During the first quarter of her freshman year at Seattle University, Lindsey was raped.

Lindsey (not her real name) had been texting and flirting with a “friend of a friend” one night while he was at a party. They agreed that they would hang out later that night and by the time he arrived at Lindsey’s dorm room, he was intoxicated.

He started kissing her and ignored her verbal and physical hesitation. She turned her body away from him and eventually backed herself into a corner, but he still advanced.

“[I kept] trying to say ‘I don’t think this is a good idea, I don’t think we should be doing this, I don’t know if I want to do this,’ repeating over and over. At a certain point, it was like he really wasn’t listening to anything I was saying so I just zoned out,” said Lindsey.

As the frequently referenced statistic goes, one in every four women will be raped while in college. Lindsey was the one.

Washington state defines sexual intercourse as occurring “upon any penetration, however slight.” Lindsey claims that by these standards, she was raped. The assault likely would have progressed if her roommate hadn’t walked in, at which point Lindsey’s aggressor stopped and eventually left the room.

“I had watched TV shows or seen movies and seen a situation where the person kind of blows it off and goes ‘Oh, it wasn’t that big of a deal. It was fine. I’m fine.’ I definitely caught myself doing that that night,” Lindsey said of her decision to report the offense. “[Then I] was like, ‘Wait a minute…I said that if this ever happened to me that I would report it.’ So I did.”

The report made its way to the Conduct Review Board. The conduct process culminated in a hearing that was held two and a half to three weeks after the assault itself.

Although Lindsey does not regret her decision to report the incident, she was worried that her report would ruin her aggressor’s life. After the Review Board found her aggressor to be responsible, he was suspended from the university. He has not returned.

“To point to a person and say, ‘This is what you did. You are a bad person because of it,’ is missing a lot of things,” Lindsey said of her feelings toward her aggressor. “I don’t think that he is a bad person. I think he made a really bad choice and I try to think of where those choices come from.”

Most people—victims, aggressors and those untouched by sexual offense—don’t wonder about the reasons for sexual offense in the same way that Lindsey does. Most vilify and blame. Those who don’t take sides sweep the phenomenon under the rug entirely. Ashamed and uncomfortable, few say the things that need to be said.

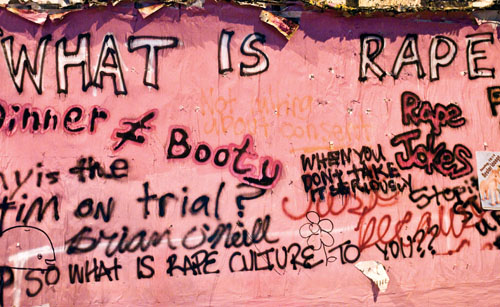

“What is it in our culture, what is it in our society, that is making those things happen so frequently?” Lindsey said.

Lindsey’s sexual offense case is one of two cases known to have taken place at Seattle U last academic year. These cases, as well as changes made to the university’s conduct process and Code of Conduct this fall, have raised questions about the perception and handling of sexual offense in today’s society, particularly on college campuses. Although reported sexual offense cases are fewer at Seattle U than most universities, increased discussion that critically and unabashedly examines the topic’s complexity is essential in developing healthy social attitudes toward sex and proper handling of such cases.

THE NEW CODE AND THE SEXUAL OFFENSE REVIEW BOARD

Earlier this month, the Seattle U Code of Conduct was altered to include a more comprehensive explanation of how the school handles sexual offense cases. The updated Code, as well as the creation of a new Conduct Review Board, was triggered by a document from the U.S. Department of Education called the Dear Colleague letter, which the school received on April 4, 2011. The Dear Colleague Letter—last sent to universities in 1997—essentially suggested that American universities reevaluate and improve the process through which sexual offense hearings are handled.

“Seattle U takes the recommendation seriously so we’ve revised a policy that really takes into consideration the best policies in the nation,” said Darrell Goodwin, associate dean of students.

Goodwin hopes that more students will feel comfortable coming forward with reports of sexual offense now that the Code is more explicit.

The updated Code of Conduct includes Seattle U’s definition of consent, a list of guidelines designed to help students steer clear of situations in which a sexual offense could occur, reporting procedures and an overview of the student conduct process.

The key change made to the university’s conduct process is the official implementation of the Sexual Offense Review Board (SORB) this academic year.

“Prior to the Dear Colleague letter, cases would’ve been handled by the Conduct Review Board. [After] the Dear Colleague Letter, Seattle U proactively responded to putting some of these things in place and now they’re being institutionalized in the form of a document this academic year,” Goodwin said.

According to SORB member and campus minister Marilyn Nash, the job of the SORB is to “determine responsibility for breaches in the Code of Conduct” related to sexual offense. After Public Safety investigations have taken place, facts are gathered and definitions are reviewed, the board’s final decision as to whether the accused is responsible or not serves as a “recommending voice” in the sanction process. The SORB is not the final determining factor in the sanction process.

SORB members undergo a training process that includes the standard conduct review training, but goes further to include an intensive briefing on sexual offense specifically. According to Nash, this sexual offense-focused training includes the examination of “factual” and legal definitions of freely given consent and intentionality.

“Being a part of any review board, but particularly a sexual offense review board, is challenging and to know that you can trust the process because it is a facts-based process…helps us to be really clear,” Nash said.

Although members of Seattle U’s Conduct Review Board and SORB are typically confidential, Nash agreed to speak with The Spectator and was the only board member interviewed for this story. Nash believes that the names of members are not published because it better establishes a clear commitment to confidentiality.

CONSENT AND ALCOHOL

According to the Code of Conduct, Seattle U “will not recognize consent if the complainant is unconscious, frightened, physically or psychologically pressured or forced, intimidated, impaired because of a psychological condition, or intoxicated and/or impaired by use of drugs or alcohol.” This definition of consent is not necessarily new to the university, but this is the first time it has been included in the Code of Conduct.

The intoxication clause—a vital component of legal consent definitions since the creation and rise of Rohypnol, better known as the date rape drug, in the 1970s and 1980s—poses particular concerns. While standards involving intoxication and impairment must be established in order to protect potential victims and potential aggressors, the finality of the clause seems slippery in an environment where sexual exploration, immaturity and impulsiveness run rampant due to age and college culture.

According to Public Safety Director Mike Sletten, most sexual offense cases at Seattle U occur between acquaintances in a context that involves “social drinking.” Many Seattle U students also find this to be true.

Based solely on the Code of Conduct’s definition of consent, it seems that any sexual offense case brought before the SORB that involves alcohol and proof that a sexual encounter of any kind occurred would result in sanctions against the accused, whether or not coercion had occurred.

For example: two people—friends or acquaintances—are equally drunk when they leave a party in search of a more private spot. Consent is given, or appears to be given, by both people. One partner retracts his or her consent once sober after the sexual act has already occurred. Is the other partner a rapist?

“We’re telling you a person who is intoxicated cannot give consent. We will not recognize it,” Goodwin said.

The clause seems to remove any and all sexual responsibility where drinking is involved. The idea that drunken actions are products of sober thoughts applies to the intentionality of the accused, but not the complainant.

“If you both were drunk and neither of you were influenced by any sort of drug [given] by [another] person, then I don’t think it’s sexual offense,” an anonymous female student said. “You can’t just blame it on alcohol. Alcohol is not you. It’s something you decided to take to influence your decisions.”

It also would appear that some sexually active students use alcohol or drugs as a means of having enjoyable sex.

“Some people I’ve met will only have sex when they’re drunk…because they’re not comfortable enough with themselves and with their bodies and with sex to just talk about it and be relaxed about it,” said sophomore Gordon Scholl. “A lot of people feel they need [alcohol] as a crutch to help them get where they want to be sexually.”

For that very reason, Nash finds that the refusal to recognize consent in cases where alcohol and drugs are involved is the key to promoting responsible, mature and healthy sex at Seattle U. Nash worries that students do not prioritize “giving or receiving” consent.

“The culture at many universities is a hook-up culture that often includes alcohol. This means that clear, asked-for consent, is more important in that culture,” Nash said. “We are talking about very adult behavior, so it calls for very adult interactions.”

Despite the seemingly black-and-white nature of the clause, Goodwin insists that an alleged aggressor will never be held automatically responsible in situations involving intoxication or impairment because the school’s review process is “hyper-dynamic.”

VICTIM FAVOR

Beginning with the Feminist Movement and gaining momentum with the Victim’s Rights Movement, there has been a distinct historical shift away from aggressor-favor to victim-favor in the past few decades. This shift can be seen in the policy of many universities and other institutions, although the criminal justice system continues to victim blame according to many women’s rights and victim’s rights advocates.

Victim blame has been a contentious issue—most famously embodied by the SlutWalk protests—since 2011 when Toronto constable Michael Sanguinetti told females to “avoid dressing like sluts” in order to avoid rape. In general, the perception of consensual sexual activity has come to exclude silence. Meanwhile, sex offenders have become perhaps the most vilified criminals in society.

According to Jacqueline Helfgott, chair of Seattle U’s Criminal Justice Department, many of the “Draconian, really punitive policies” that have been put into place in Washington state—including the Community Protection Act of 1990, the Two Strikes Policy of 1996 and Determinate Plus Sentencing—trap sex offenders within the justice system “indefinitely.” Helfgott thinks that the severity of these laws and the size of this legal “umbrella” is driven by America’s Puritan ethic. Because “normal” sexual interaction makes society squirm, sexual deviance of any kind is difficult to understand and discuss.

On college campuses, definitions of consent in general have shifted toward a condemnation of the “deviant” as well. This pro-victim bias, while necessary, could create a borderline “guilty until proven innocent” standard for alleged aggressors.

“I think it is an equalizing shift if you look historically at it. On a personal level, it is a dangerous shift when you look at possibilities for wrongful conviction,” Helfgott said.

When it comes to acquaintance rape cases, which are founded primarily on “he said, she said” evidence and often lack a witness, accusations of sexual offense could lead to possibly unwarranted consequences for the accused. The alternative, however, is also harrowing.

On Oct. 17, the Amherst College student newspaper published former student Angie Epifano’s first-person account of acquaintance rape at the university. Epifano told a counselor about her assault a year after it occurred and the school shrugged off her report:

“They told me: We can report your rape as a statistic, you know for records, but I don’t recommend that you go through a disciplinary hearing. It would be you, a faculty adviser of your choice, him, and a faculty advisor of his choice in a room where you would be trying to prove that he raped you. You have no physical evidence, it wouldn’t get you very far to do this,” Epifano wrote.

The school eventually admitted Epifano to a psychiatric ward and tried to stop her from returning to Amherst following her release. Epifano finally withdrew from the university while her rapist, whom she eventually accused, “graduated with honors.”

In light of stories like Epifano’s in which the victim is ignored or dismissed, Seattle U’s choice to favor the victim could be a positive legal development.

“On a policy level, a legal level, [the Code] trusts the victim… As a cultural shift I think that’s really important. It’s important that the victim is trusted,” Helfgott said.

GENDER

“Statistically, the reality of the situation is that most sexual crimes are committed by men. They can be committed by men against women, men against men, but most of them are committed by men,” Helfgott said.

According to Sletten, Public Safety has seen reports and inquiries of all gender combinations, but the male aggressor and female victim scenario is by far the most common.

Although sexual offense is not necessarily an inherently gendered crime, Helfgott believes that society has made it so via centuries of behavioral socialization.

“Aggression is socialized out of girls and into boys, especially sexual aggression… The result of that is boys and men get to own aggression as a survival tool and girls and women do not,” Helfgott said.

Even post-Feminism, society still perceives sex crime as occurring between a male aggressor and a female victim. Helfgott attributes this to a popular culture that over-sexualizes women and has created a victimized female archetype upon which society is fixated. On television and in movies, “images of women being eviscerated, having their boobs cut off and [being] sexually mutilated” are common, whereas this kind of violence directed at a male victim is rarely depicted.

The most notorious example of female sexual aggression is the 1993 Lorena Bobbitt case. Lorena Bobbitt, a victim of domestic abuse, cut off her husband’s penis and threw it out of her car window. John Bobbitt’s penis was later reattached and he went on to become a porn star.

The Bobbitt case proved publicly that males could also be sexually offended, by females or by other males, and the thought created “hysteria.” Although the Bobbitt case broke through almost 20 years ago—and according to Helfgott, two of the sexually violent predators in Washington state have been women—sexual offense against men is still largely unrecognized and underreported.

An anonymous male student at Seattle U recounted an instance in which a female friend grabbed him at a party and initiated unwanted sexual activity: “I just…let her do her thing until she had to leave. I felt like crap the entire time and I felt used… It was definitely social pressure that kept me from stopping it… I just kind of disconnected myself from my body and let it happen.”

According to various male sources at Seattle U, most men feel as pressured to have sex as women feel pressured not to have it. Most of those interviewed cited emasculation as the primary reason why men sometimes don’t say no. When they do say no, it is left behind closed doors.

“I think most guys definitely have [felt violated] but they would never admit it,” Scholl said.

Every male student interviewed said that his female partners rarely ask him for consent.

While men can sometimes feel like victims, they more often recognize their positions as potential aggressors. The expectation that men should initiate sex is what often labels the male as the dominant sexual partner and the female as the submissive.

“I think that men are more vulnerable to [sexual offense] charges because they are expected to make the first move,” said one male student.

The worry surrounding this gendered perception of sexual offense is that policies target males and categorize them as the “bad guys.”

“Coming from an African-American culture, the power of language and the power of accusation has put many African-American men at risk. Some of them are dead,” said Director of Women and Gender Studies Mary-Antoinette Smith, citing the murder of Emmett Till.

Goodwin, however, believes that the school’s handling sexual offense is gender neutral.

“Some people are concerned that these new consent policies are just there to entrap guys…but it’s actually a comprehensive process that really tries to care for all of our students,” Goodwin said.

Many social theorists—including activist Jaclyn Friedman, author of “Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape”—believe that women are in the midst of an awkward sexual transition: as the female demographic heads toward sexual empowerment and satisfaction, it continues to “back step” because of over-victimization.

Friedman argues that messages like “no means no” continue to promote abstinence and the rejection of sex amongst women rather than encouraging them to have pleasurable sex. Essentially, society empowers women to choose not to have sex, but it doesn’t empower them to choose to have it. Thus, the choice to have sex, particularly casual sex, is still considered to be shameful or harmful. It could be that society has turned to reactive accusations of rape and an obsession with victim blaming because proactive sexual decision-making and assertiveness amongst women is still not fully accepted.

“I am really sexually confident…and if other people were sexually confident, they wouldn’t judge…but people judge so much,” one female student said of how fellow students perceive her sexuality.

MUTUAL RESPONSIBILITY AND THE PURSUIT OF EQUITY

When society denies the concept of mutual responsibility in “normal” sexual encounters, and, in some cases, acquaintance rape situations, society fails to look at sexual offense critically. Instead, it demonizes the aggressor or blames the victim. When this knee jerk bias becomes the basis upon which sexual offense is handled on college campuses and beyond, rape as a phenomenon is propagated, not stifled.

“Here in the States, we don’t talk about sex,” Smith said. “It’s something that is behind closed doors and we’ve always been nervous about sex, sexuality, even in our visuals on television. In Europe they’ve always shown the body, full representations of the body, equitably. Not just women, but men as well.”

How can a society that views the naked body as inappropriate view sexual offense in a critical way? When society cannot discuss the nuances of traditional sex, society certainly can’t discuss the nuances of bad, unhealthy or unwanted sex.

Mutual responsibility is still misunderstood because the concept asks for clear communication.

“Communication is something there’s not enough of. Our culture revolves so much around sex but when it comes to two physical people having sex, it is very taboo,” Lindsey said. “People have sex and don’t talk about sex. I think that’s a scary thing.”

Society is quick to victim-blame, quick to accuse someone of victim blaming, and quick to condemn an accused aggressor because blame is a response to discomfort.

Blame is an emotional, knee jerk reaction to what society doesn’t understand.

Despite the complexity of sexual offense, Seattle U seeks to handle what seems to be an unanswerable topic with a definitive lens. Both Goodwin and Nash assert that the SORB refers to “factual” definitions and legal standards when evaluating any given sexual offense case at the university.

“[I] feel that [I am] able to be objective in a very subjective situation,” Nash said of her SORB training and the board’s process.

The key to what makes the school’s handling of sexual offense “fair” ultimately lies in human nature. If members can review sexual offense cases at the university in a critical, unbiased and communicative way, then the creation of the board is a progressive step for Seattle U.

“In general, I have amazing colleagues. The people who are involved in the Conduct Review Board, including the [SORB], are amazingly well-intentioned people… The training for it and process for it is impressively equitable to me,” Nash said.

Although the measure is a commendable one, the school’s experience with sexual offense is still limited. Cases are rare and, therefore, not often dealt with by the university and the new process is in its infancy.

“The most frustrating thing [about the process] was the communication. It was two and a half to three weeks after the assault that the hearing happened and I wasn’t really informed of what was actually happening during any of that time,” Lindsey said. “I didn’t know if he was still on campus. I had no idea what was going on: When is this hearing happening? Is it happening?”

Although Lindsey called the school’s process “great,” the lack of communication left her feeling like she had to “advocate for herself.” But unlike Epifano’s experience at Amherst, Lindsey found that there were many resources available to her beyond the conduct process. She turned to Counseling and Psychological Services, participated in consent-positive events like the Peer Health Action Team’s “Take Back the Night” and moved on with her life.

Now, unlike much of the rest of the world, she is not afraid to talk about sexual offense. And it appears that, with all its kinks and contention, the school is trying to make the same leap. But it will take a lot more discussion to get there.