to educating themselves first, and helping second.

Seattle U’s chapter of Global Public Health Brigades puts together mission trips to Honduras, Panama and Ghana. They approach their trips with a holistic approach to aid.

“We don’t have the ‘one-solution fits all’ mentality,” said David Renteria, president of the Seattle U chapter. They understand that issues in Ghana aren’t going to be the same as in Honduras. That’s why they have divisible programs that address different issues, such as micro-finance, architecture, water and public health.

“Global Brigades is a non-profit that takes a holistic approach in order to develop sustainable and context-based solutions for under-served and impoverished communities,” Renteria said, adding that simple handouts will not suffice.

Seattle U’s African Student Alliance (ASA) club explores a different factor in the issue of autonomy. They focus on the cultural side of Africa in an attempt to counteract the poverty-stricken image of the continent that is most prominently broadcast.

“Our club supports the autonomy of African countries through our focus on and celebration of traditional and contemporary Africa and its various cultures,” said ASA co-president Jessica Gomez. In this way, they hope to nourish an aspect of the continent that is not defined through degrees of dependence on the rest of the world.

The editor may be reached at news@su-spectator.com