The Art of Jodhpur, India, Now at the Seattle Art Museum

JACQUELINE LEWIS • THE SPECTATOR

The Seattle Art Museum opens its newest exhibit, “Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts Jodhpur, India.”

For many of the objects on display at Seattle Art Museum’s (SAM) exhibition, “Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts Jodhpur, India,” it is their first time seen outside of the palace setting or on display in United States. Five centuries of visual art spanning from the northwestern state of Rajasthan out of the kingdom of Marwar-Jodhpur displays the relationship between patron, artist, expert, and public.

The exhibition tells the story of conquest, colonialism, and royalty through the historical and artistic narrative told by cross-cultural encounters and the evolving ruling class. While working on the project, SAM’s curator gained a different perspective on what “a ruler should be.”

“There were actually texts that gave instructions to rulers in this kingdom, they had to be a good role models, they had to be intellectually adept… they needed to be able to sing, they needed to be able to carry a conversation, and they needed to be patrons of the art,” Pam McClusky, SAM’s Curator of African and Oceanic Arts, said.

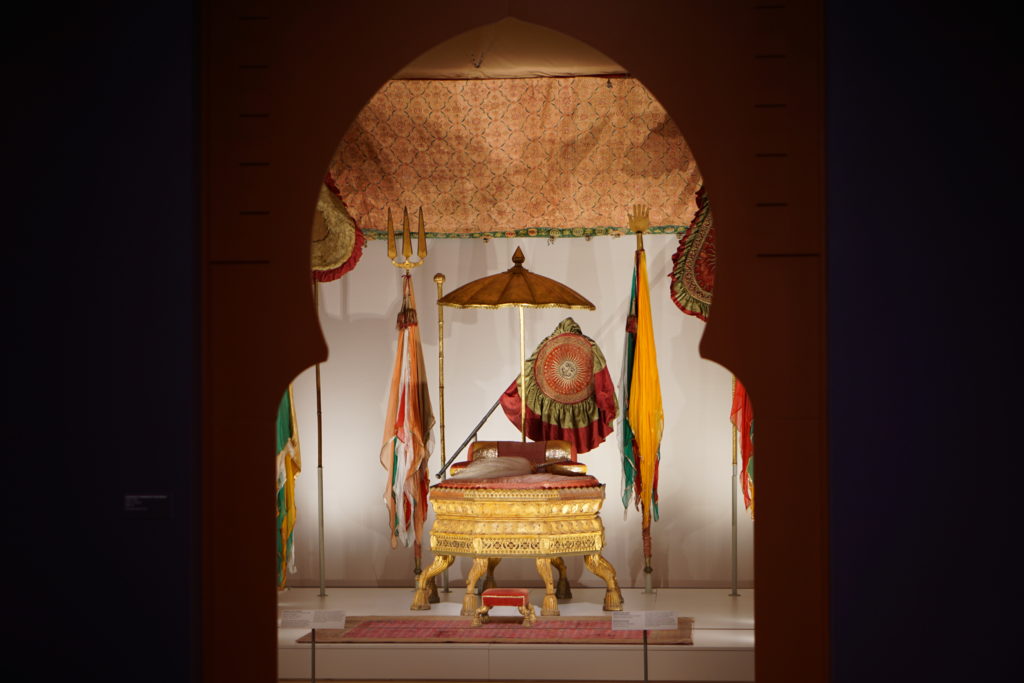

Woven canopies and textiles are a mark of the Mughal and Rathore styles. Singhasan with Chattr, or throne with parasol, is a mid-19th centurey piece associated with Rathores royalty, used in durbars, or royal receptions.

“[This] makes for a different notion of what it is to be a leader. We’re floundering in terms of how our leaders are being perceived or portrayed. Being a person that provides balance… and pleasure is actually an important part of human interaction… We lost a little bit of that.”

“The Peacock in the Desert” arrives at the SAM as the next stop on its national tour, having stopped at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston this past summer.

“The world is beyond the world we are living in.There is so much to learn and cherish in each of our worlds. We should continue with that rather than make opinions and being limited,” said Dr. Karni Singh Jasol, co-curator and director of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust.

“I am delighted that we are in Seattle where you have that spirit of diversity, that spirit of acceptance.”

The Mehrangarh Museum Trust, previously a historic fort, attracts visitors from all around the world to view the objects and attend concerts or festivals.

A photographic and video slideshow upon the exhibits fourth-floor entrance shows the Mehrangarh Museum space in the modern context, and Director Karni Singh Jasol oversees the exhibit alongside SAM staff.

The exhibition begins with Jodhpur during Rathores reign, which took place from the 13th century to the mid-20th century. The Rathores were taken over by the Mughal Empire in 1561 and they continued to share political and military alliances, as well as art, for the next three centuries.

Paintings of the court (and the women of the court) alongside the kings are displayed in dazzling closeness and on a large scale. The “La Dera” tent flanks an entire exhibition room and is the oldest and perhaps only Indian court tents in the world. In concern to Indian painting, they represent scene and portraiture that is unique from Western painting.

“If you looked at [an Indian] painting, it would be very confusing. It is new to you, it is not like Western art, these paintings were not meant to be hung like they were hung right now. They are meant to be held in your hand, as a part of storytelling. All of these paintings are a part of the large narrative tradition, a part of a storytelling tradition,” Jasol said.

In their original context, most of the paintings on display would have been brought out, held by a few people, and shared as a piece of a storybook. The painting would be taken away and the next artistic work, an installment in a story usually of mythology, history, or the cosmos, would be brought out as a continuing tradition.

Viewers can imitate this tradition by taking in the works at the minature level, with magnifying glasses perched on the wall for personal examination. On the other hand, guests can see the painting contextualized within other paintings from that period, located within a particular historical moment.

The exhibition ends with the Jodhpur’s dramatic transformation under the British Empire, showing a merge of garments, Western portraiture, and jewelry, showing a blended-imperial era known as the Raj. Their patronage, as well as the renovation of Umaid Bhawan Palace to a hotel operating today, is explored within the Maharajas of the past and future.

“India has the youngest population in the world, and here is art from that country which represents the continuing dynamic… it is not a culture of the past, it is a culture of the present,” Jasol said. “India is not a country frozen in time, it is dynamic, and it is contributing to the evolving world—whether it is technology, or the spiritual side of it with yoga —it is relevant. This art is relevant.”

Jacqueline may be reached at

jlewis@su-spectator.com