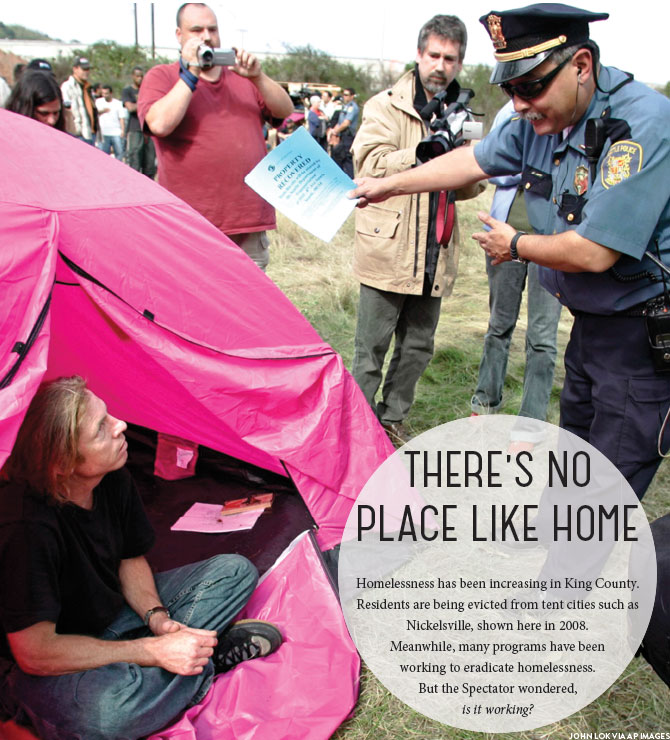

Homelessness has been increasing in King County. Residents are being evicted from tent cities such as Nickelsville, shown here in 2008. Meanwhile, many programs have been working to eradicate homelessness. But The Spectator wondered, is it working?

Is Living in America Hopeless for Homeless?

Alaina Bever

Staff Writer

As Seattle gears up for another mayoral election, many questions weigh on voters’ minds as they consider how

to vote.

Education, minimum wage, and transportation are just a few of the most important issues to Seattle voters. But one issue that many Seattleites have forgotten in recent years is a problem that has by no means disappeared: homelessness.

In spite of efforts from private and public organizations to provide shelter and support for Seattle’s homeless, statistics show that homelessness rates in Seattle are actually increasing.

An organization called the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness conducted a “One Night Count,” in which 800 volunteers counted people living on the streets of King County during one night.

The 2013 results, according to the Coalition’s website, counted 2,736 men, women and children without shelter; a 5 percent increase from the 2012 count.

As the city and the nation draw closer to the U.S. government’s 2015 goal for eradicating homelessness, it’s time for a much needed evaluation of this crisis and whether or not the current programs are designed for success.

According to a 2012 assessment by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the level of homelessness stayed consistent from 2011 to 2012, but with numbers of homeless families increasing while the number of homeless

individuals decreased.

Given the amount of time and effort put into ending homelessness across the nation, this statistic is not promising.

However, stagnant national homelessness rates might not be as distressing when considered with other factors.

For example, it can be considered a mark of the successful programs that homelessness did not increase during the economic recession, as would have been expected. According to the Census Bureau as reported in the New York Times, the poverty rate in America was 22 percent higher in 2012, near the end of the economic crisis, than in 2007 when the struggles in the economy began.

For a time, homelessness was actually significantly decreasing across America, according to an August article in the Atlantic. The National Alliance to End Homelessness estimated a 17 percent decrease in total homelessness since 2005.

But, they reported, that number is not likely to last under the looming program budget cuts.

In the work to eradicate homelessness, though, communities aren’t focused so much on those numbers.

The bulk of national efforts are aimed at creating affordable housing and assisting Americans with finding and retaining housing.

There is more work to be done, though, if the nation hopes to reach its goals in the coming years. The U.S. Acting Assistant Housing Secretary for Community Planning and Development, Mark Johnston, was quoted in the New York Times for his estimate that preventing homelessness in the U.S. requires a budget of about $20 billion, which is much higher than the 2012 budget of $1.9 billion.

Until the U.S. government can come up with either a more efficient solution or the funding to make the current plan work, the nation will rely on local government and private organizations to aid in the effort to end homelessness.

Homelessness in Seattle has often been noticeable due to the many makeshift living spaces around King County in 2008, known to many as a tent city or ‘Nickelsville’ after former Seattle mayor Greg Nickels.

According to a recent article by the Seattle Times, over 275 people were living in these tents in June 2013.

This summer, however, the Seattle City Council decided that the encampment had to be shut down and voted down a proposal to add city and private land to the areas where tent encampments are allowed.

Residents of Nickelsville were evicted on September 1, but the shutdown did little to solve the homelessness crisis. Reports that new camps have been set up in different neighborhoods of King County demonstrate the need for affordable housing, and soon.

Until then, the homeless will set up camp wherever they can. Currently, land owned by faith communities are the only legal places for the homeless to camp out, but campers continue to set up illegal tents and move constantly to avoid eviction, according to many news reports since the Sept. 1 eviction.

These events have not stopped people from continuing to work to combat homelessness.

Here in Seattle, progress to combat homelessness has been made possible by the efforts of the Committee to End Homelessness (CEH). The CEH is an association made up of advocates from the government, non-profits, and faith-based organizations. According to the CEH website, their goal is to prevent homelessness by building political support, increasing the efficiency of current resource use, and reporting these outcomes to the public.

In order to combat the issue of homelessness, the CEH created a “Ten-Year Plan” that consists of building housing units for homeless households, providing health care and mental health services, and working with jail and substance abuse programs to ensure better support upon discharge.

A major emphasis of the project is reporting progress to the public.

The CEH is closely related to Seattle University; President Fr. Stephen Sundborg, S.J., is on the Governing Board and Lisa Gustaveson, Manager of the Seattle U Faith and Family Homelessness Program, helped draft the original ten-year plan.

According to Gustaveson, things have changed since the time that the plan was written. Although the CEH has made progress with building new housing units, much of this success was obscured by the growing homelessness rates due to the recession.

“The ten-year plan has been a good guide for the community,” Gustaveson said. “So really that’s what the plan is, it’s a guide for the community to make decisions about how to spend. It’s hard because when we wrote the plan, we were in a certain economic situation, things were going really well, and I think that it’s really important that we emphasize that there have been significant changes.”

According to Gustaveson, a huge part of eradicating homelessness is preventing families from becoming homeless in the first place. Once a family loses their home, they become part of a cycle that is hard to break.

While the construction of more low-cost housing has been a major success of the past decade, the cities homeless count has continued to rise. Without constant support and determination, statistics show that the effort to end homelessness may not reach its goal by 2015.

Alaina may be reached at abever@su-spectator.com

SU MIXES FAITH, FILM AND FAMILY

Darlene Graham

Volunteer Writer

One out of every 38 children in Washington state is affected by homelessness, according to Seattle University’s Faith and Family Homelessness project blog. That number adds up to over 27,000 children and families living in poverty in this state alone.

Two years ago, during the economic crisis, Seattle saw an ever-increasing shortage of affordable housing and a low living wage in Washington state, making the issue of family homelessness more grave.

Recognizing a need for action, Seattle U’s School of Theology and Ministry launched the Faith & Family Homelessness Project (FFH Project) with the mission of providing leadership and education to local faith communities in order to foster partnerships dedicated to ending the cycle of family homelessness.

The FFH Project addresses the Puget Sound area by incorporating a variety of 14 religious and secular congregations in King, Pierce and Snohomish counties. The congregations range from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community to the Puyallup Church of the Nazarene.

Program manager Lisa Gustaveson highlighted the importance of relationships in furthering the mission of this project. Those in more fortunate circumstances can never truly understand the mentality of homelessness, she says, but as persons of faith, be they humanist or Mormon, imagining the imminence of this reality for themselves is essential.

The Faith & Family Homelessness Project is one of the three different departments at Seattle U committed to ending family homelessness.

According to their website, the university’s Center for Strategic Communications received a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation of $250,000 to support their latest project, the Film & Family Homelessness Project. This project will support four filmmakers from the Seattle area in developing films to depict the story of Washington families enduring homelessness and poverty.

The screening of these films will begin in winter 2013 with hopes of them being featured in the Seattle International Film Festival.

In addition to the Film & Family Homelessness Project, the Center for Strategic Communications also works to increase public awareness about the specific causes of and solutions to homelessness with the Project on Family Homelessness.

Originally titled the Journalism Fellowships on Family Homeless when it was established in 2009, the project was first a fellowship program supporting journalists in their work of multimedia reporting and strategy formulation for homelessness prevention.

Also funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the project is dedicated to supporting Washington nonprofit organizations and the other Seattle U departments committed to ending family homelessness, according to program manager for the Film & Family Homelessness Project Lindy Boustedt.

Most recently, Seattle U’s three family homelessness prevention projects united with the Seattle Art Museum and Sanctuary Art Center to host the sold-out screening of the Academy Award-Winning documentary-short “Inocente.” The film tells the story of Inocente Izucar’s experience with homelessness.

Now 19, she uses artistic media to talk about her past; her paintings are in high demand nationwide.

Events such as this are put on through the different Seattle U homelessness projects in order to encourage students to learn more about these issues.

“Not here to lecture you, but to enlighten you,” Boustedt said of Izucar’s film.

Editor may be reached at news@su-spectator.com